The Devil’s Brigade

Italy, Normandy’s ‘Long Right Flank’, was the theme of University of New Brunswick historian Lee Windsor’s keynote address to the 18th Annual Military History Conference at Wilfrid Laurier University in Waterloo, Ont. Dr. Windsor, a passionate and compelling speaker, made the case for evaluating success or failure in Italy in terms of the impact of Allied operations on German priorities. Since Hitler was forced to use some of his best divisions to hold a series of defensive lines in central Italy, the Allies, he argued, accomplished their purpose by weakening Hitler’s capacity to defend the coast of France and prevent the breakout from Normandy.

Dr. Windsor’s interpretation of the significance of the battles for Rome and the assault on the Gothic Line harkens back to Dwight D. Eisenhower’s oft-quoted telegram to Winston Churchill, dated Oct. 25, 1943, which stated: “It is essential for us to retain the initiative until the time approaches for mounting Overlord… If we can keep him on his heels until early spring then the more divisions he uses in a counter-offensive against us the better it will be for Overlord and it then makes little difference to what happens to us if Overlord is a success…”

This view of the Italian Campaign correctly explains both the strategic purpose and larger achievement, but it does not resolve questions raised about specific operations carried out by Allied armies. At the theatre level, General Alexander–the army group commander–and his senior subordinates, generals Oliver Leese and Mark Clark, appear to have sought great victories; breakthroughs and breakouts that would transform Italy from a holding action into a decisive theatre of war. This attitude, which was shared and encouraged by Churchill, was especially evident in Clark’s Fifth United States Army, a multinational force that included three British and two French divisions as well as five from the U.S. Army.

Clark rose from obscurity as a junior staff officer to lieutenant-general and Fifth Army commander in 1943 without any experience in combat at battalion, regimental or divisional level. The noted American military historian, Martin Blumenson, has described him as “Aggressive, impatient, imperious in bearing and inclined to be sharp of tongue, although he could be elegantly charming.” These characteristics were coupled with an over-confidence in his own judgment of operational possibilities.

Clark’s army was to strike north through the Liri Valley to Frosinone, 90 kilometres south of Rome, while Eighth Army fought its way to Pescara and the Valerian Way, the east-west road to Rome. When the two armies reached these objectives, Alexander would launch a seaborne landing at Anzio–on the coast south of Rome–that was designed to cut off the enemy facing Fifth Army.

There were a number of problems with this plan. The weather in November and December was likely to be rainy with snow in the mountains. The terrain, mountainous country with fast-flowing rivers cutting across the battlefield, favoured the enemy. The force ratios, attackers to defenders, came nowhere near the 3:1 odds considered necessary for success. Through Ultra, Alexander and his two army commanders knew Hitler was determined “to defend central Italy on the line Gaeta-Ortona” with his Tenth Army, while the Fourteenth Army defended the coasts and “pacified” the north.

Albert Kesselring, Hitler’s supreme commander in Italy, had ordered XIV Panzer Corps to hold the mountains on either side of the Mignano Gap, blocking the approach to the Liri Valley. During November when Fifth U.S. Army was reorganizing, German engineers supervised the laying of minefields and well camouflaged machine-gun and mortar positions. Deep dugouts “roofed with tree trunks, planking and sandbags” were connected to the firing posts by crawl trenches. When necessary, solid rock was excavated to provide the necessary cover.

On the plus side, the Allies knew the German Army was in the midst of a major reorganization intended to save manpower by reducing the size of a division from roughly 17,000 men to 13,000. All three divisional infantry regiments lost a battalion, but a fusilier battalion, often employed as the divisional reserve, as well as powerful artillery and anti-tank battalions were preserved. This sustained the combat power of the division in defensive operations–the only kind required in Italy.

The German Army was also thought to suffer from shortages, especially in artillery shells, but those with front-line experience knew that German gunners, with full observation over the battlefield and time to register targets for artillery and mortars, had no need of the extensive barrages employed by the Allies to neutralize the enemy during an attack. With the mountainous terrain as a force multiplier, the seven and one-half German divisions of XIV Panzer Corps were a formidable obstacle.

As always, the Allies hoped air power would make up for other deficiencies, and the newly organized Mediterranean Air Command was prepared to offer considerable support. When the advance towards Cassino and the Liri Valley began on Dec. 1, overcast skies and frequent days of heavy rain–normal for central Italy in December–limited the impact of air superiority.

