Clearing The Gully

Historians have tended to treat the battle for the Moro River–fought in Italy between Dec. 6 and 10, 1943–as a prelude to the better known struggle in the streets of Ortona. However, at the time, the battle for the Moro was seen as an important victory opening the way to Eighth Army’s real objective: Pescara.

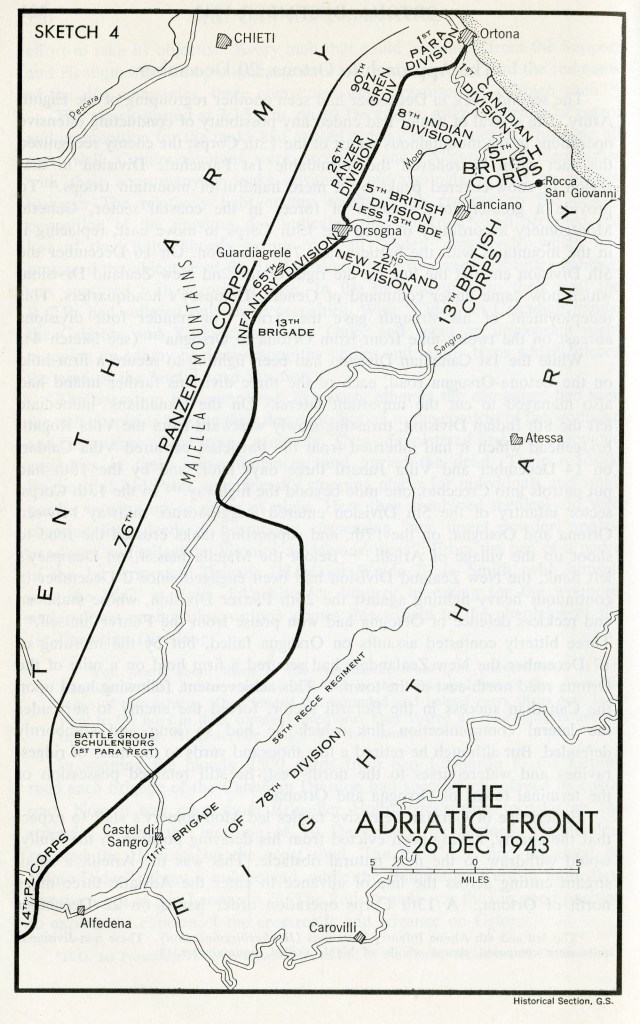

When the 90th Panzer Grenadier Division reported it could no longer contain the Canadians in the bridgehead, the German commanders ordered a rigorous defence of the approaches to Tollo, a village west of Ortona. If the Canadians reached Tollo they would bypass Ortona and continue north to Pescara without becoming involved in a house-to-house battle.

The Germans had suffered heavy losses in a series of counter-attacks against the Canadian bridgehead, including a last desperate attempt on the evening of Dec. 9. Allied artillery had frequently failed to provide accurate fire support during offensive operations due to inaccurate maps and dubious meteorological reports on wind speed and direction. But when the Germans attacked, Forward Observation Officers (FOOs) corrected the fire, thus bringing the guns of 1st Canadian, 8th Indian and a medium artillery regiment to bear on the exposed attackers.

December 9 had been a historic day. The diarist at the Canadian Division’s headquarters wrote that it “…will be remembered by the 1st Canadians for a long, long time. We had our first real battle on a divisional level with the Germans–the battle of the Moro River. The Germans counter-attacked very heavily and were thrown back.” Montgomery sent his “hearty congratulations” but renewed his orders, Lieutenant-General Charles Allfrey’s V Corps was to press the advance to Tollo with 1st Canadian and 8th Indian divisions maintaining pressure until Eighth Army was reorganized and ready to carry out Operation Semblance, a four-division advance designed to reach the Pescara-Rome highway.

Thus began the struggle for what Canadian soldiers called The Gully, a feature formed by the Fosso Saraceni, a small creek that had worn a U-shaped valley into the landscape. The Gully was barely noticeable on the large scale maps of the area and had failed to draw the attention of intelligence officers or air photo interpreters, but the 200-metre-deep ravine provided the enemy with ample opportunity to fight effectively from terrain that gave the defender every advantage.

The Loyal Edmonton Regiment, with a squadron of Calgary Tanks and a platoon of medium machine-guns from the Saskatoon Light Infantry, began the push north on the morning of Dec. 10. The battle group included two FOOs from 3rd Field Regt. and one from the corps medium regiment. Their goal was Cider Crossroads, the point where the San Leonardo-Tollo road met the Ortona-Orsogna highway. If all went well the 2nd Brigade would turn east towards Ortona to outflank the defenders south of the city while 3rd Canadian Infantry Bde. would join an Indian brigade in the advance north to Tollo. The occupation of the village, with its network of minor roads to the north and east, would force the enemy to abandon Ortona, leaving it intact for the Allies to utilize as a base.

The road the Loyal Eddies followed skirts a creek defile before turning east. Today the A13 Autostrada, elevated above The Gully, dominates the battlefield, but in 1943 the narrow road ran through an apparently empty countryside. Accounts of the day’s events vary widely, but everyone agrees that all attempts to advance to The Gully–never mind the crossroads–were met with concentrated machine-gun and mortar fire which neither the artillery nor the mortars could suppress. A vague message sent to brigade at 1:30 p.m. reported “3 coys (companies) on objective are consolidating.” This signal must have been intended to refer to the first-stage objective, not Cider Crossroads. But Brigadier Bert Hoffmeister misunderstood and ordered the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry to join the advance, securing the high ground the Patricias would call Vino Ridge. They came under heavy, observed fire and were forced to stop and dig in just east of San Leonardo.

