Crossing of the Savio River

After the capture of Rimini on Sept. 21, 1944, 1st Canadian Division was withdrawn into Eighth Army reserve to rest, reorganize and retrain while absorbing hundreds of replacements. Since Operation Olive, the battles for the Gothic Line began the division had suffered 2,511 battle casualties, including 626 killed in action. More than 1,000 other men had been evacuated as “sick,” including over 400 evacuated for “battle exhaustion.”

Psychiatric casualties had proved to be a major issue in all of the Allied armies, accounting for 20 to 25 per cent of casualties. The Canadians had long since determined that the large majority of men who broke under stress of battle could not be safely returned to combat units, so Special Employment Companies were created to provide a useful role in the rear areas.

The division’s rest period on the coast near Cattolica included opportunities to swim in the still-warm Adriatic and trips to Riccione or Florence. The leave centre in nearby Riccione was operated by the Salvation Army and was located in the Grand Hotel, “a first-class resort in peacetime.” Reserved for non-commissioned officers and ordinary soldiers, the hotel could accommodate 500 men in rooms with clean sheets and hot water. There were movies, army shows and dance music every night. The food was supplied by the army, but prepared and served by Italian chefs and waiters. Everyone in I Canadian Corps was eligible for a 48-hour pass to Riccione where, for a brief period, the war seemed to exist in a parallel universe.