Clark divided the operation into three phases “so that the maximum air and artillery support can be used against the most difficult terrain.” Phase I required the capture of the “critical terrain features” Monte Camino, Monte la Difensa and Monte Maggiore. This task was assigned to 56th British Div., which had already tried and failed to capture the position, and a fresh U.S. division, the 36th, which had been strengthened by the attachment of the First Special Service Force, the so-called Devil’s Brigade.

Jim Wood, the author of We Move Only Forward, the most recent history of this remarkable unit, the only joint Canadian-American formation created during World War II, notes that the brigade was originally developed to operate as elite troops “trained in winter warfare and equipped with armoured snow vehicles, and capable of either parachute or glider landings in the snow-covered regions of occupied Europe…these highly trained troops would be able to conduct long range sabotage operations against key industrial targets.” This outlandish project, known as Operation Plough, was inspired by Mountbatten and his eccentric science adviser Geoffrey Pike. Wood offers a balanced review of the politics behind the project as well as the recruitment and training of a force that was eventually employed in the unopposed landing at Kiska in Alaska.

The transfer of FSSF to Italy in September 1943 was accomplished without any decision on what role a highly trained, lightly armed “commando” unit might play. The force was comprised of three “regiments,” each of two, two company battalions and one administration battalion. The total strength, roughly 2,200 officers and men, included 600 Canadians concentrated in the combat battalions. Since the force had been created to carry out a single mission, no provision had been made to provide trained reinforcements. The 60-mm mortar was the heaviest support weapon. The force brought 600 of the small, tracked-carriers–known as Weasels–with them to Italy, though it was by no means clear what value the machine’s ability to operate in snow might have.

Eisenhower had requested the FSSF “for special reconnaissance and raiding operations” but Clark decided to use them as regular infantry providing a battalion of airborne artillery to increase their hitting power. The FSSF commander, Colonel Robert Frederick, reported to the 36th “Texas” Div. on Nov. 23. So, there was less than a week available to prepare for their assigned task capturing Monte la Difensa.

The Camino-Difensa-Maggiore massif is a formidable sight. Little has changed since 1943. The lower slopes are terraced with olive groves, but the northeast face of Monte la Difensa, the route followed by Col. Don Williamson’s 2nd Regiment, becomes close to vertical one third the way up. Williamson, a Canadian officer, used the 1st Battalion to lead the way with light, climbing loads while the 2nd Bn. followed with enough food, water and ammunition to hold the position they hoped to seize. The artillery program–925 guns and 22,000 shells, which seemed so impressive to observers –did little damage to the well-fortified defenders. And so the initial success–achieved by climbing the most difficult approach route–soon evaporated. Monte la Difensa was held by a battalion-sized battle group, supported by heavy artillery and the hated Nebelwerfer. Initially, the defenders were cut off and with little hope of withdrawal fought for “six cold bloody days” in a battle of extraordinary ferocity. By Dec. 8, when German resistance ceased, the FSSF had suffered 511 casualties, including 73 dead and 116 hospitalized for battle exhaustion.

The decision to employ this elite force in such an operation meant that the reinforcement question could no longer be avoided. American replacements could be drawn from Fifth Army’s pool with FSSF officers combing the ranks for the best men. No Canadian reinforcements were available. Before this issue or the training and integration of replacements could be dealt with, the Corps commander, General Geoffrey Keyes, sent the force back into action at Monte Sammucro. On Christmas Day, the 1st Regt. began a frontal assault on a German position, “encountering strong enemy opposition.” Success was obtained, but at the end of the day the effective strength of the regiment was 14 officers and 217 men, less than half its authorized numbers.

And there was no let up. The War Diary of the First Canadian Special Service Bn. includes the following entries: “Jan. 8: Today’s casualty return…lists 100 names, half of them frostbite and exposure, the rest battle casualties. The weather in the hills is very cold, with high wind and snow. German resistance is quite severe, artillery and mortar fire is taking its toll.

“Jan. 9: Today’s Force casualty return has 122 names, again nearly half are frostbite and exposure. There soon won’t be much left of the force if casualties keep up at this rate.

“Jan. 10: News from the front is bad…. The Force is being thrown into one action after another with only a handful of able-bodied men left and no sign of their being relieved. Seventy-three names on today’s casualty report, 40 frostbitten feet. Those returning to camp on light duty say it is really rugged and they are all played out. Three weeks tomorrow since they left here.”