The Seaforth Highlanders of Canada had kept pace with the Loyal Eddies, protecting their left flank. But they, too, suffered from accurate enemy fire. Lieutenant-Colonel J.D. Forin was among the wounded and he provided this graphic description of his evacuation to the regimental aid post (RAP). “The Advance RAP is in a house 50 yards behind the gully. It is full of wounded and shocked men…. An RAP Jeep arrives…King (Forin’s runner who was also wounded) and I are loaded on it. King is unconscious, but breathing. The Jeep creeps cautiously down the shell-pocked road to San Leonardo. I think that if I were driving I would go all out. Shells blossom on the road on both sides but the driver has critically wounded aboard and to hit a shell hole at high speed might kill them…. The RAP is a dark room in a battered house. Lights from car batteries hung over blood-stained stretchers… fresh casualties keep arriving. The MO (medical officer) is desperately tired, but he never stops working or loses patience with the shock cases.”

The enemy was not content with stopping the Canadians. The 90th Div. was told to regain the ground above the Moro. The first wave of German attacks began on the afternoon of Dec. 10. The next day three separate attempts to overwhelm the Canadians produced heavy casualties on both sides. General Traugott Herr, the German corps commander, complained that these attacks “had been committed too late in the day and had been half-hearted.” He removed the divisional and regimental commanders, placing the division under the command of Col. Ernst-Günther Baade of 3rd Para Regt. Baade was an experienced commander who was prepared to do whatever it took to slow the Canadian advance at least until the balance of 1st Para Div. arrived.

The 8th Indian Div. had enjoyed slightly greater success on its axis, reaching Villa Caldari just south of the Ortona-Orsogna road. The Gully did not extend this far inland and there were good prospects for a further advance, but the Indian battalions were understrength and near exhaustion so they were allowed to pause and regroup. When the advance was renewed, the enemy was well dug in and able to hold positions in front of the lateral road for more than three days.

Montgomery proposed to begin Operation Semblance on Dec. 15, but Allfrey and Major-General Chris Vokes–the Canadian divisional commander–wanted the Canadians to secure Cider Crossroads and the highway before joining in the promised corps advance. Vokes decided to commit his reserve, the 3rd Canadian Infantry Bde., to accomplish this. The West Nova Scotia Regt. made the first attempt at dusk on Dec. 11, but could make no progress. The next morning, they were ordered to try again, despite a driving rain. When this attack failed, Vokes employed all available three-inch and 4.2-inch mortars with their high-trajectory fire on the reverse slope, while the artillery suppressed other enemy positions. The Carleton and York Regt. led the new advance supported by flank attacks. After some early success, “murderous machine-gun and mortar fire” from within and beyond The Gully overwhelmed the battalion, which suffered 52 casualties as well as the loss of 28 men who were taken prisoner when a platoon was cut off.

As another frontal attack collapsed under the German fire, a battle group formed by a company of the West Novas, a tank squadron from the Ontario Regt., combat engineers and a troop of self-propelled guns, found and destroyed a German battle group deployed to defend the shallow western end of The Gully.

A platoon of West Novas, with a troop of tanks from the Ontario Regt., charged the enemy position, destroying two German tanks and capturing the others. A second troop of four Ontario Regt. tanks, working closely with a Seaforth Highlander company, swung further to the left, circling around the enemy defences before probing east towards Casa Berardi. This brilliant stroke, which might have ended German resistance at The Gully, could not be supported as Vokes had no reserves immediately available. With the tanks low on fuel and ammunition, the best the battle group could do was to defend their position near the Ortona-Orsogna road.

These probing attacks on the left flank of the Canadian sector were assisted by a renewed effort from 8th Indian Div., which committed an armoured-infantry battle group to a night attack towards Villa Grande. The Germans were forced to send local reserves to seal off this penetration, allowing the Canadians to exploit a temporary seam in the enemy defences.

The decision by Vokes to commit two 3rd Bde. battalions to a frontal attack on The Gully left the division with just one uncommitted infantry battalion, the Royal 22nd Regt. The Van Doos, as their comrades called them, were told to assemble with a squadron of Ontario Regt. tanks during the night of Dec. 13-14 and to use a divisional artillery program to advance northeast towards Cider Crossroads. The attack, which was to begin at first light on Dec. 14, would have to overcome a powerful enemy. While no great “fighting value” could any longer be ascribed to 90th Div., two battalions of 1st Para Div., whose strength “had been increased by the arrival of young reinforcements,” were now in position to block the Canadian advance.

Brigadier Bruce Matthews–the divisional artillery commander–was determined to improve the effectiveness of his guns. The base maps used to plan the unobserved or predicted fire in previous attacks had proven to be quite inaccurate so the artillery FOOs had worked hard to register the guns on a series of target areas that were given code names. And so rather than relying on a moving barrage, the hope was that FOOs with the forward troops could call for concentrations of fire on specific positions.

On the morning of Dec. 14, the Van Doos discovered just how valuable this flexibility was. Their first task was to recover control of the lateral road, not advance along it, so the 60-minute-long opening barrage was of little help. The infantry stalked a German tank hidden in a house before destroying it with a PIAT gun. Soon afterwards two companies, each supported by a troop of tanks, began an advance across “a wasteland of trees with split limbs, burnt-out vehicles, dead animals and cracked shells of houses.” The parachute battalions, assisted by tanks or self-propelled guns, were dug in among the ruins and craters ready to call upon artillery and mortars as well as their own fire to wreak havoc among the Canadians.

The right flank Van Doo company, turning to avoid such fire, ended up lost in The Gully before withdrawing to the start line. Major Paul Triquet’s “C” Company worked its way forward with the help of the Ontario Regt. Shermans. Matthews’s registered artillery concentrations and tank fire deserved much of the credit for the advance, but the raw courage of Triquet’s men was quite extraordinary.

With less than 20 men and five tanks left in his battle group, Triquet and Major H.A. Smith of the Ontario Regt. decided to seize and then defend the villa and farm buildings of Casa Berardi. Their determination to hold the Casa, expressed in Triquet’s phrase “mot d’ordre, ils ne passeront pas”, has become famous in the annals of Canadian history. The VC Triquet earned was well deserved, but the role of the Ontario Regt. tanks and the night march of D Co. of the Van Doos, which reached the Casa shortly before midnight, should also be remembered.