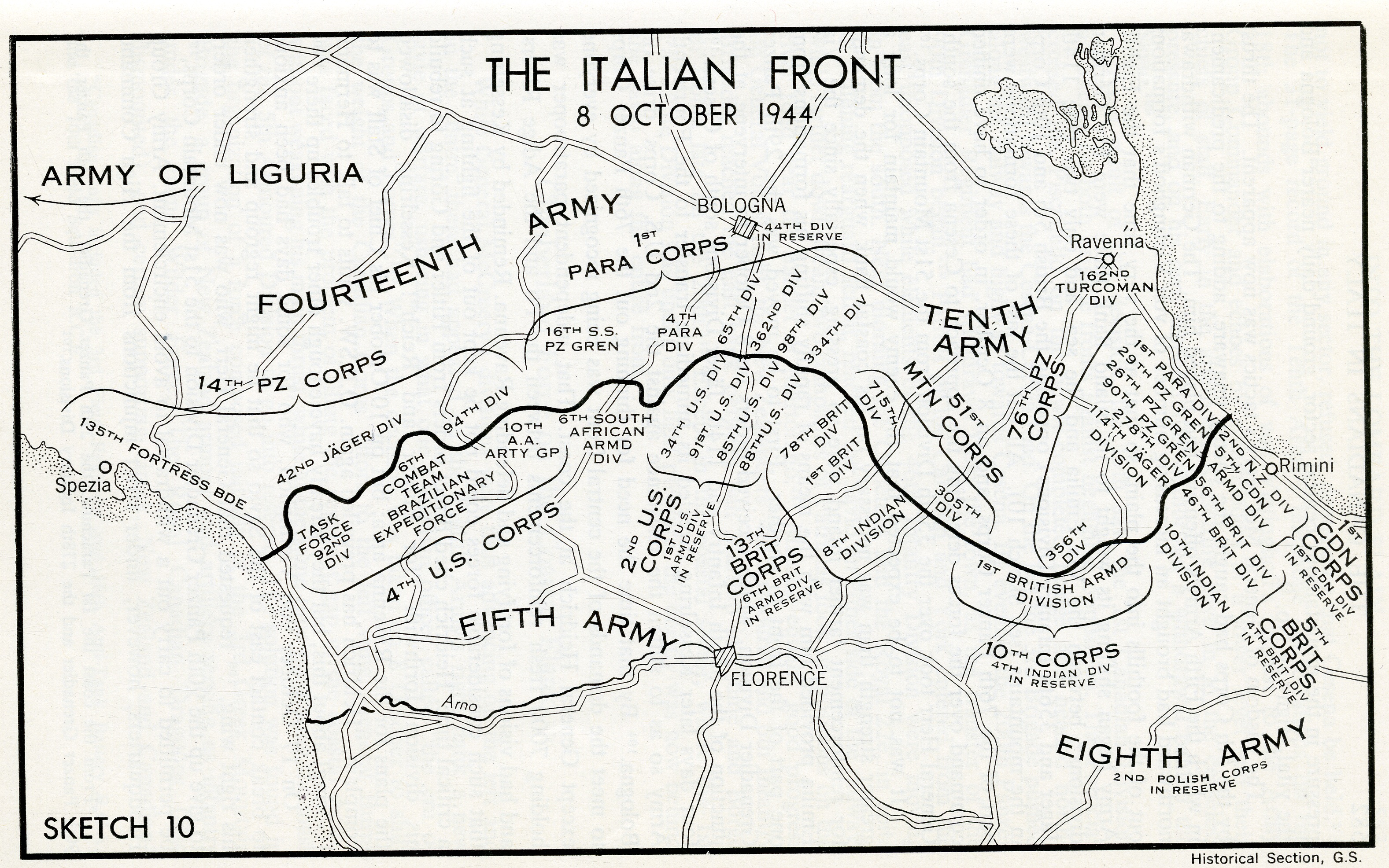

Hitler, however, was determined to defend Italy south of the Po River because the industrial production of northern Italy was needed and “another withdrawal might be too much of a shock for the German people.” Churchill, who had stopped in Rome en route to meet Stalin in Moscow, was determined to press forward in Italy and mount an amphibious assault across the Adriatic. Resources for such an adventure could only come from the Americans, but President Roosevelt refused to consider new initiatives in the Mediterranean. He told Churchill that “overshadowing all other military problems is the need for quick provision of fresh troops to reinforce Eisenhower in his battle to break into Germany and end the European War.” Neither Churchill nor General Alexander accepted this view and plans for a continued advance in Italy as well as a quick strike across the Adriatic were developed. Alexander ordered Eighth Army to continue operations to seize Ravenna while Fifth Army withdrew divisions into reserve until the weather improved and a new offensive could be mounted.

All of this meant that 1st Canadian Division’s rest period came to an abrupt end as the new commander of Eighth Army, Sir Richard McCreery, ordered the Canadians to relieve a British division taking over the advance to Cesena, using the Via Emilia, the main road between Ravenna and Bologna as their centre line. The New Zealand Div. was to advance to the Savio River on 1st Division’s right flank while V British Corps worked forward in the foothills of the Apennine Mountains.

General E.L.M. “Tommy” Burns met with his divisional commanders to explain McCreery’s plan. In his memoirs, titled General Mud, Burns recalled their reaction: “All divisional commanders pointed out the very bad going, and expressed the opinion that we might be drifting into carrying on an offensive in similar conditions to those of last autumn and winter where hard fighting and numerous casualties resulted in no great gain.”

Burns, who notoriously lacked any human touch in his relations with subordinates, won no friends when he replied curtly that “other troops in Italy and Northwest Europe were fighting under similar conditions and 1 Canadian Corps would have to do its share.” Despite this, Burns carried their protest to McCreery who reluctantly changed the plan to emphasize V British Corp’s advance in the foothills with the Canadian Corps providing support.

The protests of the divisional commanders reflected a crisis in morale that was affecting front line troops in both 5th and 8th Armies. The Canadians, short of trained reinforcements, were particularly bitter about the Zombies, those conscripted for service in Canada only. Farley Mowat, in his postwar history of the Hastings and Prince Edward Regiment, described “the growing disillusionment with all authority…beyond the regiment,” quoting the sardonic verses troops sang as they marched back into battle:

Six and twenty panther tanks

are waiting on the shore,

But Corps intelligence has sworn

there’s only four.

We must believe there are no more,

The information

Comes from Corps.

So onward to Bologna—

drive onward to the Po!

Another, more famous line, “We are the D-Day dodgers—in sunny Italy” was sung with particular emphasis in the cold October rain.

Despite their doubts about another winter campaign, the Hasty Ps went about their task with consummate skill. The British 56th Div. had won a shallow bridgehead across the Fiumicino and occupied the village of Savignano before handing over to 1st Canadian Brigade. The Hasty Ps, with a squadron of Strathconas, carved a deep salient into the German lines well beyond the New Zealand Div. that had been held up by stronger resistance. With artillery and air support the Hastings and Strathconas, who had never worked together before, in “a spontaneous demonstration of genuine, wholehearted co-operation between infantry and tanks” attacked out of the salient into the flank of the 90th Panzer Grenadier Div. which was blocking the New Zealand advance. The 48th Highlanders joined in and the Germans began to withdraw towards the town of Cesena and the Savio River.

The Loyal Edmonton Regt., now commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel J.R. “Big Jim” Stone, was the first to reach the enemy rearguards. Stone had served in every appointment in the regiment from private to regimental sergeant major and was admired in the battalion for his courage and concern for every soldier under his command. Stone carried out his own reconnaissance and decided on a silent night attack. The squadron commander from one of the regiment’s familiar partners, the 12th Royal Tanks, found a crossing and together they forced an enemy withdrawal to the Savio.

The Royal 22nd Regt. led 3rd Brigade’s advance to Cesena. Lt.-Col. J.C. Allard commanded a battle group that included two troops of tanks, a platoon of heavy mortars, plus a troop of self-propelled anti-tank guns. The Carleton and York Regt. passed through and reached the town centre late on Oct. 19. It was, as usual, raining and the Savio was threatening “to lose its banks.” The best news was that 10th Indian Div. was across the river a few miles to the west and 4th British Div., was to cross the next morning.

Urban expansion had blurred the outlines of Cesena’s old town and with a 21st Century population of 100,000 spread out beyond the river, the main visible landmark left is the town fortress on a craggy extension of an Apennine ridge. Below the castle, winding streets—lined with houses—show no signs of the battle that raged here in 1944. North of the town the Savio widens near the village of Martorano where the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry was the first Canadian battalion to try and cross.

The Canadian official history of the Italian Campaign describes the Savio as “a strong natural military barrier, at all times a tank obstacle, and when in flood, virtually impassable to infantry,” so it is not unreasonable to wonder what prompted the order to send the PPCLI across a rapidly rising river before the results of 4th Division’s crossing were known. The Canadians were supposed to be supporting V Corps, not the other way around, and the Savio was a much less formidable upriver in 4th Division’s sector. To make matters worse, the PPCLI was to cross on its own—there was no prospect of tanks joining since the river lay in a muddy trough 15 feet below the dikes lining the bank.