No one could doubt that the FSSF had met the challenges of combat in the mountains of Italy. Under some of those most difficult conditions of weather and terrain the force had ably assisted 36th Div.’s conquest of the Camino massif. But what was an elite, paratroop trained, lightly armoured, under-strength special service force doing fighting an attritional infantry battle?

Aware of the fact that “less than half of the Canadian contingent” was still on its feet, and that there were no Canadian reinforcements available, the senior Canadian officer, Lieutenant-Colonel Thomas Gilday, recommended that the Canadian element be withdrawn from the FSSF while there was “still enough of it left to be of assistance to the Canadian Army. This withdrawal should take place immediately before the Force is committed again….”

Gilday feared that the Canadian component would be so diluted that the force’s Can-Am character would disappear as American reinforcements arrived. The problem was that Canadians filled many of the officer and non-commissioned officer ranks in all four combat battalions, and their departure would cripple the command structure. The battalion war diarist summed up the situation in his last entry for 1943: “This ends another year. It has been a very eventful one for the Force which covered a good 20,000 miles during the past 12 months, a long way before getting into real combat and at that finds itself in a definitely secondary theatre being used as glorified infantry and all the special training going by the birds except possibly for mountain climbing. The question that can only be answered in the New Year is ‘Will the Force be permitted to peter out here, which it is doing rapidly, or will it be employed in a new theatre where some of its specialized training can be used to advantage?’”

Before any action to withdraw or reinforce the Canadian contingent could be taken, Clark ordered the force to move to the Anzio bridgehead to defend a 10-kilometre sector along the Mussolini Canal. Employing the FSSF in an assault infantry role in the mountains might be justified, but canal defence on the edge of the Pontine Marshes? For Clark, the force was just another unit that could be used to fill a gap and for the next 98 days they experimented with aggressive defence, employing fighting patrols and blunting German counter-attacks.

A decision to reinforce the Canadian component from volunteers waiting in the Canadian reinforcement camps restored the Can-Am nature of the force in time for the breakout and the advance to Rome in May-June 1944.

Breaking The Gustav Line

If we are to understand the ferocity of the battles for Cassino and the approaches to Rome we need to recognize the depths of Hitler’s commitment to blocking an Allied advance in Italy. When Hitler ordered the occupation of Italy and the disarming of the Italian forces he decided to get as much out of Italy as he could “without regard to emotional ties” to Mussolini and the Fascists. The industrial capacity of northern Italy and its agriculture were absorbed into the German war economy and the labour force mobilized to assist the German forces. Labour unrest and partisan resistance were brutally suppressed.

One of the most extraordinary measures undertaken in the defence of German-occupied Italy was a deliberate attempt to create an epidemic of malaria in the Pontine Marshes south of Rome. The draining of the marshes and the construction of the Mussolini Canal was one of the great achievements of pre-war Italy, but the area now occupied a strategic position and in October 1943 the order was given to stop the pumps that drain the marshes. Two German scientists, experts on malaria, were sent to Italy to advise engineers on how to maximize breeding grounds for the most lethal mosquito species, and the plans to accomplish this were implemented once the Allied advance on Rome was underway. This dreadful experiment in biological warfare had little impact on the Allies who quickly crossed the Pontine Marshes before the malaria season was underway. Thereafter, the Allies employed massive amounts of DDT to safeguard their supply lines. It was the local population returning to their ruined homes and fields that had to endure “one of the great malarial upsurges in modern Italian history.”

Hitler also ordered the Todt Construction Organization, supplemented by conscripted Italian labour, to build formidable defences along a series of lines south of Rome. The Gustav Line, linking Monte Cassino with the sea, was built to take advantage of the Garigliano and Gari rivers. The Hitler Line was strengthened with concrete pillboxes and Panther turrets that were spaced to provide overlapping fields of fire for the high velocity 75-mm guns.