The successful defence of Casa Berardi did not mean the end of the battle for The Gully. The enemy continued to use this natural obstacle to block the advance of 1st and 2nd brigades. Vokes was an exceptionally stubborn man and he ordered the Carleton and York Regt. to make yet another frontal assault on Cider Crossroads. According to his own account–written well after the battle–“the attack was not pressed home and again failed in the face of determined opposition.”

Allfrey was later to claim that “he had a long talk with Vokes… and told him he was tiring out his division and producing nothing because of the lack of co-ordination.” Since Allfrey’s “diary” was written after the event, it is difficult to rely upon but if the “long talk” occurred on Dec. 14 it did not persuade Vokes to cancel the Carleton and York attack.

Finally, on the afternoon of Dec.15, Vokes decided on a 48-hour pause to organize a proper set-piece attack from the Casa Berardi position. The 48th Highlanders of Canada and the Royal Canadian Regt. were to move in behind the Van Doos and prepare to follow an extensive artillery program designed to shoot them onto objectives around Cider Crossroads.

The guns of nine field and three medium regiments would fire two artillery programs, Morning Glory–in support of the 48th Highlanders–and Orange Blossom for the Royal Canadian Regt. The 48th Highlanders were able to follow the “terrifying and effective” artillery fire in a deliberate advance carried out “at a rate of only 100 yards every five minutes.” They reached their objective north of Cider Crossroads just as the RCRs began their advance. Orange Blossom turned out as disastrous as Morning Glory was successful. For reasons that have not been explained, a large number of short rounds fell among Canadian troops, and Matthews cancelled or changed much of the fire plan. The RCRs ran into a number of untouched enemy positions and suffered heavy losses in what they described as a “death trap.”

Despite these losses the battalion was ready to resume the battle the next day. This time the artillery fire was both accurate and effective. The crossroads was secured and the battle for The Gully finally over.

Into Ortona

When Lieutenant-General Harry Crerar–a veteran of World War I–arrived in Italy to take command of I Canadian Corps, he was introduced to the battlefields of the Moro River and the Gully.

Strome Galloway, who was in temporary command of the Royal Canadian Regiment, recalled the visit in his memoirs:

Crerar stood in the frozen mud. Behind him was the shattered farmhouse which served me as my battalion headquarters and leaning on his walking stick he shifted his gaze from left to right and back again. ‘Why it is just like Passchendaele,’ he murmured. Since none of us had been at Passchendaele, and some of us were not even born then we could not challenge his assessment. So we nodded in agreement and heard even more about the mud of Flanders, the rainfall in the Ypres Salient, the misery of trench warfare as the general’s mind went back more than 25 years….

Crerar’s attempt to compare World War II in Italy to the battles of 1917 made him seem old-fashioned and out of touch to the young veterans who believed their war was unique, but Crerar was surely right. After two weeks of intense combat–with very heavy casualties–the Canadians had advanced some 2,500 yards, captured acres of muddy ground and a stretch of road that was still visible to the enemy. Their comrades in the 8th Indian, 2nd New Zealand and 5th British divisions had similar experiences while grinding out small advances of little operational significance. Orsogna–like Ortona–was still in enemy hands and there was no realistic prospect of reaching Pescara and the lateral road to Rome.

Despite the collapse of Operation Semblance–Montgomery’s last effort to reach the Pescara-Rome highway–two factors fuelled the requirement to continue offensive action. Mark Clark’s Fifth Army was preparing to launch what would become known as the first battle for Rome, including an attempt to secure Monte Cassino. Eighth Army was therefore ordered to “maintain pressure” in an effort to tie down German forces in the Adriatic sector. The second factor, which was specific to the Canadians, was the opportunity to secure Ortona as a port and rest area before the Italian winter arrived in earnest.

And so on Dec. 19, 1943, orders were issued to resume the offensive, and for the first time Ortona itself was the objective. The divisional and corps intelligence reports tried to offer encouragement, suggesting that “having lost control of the (Cider) Crossroads, the enemy is likely to fall back…abandoning Ortona.” However, no combat soldier still believed such forecasts. While front-line German commanders advised a withdrawal to the north before more battalions were destroyed, General Joachim Lemelsen, the German Tenth Army’s commander, disagreed. He believed the time had come “for the thorough annihilation of the British 8th Army.” No ground was to be given up until arrangements for a full-scale attack had been completed. No German combat sodleir believed him and Hitler, who was now micro-managing his forces in Italy, was far more concerned about the Allied threat to Rome and decided against a buildup on the Adriatic. He did, however, reject any suggestion of a withdrawal from the strong defensive positions on the Orsogna-Ortona front.

Canadian historians have usually focused their account of the battles of late December on the street fighting within Ortona. Descriptions of the tactics used by 2nd Brigade in clearing the town are frequently coupled with comments that Ortona should have been bypassed–something critics maintain would have forced the enemy to withdraw from town. Since bypassing the town was precisely the task assigned to 1st and 3rd Canadian infantry brigades as well as a brigade of the 8th Indian Div., such views confuse rather than clarify the Ortona story. The enemy certainly knew the Allies were attacking on a broad front and initially just one battalion was committed to defending Ortona, while four battalions were resisting the Canadian and Indian advance west of the town.

Vokes regrouped his forces before launching the new attack. The Seaforths took over the coastal road with orders to advance on Ortona in support of the main thrust to be made by the Loyal Edmonton Regt. The Hasty Ps rejoined 1st Bde. to begin the advance to Point 59, a prominent hill overlooking the coast north of Ortona.

The Loyal Eddies, with a squadron of tanks from the Three Rivers Regt., began the advance at noon on Dec. 20. Fighter-bombers were available to hit known gun positions on what proved to be the last opportunity to use air support before the weather curtailed operations. The artillery fired enough smoke shells to screen the advance from observed enemy fire, but enemy engineers had laid enough mines and explosive charges to slow down any advance. The lead tank on the left side of the road was “destroyed by a demolition charge of some 200 tons of TNT. The tank was lifted 20 feet in the air and landed on the other side of the road. All crew members were instantly killed.”