When Lt.-Col. R.P. Clark called his orders group on the afternoon of Oct. 20, British battalions were across the river 500 yards southwest of Cesena. Despite this there was no change in the Canadian brigade’s orders and two PPCLI companies began to cross while the early evening light still held. Sydney Frost’s memoir, Once a Patricia, describes the scene: “The whole front erupts in one tremendous roar. Shells scream over our heads. Mortars fill the air with deadly missiles. Tons of steel land on the far side of the river and explode in sheets of flame and clouds of dust and smoke. Able and Dog companies rise from their positions as one man…and surge forward to the riverbank. The barrage lifts 100 yards. The Germans stream out of their dugouts and run to their weapon pits. Smoke… gives our troops little cover… our men start to fall. German tanks are seen closing up the river.”

The Patricia’s Dog Company went to ground before reaching the river, a small group—17 men of Able Co.—got to the far side and clung to positions along the bank.

Brigadier Pat Bogert decided to commit both the Seaforths and Edmontons to the battle, using the darkness to get the lead companies across. The Savio was still rising as the advance began and the surface was black with an oily mixture that saturated the uniforms of the men wading across the river. The Loyal Eddies reached a cluster of houses beyond the Savio and held them against enemy infantry and armour. The Seaforths gained an equally small bridgehead, employing their tank-hunting platoon equipped with PIATs and Tommy guns to counter the threat by “a German force consisting of four Panther tanks, two self-propelled guns and 30 infantrymen.”

Sergeant K.P. Thompson positioned the tank-killers to trap and destroy the German armour. Placing a string of anti-tank mines across the road, he put the PIAT teams in ambush position. The lead enemy vehicle, a self-propelled gun, hit a mine, breaking its track. It came to a halt and was quickly destroyed. Private Ernest “Smokey” Smith dealt with the next arrival, a Panther, by stopping it with a single shot at a range of 30 yards. Smith then held his position against German panzer grenadiers and rescued his team partner who had been wounded in the encounter. Smith earned the Victoria Cross for his “dogged determination, outstanding devotion to duty, and superb gallantry.” Major Stewart Lynch, the company commander who recommended the award, noted that “it was a section commander’s battle…and each did his job more than admirably. Some were luckier than others, some results more spectacular, but I can assure you when it came to the question of awards it was a very difficult decision to favour one over the other.”

The next morning the bridgehead was far from secure. The Savio, running as deep as 16 feet, was in full flood and the engineers could not construct a bridge on the water-softened banks. As the rain eased, slings and rafts were used to transport basic supplies, including rum and PIAT bombs. The saturated ground was also causing problems for the enemy who complained that their counterattacks were foiled because “our tanks bogged down.”

On the night of Oct. 22, D Co. of the Patricia’s was ordered to cross the river at a point where engineers believed a bridge could be built. Before the advance could begin, the rain returned and when the lead Patricia’s bumped into a German patrol, all surprise was lost and a chaotic battle developed. The West Nova Scotia Regt., temporarily under 2nd Brigade’s command, did manage to get two companies across and one company was able to establish itself in a farmhouse 300 yards beyond the river. Major J.K. Rhode, who was awarded the Distinguished Service Order for his actions, held off counterattacks with the assistance of his PIAT team and the artillery. The next morning enemy fire destroyed the farmhouse and Rhodes had to direct the battle from a shell hole. A troop of self-propelled guns from 1st Anti-Tank Regt., Royal Canadian Artillery, knocked out a particularly aggressive German assault gun but the engineers reported that the rain had softened the river banks, ending all attempts to bridge the river. Rhodes and his men withdrew under a smokescreen, leaving the Edmontons and Seaforths clinging to their precarious positions.

The 5th Cdn. Armoured Div. had relieved the New Zealanders at the Savio and Burns outlined a plan for a new attack. Burns did not know, or did not appreciate, the significance of 4th British Division’s success west of Cesena where tanks were across the river. When he explained his intentions to the army commander, Burns was told to cancel further offensive operations. That night Canadian patrols reported a German withdrawal allowing the engineers to construct a bridge and bring tanks across the river. The new Eighth Army commander, Lieut-Gen. Sir Richard McCreery sent a congratulatory letter to Brig. Pat Bogert praising 2nd Brigade’s efforts as “a great example of how determined, well trained infantry can destroy enemy tanks with their weapons.” The men of 2nd Brigade who together with the West Novas had suffered 191 casualties, 33 of them fatal, were less sure that they had won an important victory as the Germans simply withdrew to the next river line.

Ravenna

The Battle for Italy’s Savio River, Oct. 20-23, 1944, marked the turning point in the difficult relationship between Lieutenant-General E.L.M. Burns and his senior officers. Despite the success the Canadian Corps enjoyed under Burns’ leadership, his two divisional commanders had begun to echo British complaints about his style of command.