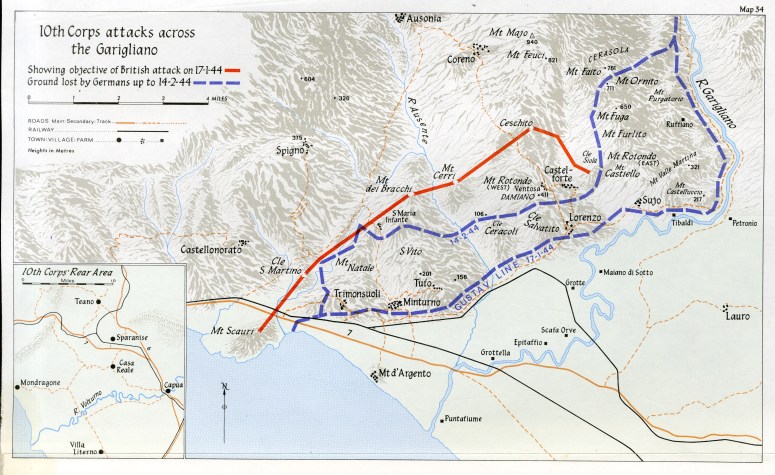

The Allies had abandoned the idea of an amphibious landing to outflank these defences because the necessary Land Ships Tank or LSTs were scheduled to leave the Mediterranean for Overlord. Churchill, who complained that the “stagnation of the Italian campaign was becoming scandalous,” won agreement to postpone the LST transfer, reviving the plan to land a force at Anzio, south of Rome. This “two division plus” operation was a risky venture so Allied planners assumed that the rest of Fifth Army would break the Gustav and Hitler lines to reach Anzio within 28 days. On 17 January, 72 hours before D-Day for Anzio X British Corps crossed the Garigliano River, the western bastion of the Gustav Line. Attempts to expand the bridgehead were checked by German reinforcements from the Rome-Anzio area. A further attempt to break through the defences by the 36th Texas Division ended in one of the worst tactical defeats of the war with more than 2000 American casualties.

Anzio was becoming one of the most bloody Allied operation of the European war with a monthly divisional wastage rate (killed, wounded, missing, prisoners of war, sick, injured, battle exhaustion) of 96 per cent–three times the average for Italy.

The crisis at Anzio called for new attempts to gain control of Cassino and the entrance to the Liri Valley. Alexander decided to strengthen Fifth Army, creating a New Zealand Corps under General Bernard Freyberg as an “exploitation force.” However, its first task was to win control of Monte Cassino and the town. Freyberg assigned the 4th Indian Div. to the mountainous approaches to the abbey where the French Expeditionary Corps had established a foothold. They were supposed to capture the monastery then pour down the mountain to help the New Zealand Div. seize the town.

Anyone who has walked the ground will understand the pessimism that threatened to overwhelm the troops moving into position for the attack. Eric McGeer’s battlefield guide to Ortona and the Liri Valley uses Google Earth satellite imagery as the base for his maps, and the view of Monte Cassino and the Liri Valley–looking towards Rome–offers a stunning visualization of the battle area for those who have not been to Cassino. None of this impressionistic information fully explains the decisions to destroy the monastery by bombing, but it may help us to understand why every soldier who has fought at Cassino was relieved when “the great white building that dominated the whole scene in that valley of evil memory” collapsed into ruins.

Unfortunately, the monastery was just a metaphor for the strength of the German defences and the February assaults failed to achieve their aims. A month later, the New Zealand Corps was ordered to make yet another attempt to secure Cassino and Monastery Hill. This time the town was to be destroyed with 1,000-pound bombs fused “to permit penetration of buildings down to basement depth.” Despite, or because of the bombing, the cratered ruins could not be cleared and held. As one anonymous New Zealander explained, “we are known as Kiwis because like the bird we can’t fly, we can’t see and we are rapidly becoming extinct.”

By the end of March 1944 these frustrating and costly operations were ended to allow the exhausted troops time to rest and recover. A new offensive, timed to prevent the Germans from reinforcing Normandy once Operation Overlord began, was to be launched in early May and this would require extensive preparation.

If the spring offensive was to succeed without the kind of favourable force ratio required by the terrain and fixed defences, something had to be done to block German reinforcements and re-supply. The Mediterranean Allied air force proposed to accomplish this through an independent air interdiction campaign with the evocative code name of Operation Strangle. Air attacks on roads, railway lines, bridges and marshalling yards north and south of Rome began in mid-March and continued until Diadem–the code name for the spring offensive–began. Despite considerable tactical success, Strangle failed to halt the flow of supplies, though it is credited with limiting German troop mobility. Unfortunately, for the Allied armies the German divisions manning the Gustav Line were not going anywhere unless overwhelming force was applied.

Alexander’s new plan called for the transfer of most of Eighth Army to the west. The British corps from Fifth Army was to be brought under General Oliver Leese’s control. Leese would now command two British corps plus the Polish, New Zealand and Canadian corps. Diadem was to involve 11 divisions rather than the two or three used in earlier attempts against the Gustav Line.