The other three tanks in the troop struck the minefield and lost their tracks without suffering casualties. Fortunately, the right flank troop was able to support the infantry and they were able to establish themselves at the south end of Ortona. They made contact with a company from the Seaforths that had fought its way along the coast road before strengthening its position by deploying a Saskatoon Light Infantry medium machine-gun platoon as well as a troop of six-pounder anti-tank guns. Surprisingly, the enemy decided not to counter-attack. The Eddies had taken 17 prisoners from the 4th Para Regt. and inflicted other losses on the enemy’s forward troops, but this time the German commander was determined to avoid the kind of counterattacks that had weakened the German battalions at the Moro River and the Gully.

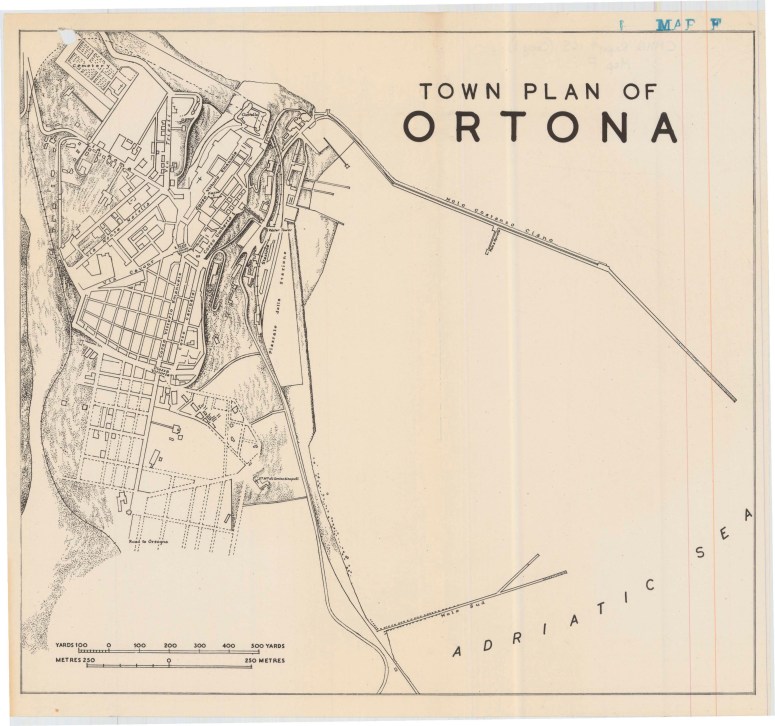

Historian Eric McGeer, the author of a battlefield guide Ortona and the Liri Valley, suggests visitors should follow the Contrada Santa Lucia, a road along the top of Vino Ridge, which was captured by the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry in the battle for The Gully. The road dips down into The Gully before joining the Orsogna-Ortona lateral road and it offers an exceptional view of the approaches to Ortona. During our visit to the area, a steady rain limited visibility. However, the problem presented by the natural defences of the town was readily apparent. Ortona sits on a promontory that is protected by deep ravines.

The Canadian battle group began advancing into Ortona at 7 a.m. on Dec. 21. The war diary of the Edmonton Regiment records the start of street fighting, noting that “the enemy is well supplied with machine-guns in dug-in positions behind stone barricades. Hand grenades are being used by both sides. Tanks are hampered by demolitions and mines, but they are providing covering fire….”

Lieutenant-Colonel Jim Jefferson, the commanding officer, divided the town into four sectors, numbered clockwise from the south. He hoped to seize control of both southern sectors, but resistance on the left was too strong so he reinforced success with tanks and infantry that managed to press forward to the first city square, the Piazza Porta Caldari, by nightfall. “Owing to casualties, the Loyal Edmonton Regiment reorganized on a three-company basis.”

Today, the wide street leading north from the square, the Corso Vittorio Emmanuele II, is a pedestrian avenue lined with fashionable shops. In December 1943, the enemy had turned it into a killing zone. The narrow side streets were blocked by rubble from demolished buildings. Snipers and machine-gun posts covered every approach, and anti-tank guns were positioned to fire down the side streets if tanks tried to advance with the infantry.

As the operational report noted, “no two houses were defended alike.” However, there were plenty of automatic weapons and grenades available to each section of enemy paratroopers. “Houses, which were not occupied, were booby-trapped or had delayed charges placed in them with time fuses.”

House-to-house fighting began in earnest on Dec. 21 and lasted until the town was clear a week later. On the morning of the 22nd, the Seaforths provided a company to support the advance by the Loyal Eddies. By afternoon, after the strength of enemy resistance became clear, Brigadier Hoffmeister sent the balance of the Seaforths into Ortona to take over the western part of the city. The next day–as the battle for Ortona intensified–the Hasty Ps attempted to “burst out” to the north along a “thumb-like feature that ran northeast towards the coast road north of Ortona.”

Brig. Dan Spry reported that the attack by the Hasty Ps struck “a whole German paratroop battalion, hitting the middle company and destroying it. They also took prisoners from other companies,” setting the stage for what the regimental history of the 48th Highlanders of Canada describes as “one of the most daringly conceived and executed one-battalion enterprises of the Canadian campaign–in either Italy or Normandy.”

The ground over which the 48th Highlanders advanced forms a narrow ridge between the valley cut by the Ricco River and the ravine forming the western rampart of Ortona. Their objective was the high ground opposite the village of San Tomasso, a feature that dominated the area to the north and west of Ortona. The padre of the 48th described the position as “cemetery ridge” because of all the casualties–German and Canadian–but on the afternoon of Dec. 23 it looked as if the 48th Highlanders had broken through the enemy defences without suffering a single casualty.

The day began with a “man-sized issue of rum with tea which tasted like Moro River mud as a chaser.” Delays in clearing the start line postponed H-Hour until late in the afternoon when the last light was fading from the December sky. Lt.-Col. Ian Johnston preferred to postpone the advance until first light, but Spry insisted “the attack had to be made at once–even in darkness.” The regimental history describes the scene: “The Highlanders were risking their survival as an effective fighting force on the factor of surprise. Everything was sacrificed to surprise–all their supporting arms and even their own anti-tank guns and mortars. They would take only Bren guns and grenades, their Tommy guns and rifles…. It just might succeed, if it did it would win Ortona.”