Burns, who was ironically nicknamed Smiley, lacked the kind of easy-going leadership skills that were so highly valued in the Eighth Army. His relations with the brash, profane divisional commander Chris Vokes had always been difficult, but in the misery of the October battles another divisional commander, Bert Hoffmeister, “lost all confidence” in his corps commander, complaining that Burns “interfered with forward commanders.” Hoffmeister stated that “in spite of his best intentions” he was “inclined to be insubordinate” and he asked that either he or Burns be relieved of command.

Staff officers at Corps Headquarters reported that the tension between Burns and his subordinates made the atmosphere at conferences “unpleasant and embarrassing.” The divisional commanders “ignore Burns’ directions” and the corps commander “lacked the personality or ability to obtain co-operation.” Lieutenant-General Dick McCreery, the new commander of the Eighth Army, and General Harold Alexander were momentarily tempted to try their preferred solution, breaking up the corps and placing the Canadian divisions under British command. However, the Canadians would never have accepted this move and so McCreery reluctantly agreed that “Vokes would be acceptable” as a replacement.

In his memoirs titled General Mud, Burns, who was unaware of the role Hoffmeister and Vokes had played in his removal, recalled that he “did not believe it would be sound policy to continue an all-out offensive, and to incur further heavy casualties under the conditions in Italy’s Romagna region, where prospects for decisive victory during the winter months of rain, snow and mud appeared negligible.” Burns made no secret of his view and he thought this difference of opinion was behind McCreery’s decision to fire him.

The final decision to remove a Canadian corps commander could only be made by the senior Canadian officer General Harry Crerar who had defended Burns when the British had sought to replace him after the Liri Valley battles. Now, with Canadian officers demanding a change, Crerar had little choice. He was, however, determined to appoint a new corps commander from outside the Eighth Army who would understand that Canadian and British interest were not always identical. Crerar’s choice, Charles Foulkes, had been less than impressive as a divisional commander, but he did possess good organizational skills.

Sending Foulkes to Italy presented a problem because in the small Canadian professional army everyone knew that Vokes could never work under Foulkes. The two men could not stand each other. Vokes was, therefore, brought to Holland to take over 4th Armoured Division, replacing Harry Foster who was sent to Italy to command 1st Infantry Div. In the meantime, acting generals were appointed. Fortunately, the Canadians spent most of November in reserve, so there was time for officers to get used to new command styles while the combat troops, deeply weary after two months of action, got some rest.

Finding accommodations for 80,000 men in the shattered towns of eastern Italy was no easy task. The 11th Bde. ended up in the beautiful and undamaged city of Urbino while the rest of 5th Div. was scattered along the coast. The battalions of 1st Div. needed replacements as well as time to recover from the agonies of the Savio battle, but they were also told to reorganize for the next offensive.

A new anti-tank company was authorized to provide better protection when the supporting armour was held up by water barriers. It was equipped with the “Little John”, a high-velocity version of the old two-pounder anti-tank gun. The first Wasp and Crocodile flame-throwers had arrived in Italy and the lessons learned from using these highly effective weapons in Northwest Europe were passed on in demonstrations and training films.

All of these efforts to increase combat effectiveness were necessary because the battle for the Savio River crossing had deeply affected the morale of Eighth Army’s infantry battalions. Self-inflicted wounds, absence without leave and desertion became major problems and the Canadians were not immune. The Historical Officer attached to 1st Cdn. Div. noted that the October attacks had been marred by inadequate preparation time, useless or impossible tasks and shortages of manpower at the sharp end. He quoted the words of a Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry company commander who reported that poor morale was due to the belief that the war would be over soon, the recollection of last winter’s misery, the belief that the Gothic Line battles were supposed to be the last show for Canadian infantrymen in Italy and general war weariness, “especially in Italy.” The officer added that these morale problems were not unique to the PPCLI; “at the present time all brigades are busily occupied with Courts Martial, chiefly desertion and Absence Without Leave charges.”

Given the problems of weather, terrain, manpower shortages and morale issues, the decision to continue an all-out offensive in Italy needs to be understood. The orders issued to Alexander in early November 1944 required 5th and 8th Armies to “maintain maximum pressure… in early December” when Eisenhower was hoping to launch a major offensive in Northwest Europe—an offensive that was delayed, then postponed indefinitely when the Germans attacked through the Ardennes in the Battle of the Bulge.

While the phrase “maximum pressure” was subject to interpretation, the intent was clear; tie down German troops in a holding action to prevent them from transferring divisions out of Italy. Alexander, backed by Churchill, would not accept this limited role and so he continued to plan for “a two-handed punch—the right hand punch by 8th Army across the Adriatic and the left hand strike by 5th Army on the Italian mainland…both Armies converging on the Trieste.…” Once Trieste was secure, Alexander proposed an advance to Vienna through the Brenner Pass.

This ambitious and deeply flawed plan was scheduled for early 1945, requiring an all-out offensive to secure the cities of Bologna and Ravenna in the last weeks of 1944. The Joint Chiefs did not accept Alexander’s plan for Trieste and Vienna but they did authorize a renewed offensive in Italy “to contain German Field Marshal Albert Kesselring’s armies.” With Bologna and Ravenna as objectives.