Leese placed the Canadian Corps in reserve to tackle the Hitler Line, but he ordered 1st Canadian Armd. Bde. to work with 8th Indian Div. in the battle for the Gari River bridgehead. Major Michael Boire, a history professor at the Royal Military College, is researching the history of this often overlooked brigade and its three armoured regiments. Boire, an officer in the 12e Régiment blindé, has a special interest in 12th Canadian Armd. Regiment, a bilingual unit known in World War II as the Three Rivers Regt., but he also is evaluating the battle experience of the Ontario and Calgary regiments together with the role of brigade headquarters.

It is evident that 1CAB under Brigadier Bob Wyman and his successor Bill Murphy, as well as the commanding officers of the individual regiments, embraced the infantry-support role assigned to them, putting aside their dreams of brigade-level tank actions. The Three Rivers Regt., committed to action in Sicily and Termoli well before the rest of the brigade was involved in the battles for the Moro River and Ortona, led the way in tactical development, but all three regiments used the first four months of 1944 to train and absorb lessons learned. By May 1944, 1CAB, the most effective armoured brigade in Eighth Army, was in demand everywhere.

Major-General Dudley Russell, the commander of 8th Indian Div., issued his orders for the Gari crossing well ahead of time, allowing the Ontario and Calgary regiments to work closely with the 17th and 19th infantry brigades. The Three Rivers Regt. was tasked to support the 21st Bde. in reserve for an exploitation role. Every detail of a very complex operation was worked out–“no one seemed to be rushed and everyone knew exactly what was required of him.”

The plan called for the rapid consolidation of a bridgehead so that engineers could construct a series of bridges across the river. Without armoured support the infantry would have trouble surviving counter-attacks or seizing control of the heavily fortified positions on the high ground beyond the river. The flexibility of the armoured brigade was evident in the preparations to support the assault battalions from the riverbank and in the remarkable experiment carried out by Captain H.A. Kingsmill and the Calgary Regt. Kingsmill, an ordnance corps officer attached to the Calgaries, supervised the creation of a tank-launched Bailey bridge. In collaboration with a company of Indian engineers, rehearsals were held and during the night of May 11-12 the bridge–mounted on a turret-less Calgary tank equipped with rollers, and with a pusher tank behind–reached the river. The first tank, guided by Kingsmill and two Bengal sappers, entered the river to serve as a pier, and its driver escaped as it submerged. The bridge was nosed onto the far bank. Kingsmill–awarded the Military Cross for his efforts–was wounded by shellfire.

Canadian tanks and men move up towards the Gari River (also known as the Rapido) bridgehead, May 1944. IWM MWY 87.

The attack began with a massive counter-battery and counter-mortar program that helped to suppress the enemy’s indirect fire. However, the 1,000-metre-wide flood plain was studded with trip-wire activated mines and well concealed machine-gun posts. According to the Indian Army official history, “A cold damp mist lay over the valley. To thicken the mist and the clouds of dust and smoke rising from the artillery concentrations, the Germans ignited smoke canisters… visibility was no more than two feet.”

The 17th Indian Bde., responsible for the crossing on either side of Sant Angelo–the most heavily fortified part of the Gustav Line–was assisted by tanks of the Three Rivers Regt. whose crews had registered their machine-guns to neutralize enemy posts on the far side of the riverbank. The assault battalion groped its way forward, up against mines as well as enemy machine-guns firing on pre-arranged fixed lines. Despite heavy losses, the infantry secured a narrow bridgehead, and at first light the Calgary and Ontario regiment tanks began to cross.

The battlefield is little changed and a tour of the crossing points inspires admiration for the men who were confronted with fire from the village of San Angelo and the low ridge the troops called the Platform. The 3/8th Punjab Regt. found itself in front of German positions where hand grenades were rolled down the slopes to burst among the Indian soldiers. “A 19-year-old, Kamal Ram, new to the battalion and fighting his first action, attacked two German machine-gun posts single-handed.” He was later awarded the Victoria Cross.

Ontario Regt. tanks began crossing the river at 9 a.m., but “the flat ground on the far side of the river was found to be soft and boggy and 15 tanks bogged down. Men worked all day under constant shellfire to recover these tanks. The remaining force reached the lateral road and turned north to join the Gurkhas who were trying to mount an attack on Sant Angelo. They were able to link up with the Gurkhas and the next morning one Sherman led the Gurkhas in the assault on the village. By the afternoon of May 13, a “scissors bridge” had spanned the obstacle and an Ontario squadron moved through San Angelo to assist a battalion pinned down north of the village.