The battalion began to follow a footpath, picked out from an air photo. They moved silently–in single file–through a “vineyard tangle which was cut and criss-crossed by small ravines and gullies.” A steady rain and a loud firefight back at the start line slowed the advance until everything came to a halt. The lead company had reached a house occupied by German paratroopers. “With the quick silent reactions of raiding Mohawks, Major John Clarke and his picked men soundlessly killed one man outside the house, covered all exits and then leaped into the midst of a Nazi Christmas party.” Thirteen paratroopers were taken prisoner before the advance resumed. A second house yielded six more paratroopers and then, despite fears that the vanguard was well and truly lost, the objective was reached without a shot having been fired!

The battalion dug in after sending a large fighting patrol back towards the start line on a track that Johnston hoped might be used to bring tanks and support weapons forward. The patrol ran into a German battle group that was blocking the track, and was forced to return to Cemetery Ridge. The 48th Highlanders were isolated and on their own. An all-around defensive position was created and the vital link between a British field regiment and its borrowed Forward Observation Officer was tested.

On the morning of Dec. 24, the German commanders faced a difficult choice. The position on Cemetery Ridge gave the Canadians the opportunity to direct observed fire over a wide area. Within Ortona, the infantry, supported with great determination and skill by the Three Rivers tank squadrons, had seized two thirds of the town, and were preparing to clear the rest. It was surely time for the Germans to withdraw to a new defensive line a few kilometres to the north.

Instead two additional battalions were committed to battle, one in Ortona and a second directed at the Indian brigade fighting its way forward on the Canadian flank. The Edmonton war diary noted the changed situation in the entry for Dec. 24. “The enemy resistance stiffens, fresh troops reinforce the garrison, a flame-thrower is used against us…. House-to-house fighting continues in the very narrow lanes and streets while our artillery shells the coast road, the cemetery and targets on our left flank. Our three-inch mortars do very excellent work in close support of the riflemen. Seventy-five reinforcements arrive….”

The Seaforths also received a “large number of reinforcements” which were badly needed as “there had been no sign of the enemy weakening.” The Canadians were to spend Christmas Day locked in a grim struggle that seemed to have no end. A new and determined effort was required to liberate Ortona and seize ground that would shield the town from observed enemy fire.

Most Canadians know very little about the role their country men played in the liberation of Italy, but mention Ortona and many can recall something about the World War II battle for this small Adriatic port. The most powerful visual image is the photograph of the Christmas dinner served to the Seaforth Highlanders of Canada in the Church of Santa Maria di Costantinopoli.

The Seaforth’s commander, Lieutenant-Colonel Syd Thomson, was able to rotate his companies back to the church, where hot food was served and where Christmas carols were sung with the help of an organ. The Seaforth padre, Roy Durnford, recalled the scene: “The men looked tired and drawn, as well they might, and most of those who came directly from the town were dirty and unshaven. ‘Well,’ I said, ‘at last I’ve got you all in church.’ For the dinner there was soup to start then roast pork…. Christmas pudding and minced pies for dessert…the tables filled and emptied and were filled again all day, and I saw tense forces relax in the friendly warmth that grew up within the wall of the battle-scarred church…. Above the din one could hear sometimes the distant chatter of machine-gun fire and the whistle and cramp of shells landing not far from the church.”

Back at divisional headquarters, Charles Comfort, the Canadian war artist, and several friends walked over to the tent used by an Advanced Air Support Tentacle. Frustrated by the dismal weather that kept their aircraft grounded, the Royal Air Force officers “had tuned into the King’s Christmas message, delivered in his slow dignified style.” King George VI expressed the hope that his message spoken to those at home as well as those serving overseas “may be the bond that joins us all for a few moments on Christmas Day.” Afterwards, they listened to reports of continued fighting and the problems of mired tanks and limited supplies. There was a mess dinner that evening, enlivened by news of the Seaforth’s Ortona dinner, “an inspiring Christmas story…that filled us with abounding hope and encouragement.”

The Seaforths needed a bit of encouragement after their close-quarter battle on Dec. 24. German paratroopers had marked Christmas Eve with their first major counter-attack inside the city. On a front of less than 800 yards the Germans could bring enormous pressure to bear and much depended on the skill and determination of the section leaders and their men, isolated in houses or behind rubble piles. Thomson did his best to visit every position, “directing and co-ordinating the defence.”

Historian Reg Roy described Thomson’s role as an inspirational leader: “To see the commanding officer of a battalion at such a time somehow gave confidence to the private soldier, and Thomson’s unruffled calm and big smile acted like a tonic. His tactical skill, gained under fire as a platoon and company commander, was evident as he went from post to post to make sure his men, more accustomed to the attack than defence, had their weapons and fields of fire placed to the best advantage. The counter-attack was beaten back….”

While the Loyal Edmonton Regiment was spared the Christmas Eve counter-attack, there was no respite for the regiment’s rifle companies on Christmas Day. They were locked in combat at the Piazza della Repubblica and could not be withdrawn. Major J.R. Stone recalled that his Christmas dinner was “a cold pork chop brought forward on a Bren gun carrier.” His company had just fought an intense battle for a school that controlled the approaches to the square, known to the men as the Piazza Municipale. On Christmas Eve, a platoon working with a troop of tanks had found a route into the square that bypassed the rubble heaps that blocked most of the streets. In a superb example of infantry-tank co-operation, one side of the school was blasted down by a Sherman tank’s 75-mm gun while the other tanks provided suppressing fire. Sections of infantry entered the school, then cleared it using grenades and Tommy guns.

There were other examples of tactical victories in Ortona. Row houses were cleared from the top down using a technique the troops called “mouse-holing.” This involved breaching the walls of contiguous houses, and lobbing grenades through the hole before entering. Six-pounder anti-tank guns firing high explosives through windows or through blast holes also became a standard method, but there were no magic formulas.