While the bulk of the Canadian Corps was enjoying a month out of the line, the Royal Canadian Dragoons, 2nd Field Regiment, Royal Cdn. Artillery, 5th Medium Regt., RCA, and the 12th Field Company, Royal Canadian Engineers, joined British gunners and the 27th Lancers tank regiment in a battle group known as Porterforce. Its task, to protect the right flank of V British Corps and capture Ravenna, seemed too ambitious for 2,000 men, no matter how much firepower it had. As the RCD history relates, “the enemy had opened the dikes of the Savio and flooded the area so that the road (Route 16) was under water in places and in others ran like a causeway across the drowned countryside. Troops and vehicles moved on that highway like the targets in a penny shooting gallery.… In its worst dreams, the Regiment had never seen itself advancing in such a position.”

A slow, artillery-supported advance was nevertheless possible and on Nov. 1, the RCDs were delighted to learn that Popski’s Private Army was to take over the coastal flank. The arrival of several hundred Italian partisans—part of the Garibaldi Brigade—further strengthened Porterforce.

The leader of the partisans Arrigo Boldrini, who used the nom de guerre Major Bulow, made his way to Canadian Corps headquarters on 20 November. He sought to co-ordinate the actions of his 28th Garabaldi Brigade with the Canadians in the liberation of Ravenna. Captain D.W. Healey, an Italian-speaking officer of the corps intelligence staff, joined Bulow to maintain communication with Porterforce. Setting out in a row boat Healey and Bulow reached a beach well behind enemy lines

No sooner had we beached our craft than the shrill cry of a night hawk rang out. One of our oarsman replied and we were soon surrounded by a band of armed cut-throats… who lifted out craft onto an oxcart. A rear party worked to cover our tracks… then women and children from the neighborhood… finished the job.

Healey sent off a request for the supplies that would make the brigade a more effective force, especially ammunition and gun oil to lubricate the weapons. Healey participated in a major raid designed to determine the strength of German mobile reserves. His report offered this description:

After dinner three companies, total strength 150 men set off for Porto Corsini. We went through a maze of canals in small boats and finally landed at a point where we could hear Germans singing in their billet 500 yards away. The partisan crowed forward to within 150 yards…

After a volley cut down the sentries a firefight developed Bulow ordered a withdrawal leaving an ambush party. Healey reported,

Enemy force… estimated at 50 reacted to our attack. We silenced two machine guns and inflicted casualties. Details not yet available. Troops still leaving Ravenna. Some went north-west to reinforce Porto Corsino after partisan attack.

Using the aged and infirm, women and small boys as runners Healey got information through to Corps headquarters, including locations of enemy artillery. Bulow’s men entered Ravenna meeting Porterforce and Canadian armour.

The liberation of Ravenna was accomplished on the eve of Eighth Army’s next offensive, an operation given the wildly inappropriate name, “Chuckle”. Both Canadian divisions were begin an advance on Dec. 2, assuming responsibility for a 16-kilometre-wide front on Eighth Army’s Adriatic flank. The Canadians faced a flat, saturated landscape crossed by ditches, canals and three rivers, the Lamone, Senio and Santerno—all with diked banks. The enemy had improved these man-made obstacles by scooping out tunnels “revetted with stout timbers with openings the size of ship portholes. From these holes protruded the ugly muzzles of the enemy’s guns.”

These mutually supporting positions along the meanders of the rivers allowed the defenders “to sweep a wide front with converging and enfilade fire.”

The bridges had all been destroyed, presenting the engineers with a formidable challenge. One possible solution was the Brown Bridge developed by Captain B.S Brown of 4 Field Company, Royal Canadian Engineers. The bridge could be carried forward on two tanks and used to cross an 80-foot gap. A second invention, the Olafson Bridge, developed by Capt. E.A. Olafson, Royal Canadian Electrical, Mechanical Engineers, could be quickly constructed out of portable sections of half-inch pipe to provide an infantry footbridge. Olafson bridges were constructed for each infantry battalion before Operation Chuckle began.

Brigadier J.D. “Des” Smith, the Acting Commander of 1st Cdn. Div. reminded battalion commanders of the enemy’s pattern of holding each water barrier long enough to force a set-piece attack then quickly withdrawing to the next barrier. Smith stressed the need to get patrols up to the next obstacle “as soon as a bridgehead has been formed.” The enemy was thin on the ground and everyone “right down to the company level” must move forward and forget about flanks. “Avoid house fighting,” he argued. The best course was to use artillery, “bring down fire before we reach them.”

This was no doubt sound advice, but the real problems confronting the infantry were the dike defenses. Major-General C.E. Weir, who left the New Zealand Div. to command the 46th British Div. in November, had gone so far as to forbid his infantry to cross rivers “unless tanks and anti-tank guns could bring their immediate support.” No such restriction was proposed by Canadian commanders.

The 3rd Cdn. Inf. Bde. led off the attack from a bridgehead that 10th Indian Div. had secured across the Montone. Their task was to clear the town of Russi, then seize a crossing of the Lamone, three kilometres to the north. Today, Russi is a pleasant town of 10,000, popular with visitors to the archeological museum and the mosaics of the nearby Villa Romano. Veterans of the 1944 battle would not recognize the place that was hammered by air strikes and artillery in those dismal December days.