The Calgary Regt., supporting the 19th Indian Inf. Bde., was also slowed by the mist and soft ground, but the first tanks to reach the lateral road turned south shooting up enemy positions. “All during the afternoon the infantry made valiant efforts to get up onto the high ground and join the tanks. However, every time they moved they were cut to pieces by the continuous mortaring….” The next morning a second, full, squadron of Calgary Tanks and the reserve battalion, Royal Frontier Force Rifles, crossed the river. The RFFR and the Punjabs–supported by squadrons of the Calgaries–followed a heavy artillery barrage forward and reached the village of Panaccioni by late afternoon.

The Three Rivers Regt. and two battalions of 21st Bde. crossed into the bridgehead on the night of May 13 to lead the breakout. “The going was very hard. The morning was foggy, and the rough, bush-covered country with its many bogs, ravines and sunken roads made it extremely difficult to maintain contact with the infantry. We also had mines, shelling, mortaring and a quite tenacious enemy. C Squadron fought all day without making much headway.”

The tanks were eventually able to complete the first bound to Point 66, but the infantry, harassed by machine-guns and mortars, were forced to ground. After reorganization, the Canadian tanks and Royal West Kent Regt. captured Point 66 and consolidated, breaking German resistance and inflicting heavy casualties. Further advances were made across the divisional front with the tanks in constant action providing “magnificent support.” At 11 p.m. on May 16, 8th Indian Div. handed over its sector to 1st Canadian Inf. Div. The Gustav Line was well and truly broken.

The Hitler Line

When Alexander issued orders for the spring offensive in Italy he instructed Fifth Army to attack in the mountainous coastal sector, employing II U.S. Corps and the French Expeditionary Corps.

These forces were to advance north to the Anzio bridgehead then pursue the enemy to Civitavecchia, a port city north of Rome. The troops at Anzio were supposed to advance inland to “cut Highway 6 in the Valmontone area and thereby prevent the supply and withdrawal of the troops of the German 10th Army.”

These operations were described as “supporting” the main assault that was to be carried out by Eighth Army under Gen. Oliver Leese whose instructions were to “break through the enemy position into the Liri Valley and advance on the general axis of Highway 6 to the area east of Rome.” Alexander, who always seems to have preferred to avoid difficult issues, said nothing about what army would clear and occupy Rome. This potentially explosive issue became even more volatile when the orders Leese issued required Eighth Army “to break through the enemy’s main front in the Liri Valley and advance on Rome” leading Clark to tell his corps commander that he was to prepare plans to seize the city. Leese’s detailed orders for Operation Diadem called for co-ordinated advances by the Polish Corps against Monte Cassino, and the XIII British Corps across the Gari River. Ideally, the Germans would be forced to abandon the Cassino heights and withdraw to the Hitler Line. In this optimistic scenario, the Poles would outflank the Hitler Line from the north, assisting a breakthrough by the XIII Corps. The Canadian Corps would be held in reserve to exploit a breakthrough or to assist XIII Corps.

The terrain and determined enemy resistance prevented the Poles and the British from achieving their goals, but 8th Indian Division and 1st Canadian Armoured Brigade did succeed in establishing a shallow bridgehead across the Gari River before the exhausted, depleted infantry battalions ran out of steam. Leese decided to restore momentum by committing 78th British Infantry Div. and 1st Cdn. Inf. Div. to the struggle. Normally, these two fresh divisions–each operating with an armoured brigade and a considerable amount of artillery support–would have been part of a single corps to optimize command, control, and communication, not to mention co-ordinating intelligence on the enemy.

Since most of XIII Corps was to withdraw into reserve, the obvious solution was to place 78th British Div. under Lieutenant-General E.L.M Burns and I Canadian Corps headquarters. Unfortunately, Leese, who in common with other senior British officers had opposed the creation of I Canadian Corps was not willing to allow Burns and his staff the opportunity to direct the battle. With two corps, each deploying a division in the narrow Liri Valley, and the Poles, part of yet another corps only a few kilometres away, radio channels were soon jammed, further jeopardizing co-ordinated action.