Lieutenant-Colonel Jefferson described the situation confronting his men as a “vicious circle.” Once the infantry had seized a group of houses, sappers (engineers) moved up to clear mines and booby traps. Both infantry and tanks were needed to cover the sappers while they performed this dangerous work. Attempts to hurry things up by outflanking the enemy were especially difficult in the dense narrow streets, and the fighting resumed its old pattern–for one house at a time.

The attack on the Seaforth’s and on Jefferson’s “vicious circle” was the result of the enemy’s decision to send additional troops into Ortona, a decision German Field Marshal Albert Kesselring blamed on British General Bernard Montgomery and the Allied press. “The English,” he complained, “have made Ortona as important as Rome.” The town, he told his generals, was “not worth so much blood.” But, he added, it could not be given up. German General Richard Heidrich, who commanded 1st Para Division, was so confident reinforcements would prevent any further advance that left Italy to go on leave to Germany.

The enemy’s plan to stabilize the situation in Ortona was part of an overall attempt to check the advance of V Corps’ British and Commonwealth divisions. The battle for Villa Grande and the road to Tollo continued to bleed the Germans as well as the Indian Div. while a fresh paratroop battalion prepared to attack the 48th Highlanders of Canada, who were dug in on Cemetery Ridge. The ring of steel around the 48th Highlanders tightened throughout Christmas Day, and the regimental history describes the efforts of Private John Crockford, the commanding officer’s batman, to celebrate Christmas with a cake made from cornmeal, powdered milk and chocolate. He used his finger to trace the words Merry Christmas in the icing. Much later, when some of the wives of the 48th Highlanders asked what made the cake rise, the reply was that it didn’t.

The cake was the only cheerful note in a day of rain and shelling. Fortunately, the radio link with the artillery held and the Allied gunners were told to think of the position as an “island” and to just keep shooting at targets around the full 360 degrees. Brigadier Dan Spry wanted the Royal Canadian Regt. to advance through the 48th Highlanders’ position and cut the main road north of Ortona, but the reinforced enemy was too strong and instead the Canadians had to deal with the aggressive actions of the paratroopers, who substituted infiltration tactics and daring night patrols for conventional counter-attacks.

Spry next decided to try and establish a corridor to resupply what was dubbed the “lost battalion” using a company of the Saskatoon Light Infantry. Some 60 men, carrying food, water and ammunition, set off at dusk on Christmas Day. When they reached Cemetery Ridge, it was with “rations, wireless batteries, ammunition, a few extra Brens, two or three light mortars–and rum!”

Lieutenant-Colonel Ian Johnston sent a message with the Saskatoon Light Infantry carrying party, which headed back with prisoners and seven wounded stretcher cases. The message read: “Ask Spry to send us just one tank and we’ll massacre them.” Unfortunately, tanks could not get through the mud or the enemy so the 48th Highlanders faced Boxing Day alone.

A new German onslaught began at 10 a.m. Shelling and machine-gun fire, which was designed to keep Canadians in their slit trenches, was followed by an attempt to rush the defences with “two strong groups linked by skirmishers.” After three days in place, the 48th Highlanders knew every inch of ground and had sited their Bren guns to cover all approaches. Though the enemy suffered heavily, it kept coming, infiltrating between the positions and forcing hand-to-hand clashes. Company Sergeant Major Gordon Keeler saved his company headquarters from being overrun by hurling grenades from an upper window before rushing into the action below. The artillery forward observation officer used a single gun to ensure accuracy and brought its fire down within yards of the Canadian position. The enemy withdrew, regrouped and tried again, but the 48th Highlanders held.

A gradual drop in temperature throughout the day began to solve the mud problem and the battalion intelligence officer, Lieut. John Clarkson, was sent back to the RCR position to lead a troop of Ontario Regt. tanks forward. Three of the four tanks made it through just in time to help overwhelm a company of enemy paratroopers forming up for yet another attack. The tanks turned a defensive victory into a rout as the enemy withdrew in some disorder, setting the stage for an advance to the coast.

Boxing Day in Ortona was equally dramatic. The best news was the arrival of reinforcements for both the Loyal Edmonton Regt. and the Seaforths. The draft sent to the Edmonton Regt. had been drawn from the Cape Breton Highlanders, one of the infantry battalions in the newly arrived 5th Canadian Armoured Div. Jefferson is said to have greeted them with the words: “You are now A Company.”

The day was also marked by tragedy. An Edmonton platoon seized a building the Germans had wired with heavy explosive charges. The explosion buried the men and the sole survivor was entombed for three days until he was rescued after the battle. Retribution was swift. A building that the enemy was tricked into occupying was blown up, accounting for some 20 paratroopers.

The ferocious struggle in the streets of Ortona came to an end on the night of Dec. 27 with the sudden disappearance of the enemy. A battle that the Germans thought they could win was transformed by the determination of the Canadians in Ortona and the threat posed by 1st Canadian Infantry Brigade, which was now operating with full squadrons of the Ontario Regt. General Herr, the German corps commander, decided enough was enough. His units were “wasting away” with little purpose, and he authorized a limited withdrawal to a line hinged on the Torre Mucchia, Point 59, north of Ortona. These were positions that would still allow him to deny the Allies use of the town.

Lieutenant-General Sir Charles Allfrey, who commanded V British Corps in which the Canadians served, had little choice; he ordered the Canadians and 8th Indian Div. to force a further German retirement. Vokes brought 3rd Canadian Infantry Bde. forward with orders to capture Point 59 and clear the ground to the Arielli River. The attack began on Dec. 29 and immediately ran into difficulty. Today’s visitor to the area knows Point 59 the Torre Mucchia, as the hill rising above the beachfront hotels of the Lido Riccio. In 1943, there was little there except a few farmhouses surrounded by vineyards and olive groves. The Riccio River, a small creek by Canadian standards, parallels the coast before turning to the sea at the Torre Mucchia.