The West Nova Scotia Regt. and the Royal 22nd Regt. reached Russi after overcoming some tough enemy delaying positions. Brig. Paul Bernatchez ordered a night advance to the Lamone, but it quickly became apparent that the railway embankment which crossed the entire front north of Russi was a main line of resistance. After two hastily prepared attacks failed, Bernatchez added his reserve, the Carleton and York Regt., to a three-battalion night attack, supported by extensive artillery concentrations. The enemy withdrew to the river and 3rd Bde. quickly overcame the rearguards, reaching the Lamone to find the bridges blown and the far bank strongly defended.

The German withdrawal from the railway embankment had been hastened by the actions of an aggressive battle group leading 5th Armoured Division’s advance to Ravenna. The Princess Louise Dragoon Guards and the Lanark and Renfrew Scottish Regt. led while the Westminster Regt. captured a vital crossing of the Montone River, opening up a supply route. The operations log of 12th Bde. proudly recorded the results of this speedy and successful advance that carried the brigade “through the enemy’s delaying line (the railway) east of the River Lamone.”

Ravenna was now outflanked and on the night of Dec. 3-4, local partisans reported that Ravenna was undefended. The PLDGs, partisans and Lt.-Col. Porter’s regiment, the 27th Lancers, all reached the city centre at about the same time.

During the first three days of Operation Chuckle, the two Canadian divisions had suffered 211 casualties evenly divided between 3rd and 12th Bde. A similar number of men had been evacuated as non-battle casualties. In the cold calculus of the war, this was an “acceptable” wastage rate for the capture of Ravenna, one of the main objectives of the offensive.

The Lamone and Senio Rivers

The original plan for I Canadian Corps’ Operation Chuckle, December 1944, called for the capture of Ravenna and an advance beyond the Senio and Santerno rivers to the town of Massa Lombarda. If the Canadians succeeded, their thrust would outflank German positions at Imola and threaten the enemy’s hold on Bologna further to the west. While Ravenna was liberated on Dec. 4, the 1st Canadian Division suffered a serious reversal when a hastily prepared attack across the Lamone River failed, forcing a withdrawal.

Two battalions of 1st Brigade, the Royal Canadian Regiment and the Hastings and Prince Edward Regt., suffered close to 200 casualties in this ill-advised, chaotic action. For the Hasty Ps, Dec. 5 was a particularly black day as their own medium artillery struck them down on the banks of the river.

Fortunately, 5th Armoured Div. reached the Lamone in good order where it paused to prepare for a proper co-ordinated assault crossing. The Eighth Army commander, McCreery, had promised that his troops would “not have to fight both the weather and the enemy.” So, the attack was postponed when heavy rain began to fall. The enemy took full advantage of the respite and the weather, which limited air operations, to reorganize their forces. The fighting strength of German battalions averaged less than 250 men, raising the possibility of a more favourable force ratio for the Eighth Army if something could be done to get Allied armour across the water obstacles.

During the weeklong wait a series of command changes took place. Both Brigadier Allan Calder and Lieutenant-Colonel J.W. Ritchie, commanding officer of the RCRs, were replaced due to their “failure” in the abortive attack across the Lamone. Ironically, Brig. J.D. Smith, who as acting divisional commander had ordered the improvised assault, was given command of Calder’s brigade when Major-General Harry Foster arrived from Holland to take up his appointment as divisional commander.

Foster presided over his first Orders Group on Dec. 10, confirming the division’s part in a corps attack scheduled for that night. Third Bde. Brig. J.P.E. Bernatchez was to take the first bound in an effort to create a half-mile-deep bridgehead across the Lamone. If all went well, 1st Bde. would follow and press forward to Bagnacavallo, a town astride the Canale Navaglio. Since the action was to take place on the same stretch of river that the 1st Bde. had failed to secure, no effort was spared in preparing for the new operation.

This time, both Canadian divisions would launch a simultaneous assault while a British brigade staged a feint attack. Two medium artillery regiments with increased ammunition allocations were available, and when dawn broke, the RAF would, weather permitting, engage the enemy employing a new method of air-to-ground support known as Timothy Targets. Using flights of 12 aircraft and direct contact with a Forward Air Control Post, pilots were briefed to strafe and bomb areas to a depth of 1,000 yards in front of a Bomb Safety Line identified by smoke. Marauder B26 medium bombers were tasked to destroy a long list of identified targets.

Bernatchez was given command of an additional battalion of the 48th Highlanders for the crossing, allowing the use of three battalions in the initial assault. The 12 Royal Tank Regt. provided direct fire during the crossing’s first phase. The regiment had been reorganized to include a Crocodile flame-throwing squadron, but this invaluable force-multiplier was not in range during the Lamone crossing. “Assault boats and Olafson footbridges were allotted to each infantry battalion and sufficient Mae Wests (inflatable life jackets) to protect the infantry during the crossing were provided.”

The German Army’s 356 Infantry Div., one of three divisions available to LXXVI Corps on the far bank of the river, was focused on the obvious crossing points near the remains of a railway bridge. The West Nova Scotia Regt. drew this sector with the Carleton and York Regt. and the 48th Highlanders on the flanks. During the rain-imposed delay, the banks of the river had deteriorated and by Dec. 9 the water was 60 feet wide and rushing between steep dikes.