The men of the 1st Cdn. Inf. Div. knew nothing of these problems when they crossed the Gari River on the night of May 15-16, 1944. The history of the West Nova Scotia Regiment best describes the scene the Canadian infantry encountered: “The morning sun of May 16 revealed a green paradise, one of the show places of Italy, walled in by high mountains and rolling its way north-westward in farmland thickly dotted with bushes and trees, and watered by clear mountain streams. There were orchards and fields of tall grass or young wheat, thigh deep…thickets of scrub oak on the sand flats…the streams lay in deep gullies.” The soldiers, clad in their newly issued summer denim, were at “top pitch,” anxious but ready for their part to begin.

The 1st Cdn. Inf. Bde. Group, with tanks of 25th British Tank Bde., was first into battle, taking over from Indian troops who had been stopped short of the north-south Pignataro-Cassino road.

The Royal Canadian Regt.–with tanks from the 5th Lancers–moved along the river using a tow path as the axis of advance. The French Expeditionary Corps had already cleared the south bank of the river and intelligence reports suggested an immediate German withdrawal to the Hitler Line which sliced through the area just east of the town of Pontecorvo. The RCRs soon discovered that a low hill overlooking the Pignataro road was “held in strength” and so it was decided to attack the hill with a rifle company supported by a squadron of tanks. It took some time to arrange artillery support and the attack finally went in at 5 p.m. The RCRs took the objective, capturing 60 prisoners from the 90th Panzer Grenadier Div. However, the enemy soon countered with devastating mortar and cannon fire, and the regiment was forced to withdraw to the reverse slope with its wounded.

The Hastings and Prince Edward Regt., on the right flank, bypassed Pignataro and advanced some distance before meeting serious opposition. Farley Mowat, in his history of the Hasty Ps, recalls that the Battle of the Woods, “quickly degenerated to the platoon and company level, and became a savage melee of infantry against infantry…. The Germans appeared to have unlimited supplies of shells and mortar bombs, and the regiment suffered 40 killed or seriously wounded in the first few hours.”

The divisional medical staff had anticipated such casualties and trained hard to ensure the best possible response. Each brigade was allotted a field ambulance “streamlined for battle” with Casualty Clearing Posts (CCPs) just to the rear of the forward battalions. Stretcher-bearers brought casualties from the Regimental Aid Post (RAP) to the CCP where Jeep ambulances ferried them to an Advanced Dressing Station (ADS). Here triage took place. “Group I casualties were those who showed symptoms and signs of severe shock and/or hemorrhage and included extensive burns.” These were immediately treated. Group II were those requiring emergency surgery while Group III could travel to the rear with an attached platoon of the corps Motorized Ambulance Convoy (MAC). The aim was to ensure the rapid treatment and safe recovery of more than 80 per cent of those evacuated with wounds.

Brigadier Dan Spry and his battalion commanders reported that the Germans were holding ground in front of the Hitler Line in strength. Each position would have to be dealt with in miniature set-piece attacks. Leese saw it differently. He criticized 1st Bde.’s slowness “in the face of quite light opposition.” He urged Burns to get the division moving. Burns explained the army commander’s views to Major-General Chris Vokes who ordered both 1st and 3rd brigades to mount what the official history calls, “a determined advance.” Vokes no doubt used more colourful language to Spry, who in turn ordered his reserve battalion, the 48th Highlanders, to fill the gap between the RCRs and the Hasty Ps. The 48th Highlanders were told to launch a dawn attack to seize the high ground above a stream called the Forme d’Aquino. The stream cut a diagonal gully across the valley from the town of Aquino in the north to the Liri River in the south, and there was growing evidence that the enemy was preparing to use it to slow the Canadian advance.

Kim Beattie’s superb regimental history of the 48th Highlanders, titled Dileas, provides a detailed account of the day’s action. As the battalion moved to its ‘forming up place’, the commanding officer, Lieutenant-Colonel Ian Johnston, was in a quandary. Neither his scouts nor brigade headquarters could locate the Royal Canadian Regt., which was supposed to support the attack. Meanwhile, the role of the Hasty Ps was equally obscure. Despite pressure from brigade headquarters, Johnston initially refused to launch his battalion into action until the battle plan was clarified. Spry–with Vokes on his back–was unrelenting, and Johnston agreed to organize an advance across a broad front with one of his companies hugging the bank of the Liri River which guaranteed the security of at least one flank.