Third Bde. had received more than 400 reinforcements and had been in reserve since the Casa Berardi battle. However, those relatively fresh troops found the task of clearing the gullies along the Riccio to be a costly and exhausting enterprise. The Carleton and York Regt.’s attempt to storm Point 59 broke down when the two forward companies were struck by accurate artillery and mortar fire. The paratroopers held Point 59 in strength, forcing the regiment to dig in. The Royal 22nd Regt. was more successful, reaching a spur on the far bank of the Riccio, but it too was forced to go to ground in another exposed area.

Further attempts to force an enemy withdrawal were interrupted by a ferocious storm that was to stand as a metaphor for the end of one year of bloodshed and the beginning of a new year of savagery. The enemy, offering a forecast of what was to come, spent the last hours of 1943 in making a savage counter-attack that burst through the two forward companies of the Carleton and York Regt.

The situation was restored, but in the water-filled slit trenches exhausted men could do little more than hold on. Point 59 finally fell on Jan. 4 after one of the most extensive artillery programs of the campaign. Both medium and heavy guns joined the Canadian field regiments in a barrage that continued from early morning to late afternoon. When the Carleton and York Regt. attacked, both Point 59 and the beaches behind it were quickly cleared. The capture of the Torre Mucchia marked the end of the offensive operations that had begun at the Sangro River. All across the front the divisions of V British Corps reorganized to hold ground rather than attempt a further advance. The Eighth Army’s Adriatic offensive was over.

Ortona: Postscript

General Bernard Montgomery’s “colossal crack” of December 1943, an advance by Eighth Army to Pescara and the lateral road to Rome, was intended to outflank the enemy positions at Cassino. By late December it was evident that these operations had stalled. The battles fought “in a sea of mud” under the most miserable conditions were consuming Eighth Army, which had suffered more than 10,000 battle casualties. Losses from sickness and battle exhaustion were also very high, imposing an incredible drain on available human resources.

Canadian casualties totalled 176 officers and 2,163 other ranks, killed, wounded and missing, including the 650 casualties suffered during the fighting for Ortona. The 8th Indian Division was in even worse shape, having lost 3,400 men in a little over four weeks of combat. The New Zealand Div., with just two infantry brigades, reported 1,260 casualties, 72 per cent in its six infantry battalions. Losses categorized as sickness, which included battle exhaustion, added thousands more to the toll. It was time for Montgomery to follow Caesar’s wise example and “go into winter quarters.”

Conditions and casualty figures in Gen. Mark Clark’s Anglo-American Fifth Army were similar. After the difficult struggle to hold the beachhead at Salerno and the liberation of Naples, Oct. 1, 1943, Fifth Army was a spent force in need of rest and reinforcements. When Clark’s divisions were able to renew the advance, they confronted a well-organized, powerful enemy holding the Volturno River just 56 kilometres north of Naples. The Volturno, like the Sangro and Moro rivers on the Adriatic coast, was transformed into a swollen river with the beginning of the winter rains. After a bitter, costly battle, the enemy withdrew to the Gustav Line, using the Liri, Gari and Garigliano rivers to link Cassino with the coastal mountains and Tyrrhenian Sea. To armchair strategists, especially Prime Minister Winston Churchill, the solution to this problem was to mount a second large-scale amphibious landing behind German defences. Clark’s staff began planning the operation on the assumption that such a landing could only take place if Fifth Army had previously broken through the Gustav Line.

Operational realities soon became less important than a debate about resources for the Italian Campaign. The British had reluctantly agreed to send troops and most of the scarce Landing Ships, Tanks (LSTs) to England in preparation for Operation Overlord and D-Day. They now sought and won a postponement of the LST transfer so that a landing at Anzio, south of Rome, could take place in early 1944. Clark recommended that all offensive operations–including Shingle, the codename for landings at Anzio–be called off until spring, but Churchill was insistent. He, and the British Chiefs of Staff, had used a good deal of their political capital persuading the Americans to agree to one more amphibious attack in Italy, so there had to be one.

Operation Shingle was now to be a two-division assault on the German flank that “would open up the way for a rapid advance to Rome.” It was scheduled for Jan. 23, 1944, two days after a new assault on Cassino and the Gustav Line began. Those who argued that the Germans had sufficient troops to contain an attack on the scale of Shingle without weakening their defences in the south were ignored, despite solid intelligence of German dispositions. Major-General John Lucas, who was to command Shingle, complained that “the whole affair has a strong odour of Gallipoli and apparently the same amateur (Churchill) is still on the coach’s bench.”

Eighth Army, now commanded by Lieutenant-General Oliver Leese, was to play a minor, purely holding role in the new offensive. Leese, who had commanded XXX Corps in North Africa and Sicily, had been sent home on leave because of growing problems with his “nervous disposition and temperament.” Appointing an army commander who had no direct experience of the intense battles of November and December was a curious decision, particularly since Montgomery was also “skinning a lot of his people” out of Italy for Overlord, including Lt.-Gen. Miles Dempsey, the most experienced corps commander, and Air Vice-Marshal Harry Broadhurst, the senior air officer.

Leese, his army reduced to two corps, ought to have been pleased to learn that the 5th Canadian Armoured Div., together with the headquarters of I Canadian Corps, had arrived in Italy. Instead, he echoed Montgomery’s view that neither an armoured division nor an inexperienced corps headquarters was needed. When he heard that Lt.-Gen. Harry Crerar would shortly return to England for Overlord, Leese complained that “Crerar knows nothing of military matters in the field…so I have to teach Crerar for a time and then change to another totally inexperienced commander.”

Leese shared the common Eighth Army view that no one but a veteran British general ought to command at the corps or army level. These sand-in-their-shoes officers were condescending to everyone–American, Canadian and British–if they had not fought with Montgomery’s Eighth Army in the desert. The Americans, with their own self-confident sense of superiority, were unimpressed by the British Army, which they saw as overcautious, but most Canadian officers accepted the Eighth Army mystique and sought to win approval rather than to assert their own identity.

There was, of course, an obvious case against sending additional Canadian formations to Italy at a time when British and American troops were returning to play a part in the invasion of France. It was J.L. Ralston, Canada’s minister of national defence, who pressed for the establishment of a Canadian Corps in Italy. A Great War veteran who had persuaded his cabinet colleagues to agree to a five-division army for Europe, Ralston believed that the war might end in 1944 with few Canadians having seen action.