Invicta, the history of the Carleton and York Regt., offers a description of the preparations.

Getting the heavy boats to the water was a hard slog: they had to be dragged 600 yards through mud up to the ankles by men already burdened with weapons, ammunition, and equipment. The boats went down in single file to within 100 yards of the dike and then branched into three sections of two boats…. The boats were then dragged with great expenditure of effort to the top of the 30 feet high dike, and slid down the other side…with moments to spare before H. Hour.

The Carletons and the 48th Highlanders got across before the enemy had recovered from the accurate artillery program, but in the centre, the West Nova Scotia Regt. ran into stiff opposition. The West Novas had elected to cross the river using the Olafson footbridge, but the current and problems with flotation demolished the bridge. The dilemma was solved by passing the assault companies through the other bridgeheads and attacking along the dike to the bridge embankment. The Royal 22nd Regt. joined its sister battalions before dawn and at first light began moving forward on a two-company front supported by the medium machine-guns of the Saskatoon Light Infantry as well as effective close air support and accurate mortar fire.

The brigade objective, the Fosso Vecchio, was less than 500 yards away but—as predicted—the Germans had withdrawn to prepared defences behind the creek. Attempts to rush the position proved too costly to continue.

Hoffmeister had selected his veteran 11th Inf. Bde., with the British Columbia Dragoons under command, to cross the Lamone near the village of Villanova. The initial two-battalion attack was to be silent with the artillery on standby. If surprise was lost, the code word “Bedlam” would bring instant support on pre-arranged targets. The Perth Regt. was able to obtain surprise and was swiftly across, but the Cape Breton Highlanders signalled Bedlam shortly after their boats hit the river. Both battalions seized their initial objectives allowing Brig. Ian Johnston to send the Westminster and Irish regiments across to expand the bridgehead.

The expected enemy counterattacks were defeated with the Westminster’s tank-hunting platoon claiming the destruction of four tanks. By the evening of Dec. 11, elements of two Canadian brigades were ready to tackle the Fosso Vecchio defences, and seize the crossing over the Canale Naviglio. Hoffmeister committed the relatively fresh 12th Bde. in the 5th Division’s sector. Major-General Foster decided that despite, or because of, the morale problem that had shaken the resolve of the RCRs and Hasty Ps at the Lamone, they would take on the Naviglio, saving 2nd Bde. for what he hoped would be a rapid advance to the Senio and beyond.

The decision to continue an operation that was costing the Canadians a steady stream of casualties, killed, wounded, and missing, not to mention a growing number of battle exhaustion cases requires explanation. When the army commanders met in Rome in November of that year they had agreed that their purpose was “to afford the greatest possible support to the Allied winter offensives on the Western and Eastern Fronts by bringing the enemy to battle, thereby compelling him to employ in Italy manpower and resources that might otherwise be available for use on other fronts.” They also agreed that “no attacks will be launched unless the ground and weather conditions are favourable.”

When McCreery returned to his headquarters he announced that Eighth Army’s task was to “render all assistance to the 5th Army in the capture of Bologna.…” McCreery had agreed that 8th Army would open the offensive, advancing to the Santerno River and drawing off German reserves before Fifth Army renewed its attempts to reach Bologna. By Dec. 11 two things were evident. First, the German high command had responded to Eighth Army’s offensive by transferring three divisions from the Bologna front. Second, reaching the Santerno without the assistance of Fifth Army was a pipedream. Nevertheless, McCreery ordered the Canadians, together with the Polish Corps, the New Zealand Div., and 10th Indian Div., to maintain pressure while Fifth Army prepared an all-out attack using heavy bombers the way they had been employed in Normandy to break through German defences.

Suddenly, sweeping changes in command intervened to create an atmosphere of hesitation at Fifth Army. General Harold Alexander was placed in overall command of the Mediterranean theatre with Gen. Mark Clark taking his place at Army Group. Gen. Lucian Truscott returned from France to take charge of Fifth Army. These events, combined with the uncertainty created when Hitler launched his Ardennes operation—the Battle of the Bulge—led Fifth Army to abandon plans for an offensive and prepare to meet a German attack. Why then did Eighth Army continue to press forward under such adverse conditions?

The answer is not easy or satisfactory. McCreery knew that the 98th German Inf. Div., supported by companies of Tiger and Panther tanks, had begun to deploy opposite the Canadians while other German units had reinforced the forces opposing V British Corps. McCrerry’s original orders to continue to the Senio River were based on the understanding that Clark would unleash Fifth Army. If this was now unlikely, continuing the advance would be a costly exercise. Those on the ground could see little advantage in pressing forward. There was no high ground to capture and the enemy was known to be still reinforcing the sector, adding the Kesselring Machine-Gun Battalion to the defences. There were other problems. The Germans had fortified the Naviglio and the towns of Bagnacavollo and Villanova, cutting down the trees that lined the canal to improve their fields of fire. Everything about the situation pointed to another difficult and costly operation especially for the Canadians who would do most of the fighting.