Lieutenant-General Kenneth Stuart, the Canadian Chief of Staff, accepted Ralston’s plan and overcame the opposition of Gen. Andrew McNaughton, who wanted 1st Division back in England–not a further dispersion of the Canadian Army.

One of the many problems created by Ralston’s decision was the equipment question. Shipping space could be found for 25,000 troops, but there was no room for trucks, tanks or artillery. Only personal weapons could be carried. The armoured brigade was supposed to be re-equipped with what 7th Armoured Div. was leaving in Italy, including a great many worn-out armoured vehicles. Crerar and Maj.-Gen. Guy Simonds, who was given command of 5th Armoured in preparation for his promotion to corps commander, ended up spending most of their time in Italy ensuring that the division and corps troops got the best possible weapons and equipment before they entered battle.

While the armoured brigade and the 10,000 corps troops, including medium and field artillery, anti-tank, armoured car, anti-aircraft, engineer, ordnance, service corps and medical personnel, re-equipped and began retraining, the 11th Canadian Infantry Bde. was assigned to a very different role. The brigade, composed of the Perth Regiment, the Cape Breton Highlanders, the Irish Regt. of Canada and the 11th Independent Machine Gun Company (the Princess Louise Fusiliers), was sent north to the Ortona salient to allow the 1st Div.’s weary battalions to withdraw for rest and reinforcement. Brigadier George Kitching, who had served as senior staff officer (GSO1) in 1st Div., was given command of the brigade for what became known as the Arielli Show.

When 1st Div. abandoned the offensive north of Ortona in early January, it dug in to defend a narrow salient anchored on the Adriatic coast that slanted back to Villa Grande, the furthest point reached by 8th Indian Div. First Parachute Div., held the high ground between the Riccio and Arielli rivers with good observation over the Canadian positions. This was exactly where the senior Allied officers wanted the paras to remain while the landings at Anzio and the battle for Cassino got underway. Leese knew that Eighth Army, weakened by the transfer of divisions to participate in the main offensive, could do little to persuade the Germans that a new Adriatic offensive was imminent, but he insisted that “all ideas of a static or low-priority front… must be eradicated from everybody’s minds.” The New Zealanders were to make yet another attempt to gain Orsogna after the Canadians made “every effort to gain the high ground east of the River Arielli.” This was to be done with all available artillery but “without incurring heavy casualties.” Leese had no practical advice as to how such an attack could be carried out without heavy casualties.

According to Kitching, who described the Arielli Show in his memoirs, Mud and Green Fields, the corps commander, Lt.-Gen. Charles Allfrey, “seemed to think he should plan my brigade battle.” The elaborate fire plan, handed down from corps, required 11th Bde. to attack on a narrow, one-battalion front. The Perth Regt. was to lead off, with the Cape Breton Highlanders (CBH) responsible for the second phase. The initial artillery bombardment included one heavy, five medium and nine field regiments, and included a lifting barrage for the Perth Regt., as well as counter-battery fire, concentrations in likely enemy positions and smoke to blind German observers directing their artillery. Kittyhawk fighter bombers added to the weight of high explosives directed at the enemy.

The 12th Canadian Armoured Regt. supported to 11th Bde. and Lieutenant-Colonel E.L. Booth tried to provide “maximum tank support” to the green troops carrying out their first attack. “A” Squadron, assigned to the Perth Regt., towed the infantry’s six-pounder anti-tank guns forward and worked out tactical details with Lt.-Col. Rutherford and his company commanders. The Canadian Army was committed to a “lessons learned” approach to training, and 1st Div. had offered its advice on how to fight a set-piece battle after Ortona. There was nothing new to say about tank-infantry co-operation except to argue that “each arm must thoroughly understand the possibilities and limitations of the other.”

This was not an easy task. Booth explained that the tanks could not go forward with the initial infantry thrust because of anti-tank mines. The tanks would instead take up positions on the crest of the ravine overlooking the river to take on known and possible enemy positions with direct 75-mm and machine-gun fire. When the Perth Regt. attack bogged down at the river crossing, the tanks were sent forward to assist the infantry and engineers, even though it was pre-registered artillery and mortar fire that had stopped the Perth Regt. The same problem confronted the CBH and, once again, tanks were called for. The lead troop lost one tank to a mine and a second to an artillery shell.

Later in the afternoon, the Perth Regt. and 12th CAR were able to cross the river and establish themselves on the reverse slope due to a heavy counter-battery shoot that temporarily silenced the German guns. By midnight, losses to 11th Bde. amounted to 185 men, 130 of them from the Perth Regt., and Allfrey decided to order the brigade to withdraw under cover of darkness. The Germans dismissed the Arielli Show as a diversion and claimed to have eliminated the “temporary penetration” by a counter-attack. Their program for transferring artillery units to the Cassino front went ahead on schedule.

The 11th Bde. had been “blooded” and could now claim battle experience, but the cost was far too high. On Jan. 23, the brigade took over the Orsogna front vacated by the New Zealanders, who had moved west to join Fifth Army’s offensive at Cassino. Heavy snow and rain plagued the soldiers as slit trenches–dug into saturated ground–quickly filled with water. The Germans still held the town and ridge line overlooking the brigade positions, using the tall church tower in Orsogna as an observation post until the tanks of the Lord Strathcona’s Horse demolished it.

While 11th Bde. settled into the Orsogna sector, 1st Div. returned to the Arielli under orders to maintain pressure while absorbing the large numbers of reinforcements that had come forward. Evidence of the transfer of German units to meet Fifth Army’s offensive led the corps commander to order another attack across the Arielli. Allfrey described the task as a “holding attack” designed to draw enemy reserves, but insisted “that the real purpose of the venture should be kept from the participating troops.” The Hastings and Prince Edward Regt. and the Calgary Tank Regt. drew the assignment, which produced more than 90 casualties and not much else. No further battalion-level attack was ordered at the Arielli because I Canadian Corps was now slated to take part in a spring offensive in the Liri Valley.