Would McCreery have ordered this advance if British divisions were involved? By December the 56th Division, reduced to two brigades and the 21st Tank Brigade in support of 1st Canadian Division were the only British brigades active in Eighth Army. The 46th Division had been withdrawn to intervene in the Greek civil war joining 4th British Division which had crossed to Greece on 12 December. V British Corps was now composed largely of Polish, New Zealand and Indian divisions.

Lieutenant-General Charles Foulkes, now fully in command of the Canadian Corps, did not question McCreery’s orders. A plan for a simultaneous advance by both his divisions was devised relying on massive amounts of artillery to suppress the enemy while the infantry crossed 700 yards of ground and the 20-foot embankment. The canal itself was dry, though bridging was prepared to assist the armour.

The Carleton and York Regt., followed by the Hasty Ps, made the crossing in 1st Division’s sector while the Lanark and Renfrew Regt. and the Princess Louise Dragoon Guards led 5th Division’s attack. After ten minutes of heavy concentrations from medium and field artillery, the field guns provided a rolling barrage. As had been so often demonstrated, good infantry, with enough support, could usually take a well-defined, limited objective. The challenge was to consolidate, dig in, and deal with enemy counterattacks with limited anti-tank assets and the inevitable communication breakdowns.

Both bridgeheads came under severe pressure. The Princess Louise Dragoon Guards were “cut into isolated segments by furious counterattacks. Much of a Hasty Ps’ company was surrounded and taken prisoner. The Lanarks were stopped cold. The Carletons held on, but were forced back to the canal. The weather, to no one’s surprise, cancelled air support while enemy artillery observers, occupying two high towers in Bagnacavollo directed accurate fire on the narrow bridgehead.

By midday, Dec. 14, anti-tank guns and Sherman tanks of the British Columbia Dragoons had entered the bridgehead relieving some of the pressure. Late in the day, the Westminster Regt. crossed in the 1st Div. sector and advanced north along the canal, breaking the German ring around 5th Division’s position.

The enemy was gradually forced to concede ground, but fighting for the narrow slice of ground, just two miles wide at its apex, continued for another week. Bagnacavollo, or what was left of it, fell on Dec. 21. The day before, Clark, who clearly knew little about the condition of Eighth Army, announced that “the time is rapidly approaching when I shall give the signal for a combined all-out attack by 5th and 8th armies.” Instead, the Germans launched an attack on Fifth Army’s weak right flank and all major offensive operations ended. Alexander, now a Field Marshal, agreed to “go on the defensive for the present and concentrate on making a real success of our spring offensive.”

As Eighth Army prepared to defend the Senio River line two salients still occupied by the enemy had to be cleared. While preparations for these actions, scheduled for early January, were underway the Canadian Corps commander Charles Foulkes gathered his officers, lieut-colonels and above, in Ravenna. Foulkes declared that a high proportion of the 2000 casualties the Canadians had suffered in December, 22 officers and 420 other ranks, were listed as missing. Such casualties as well as battle exhaustion were, he said, due to “faulty junior leadership and/or poor morale.” It was, he said, “imperative to improve morale and leadership.” Nothing was said about dubious command decisions by senior officers.

A “Report on Operations 10-21 December” issued by 5th Armoured Division offered a more realistic explanation of the casualty toll:

The whole of the action from the Lamone to the Senio had been characterized by heavy mortar and shell fire. The country was very open, little cover other than canals and ditches was available. This made accurate fire on the part of the enemy comparatively simple… Coupled with this was the fact that forward troops had to remain in slit trenches in ground that would have been wet even without the rain that accompanied us throughout the operation.

The first of the “minor tasks” carried out by Eighth Army in January, the clearing of the Gararola salient required 2nd Canadian Brigade to assist 56th British Division by capturing the village of Gararola. This was speedily accomplished and British troops occupied the south bank of the Senio river.

The operation to clear the enemy from the south side of the Valli di Comacchio met much stronger resistance but 11th Brigade, employing “artificial moonlight”, search lights aimed at dense cloud cover, broke through the enemy opposition at Conventello setting the state for 5th Armoured Brigade. Taking advantage of frozen ground around the Breitish Columbia Dragoons “pushed forward engaging all houses, barns and haystacks.” The New Brunswick Hussars paralleled the BC Dragoons until stopped by “a deep roadside ditch defended by self propelled guns and Panther tanks.” The Cape Breton Highlanders joined the Hussars and after a sixty minute artillery program ended, dealt with a German counterattack. The British Columbia Dragoons, further east, were repeatedly counterattacked by enemy armour but checked each attack. Working with Perth Regiment infantry they crossed the Bonifica Canal and completed the division’s task.

The 5th Canadian Armoured Division was withdrawn on 14 January 1945, replaced by the Cremona combat group of the regular Italian Army. 1st Division remained in position on the Senio River well into February despite the decision taken at the Malta Conference (30 Jan to 3 February) endorsing Canadian demands to reunite I Canadian Corps with First Canadian Army in the Netherlands. On the night of 24 February, the Seaforth Highlanders and Loyal Edmonton Regiment fought the division’s last battle on Italian soil suffering 9 fatal casualties and 26 wounded. Operation Goldflake, the transfer of the Corps to Northwest Europe began in mid-February and was complete by late March. Few regretted leaving Italy and the prospect of Alexander’s spring offensive.