No one seems to have understood that a small, dry streambed–the Spalla Bassa–was a tank obstacle for part of its length. The other great intelligence failure was ignorance about the enemy; a fresh battalion from the 90th Panzer Grenadier Regt., well-equipped with panzerschrecks, a portable anti-tank weapon. Even the heavily armoured Churchill tanks of the Royal Armd. Corps were vulnerable at close range. When they tried to join the infantry, five were quickly destroyed before the squadron withdrew.

The lead platoons of Dog Company, on the river flank, continued their fire and movement advance without tank support and managed to reach the point where the Forme d’Aquino crossed the road to Pontecorvo. Here they “were astonished to come upon a company of the Hasty Ps, hidden in the tall, green grain and among clumps of brush, and fervently glad to see the 48th Highlanders.”

Attempts to contact battalion headquarters failed in the general radio clutter so the two Highlander platoon leaders, lieutenants Norm Ballard and Doug Snively, decided to rush the enemy position on the far bank of the Forme d’Aquino. “A wild hand-to-hand melee then took place. Ballard leaped recklessly forward and killed the crew of four in the machine-gun post with grenades and snap revolver shots. Without pausing, he then hurled himself toward a sector of infantry protecting the artillery piece…. He was now out of grenades and his revolver was empty. Snatching his batman’s rifle, he leaped for the dug-in emplacement where a German officer was brandishing his Luger. Ballard jumped for the officer, kicked him in the face, forcing the lieutenant’s surrender with this bare hands.”

Snively’s 17 platoon was equally effective. They carried out a classic “right flanking” move, capturing an enemy anti-tank gun position. The capture of the vital stone bridge across the Forme d’Aquino through the initiative of two young officers and their willing men was a remarkable achievement. Ballard was subsequently awarded an immediate Distinguished Service Order, although his comrades believed his actions were worthy of a Victoria Cross.

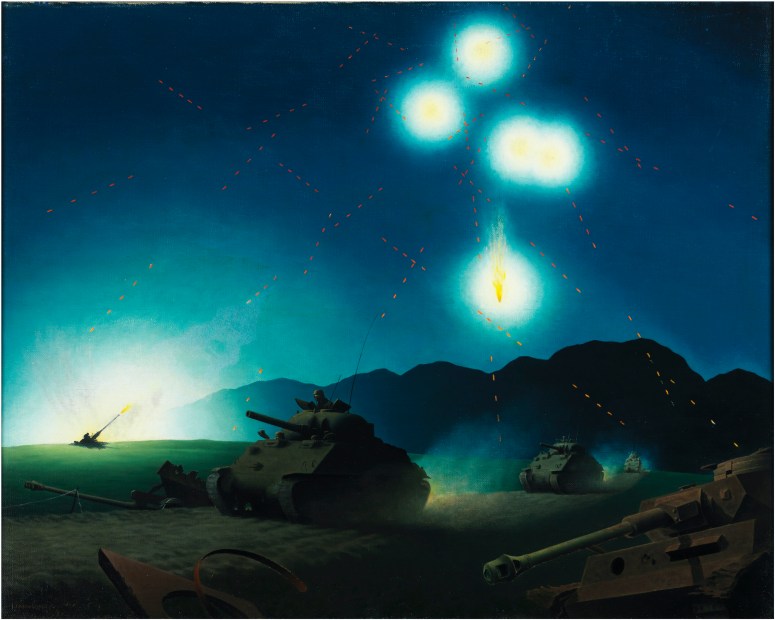

This brilliant action by two Highlander platoons was in sharp contrast to the “tedious and dangerous” struggle to try and clear the enemy from the area to the right of the road. By nightfall, Baker and Charlie companies were dug-in well short of the Forme d’Aquino and they could do little to assist Dog Company’s defence of the bridge against a fierce counter-attack. A platoon of panzer grenadiers, following behind three self-propelled assault guns, came directly towards the bridge where the battalion anti-tank gunners had posted their six-pounders. A mortar launched phosphorous flare “attached to a tiny asbestos parachute” illuminated the scene and allowed Sergeant Bob Shaw to score a direct hit on the second self-propelled gun which burst into flames, trapping the lead vehicle which was then destroyed.

While 1st Bde. fought its way forward, Brig. J.P.E. Bernatchez’s 3rd Bde. joined the advance on a one-battalion front. Bernatchez’s regiment, the Royal 22nd, led off, working with a squadron of Canadian tanks. The Three Rivers Regt. had been borrowed by Vokes when the British armoured regiment–allotted to 3rd Bde.–was delayed. The two Quebec regiments meshed smoothly and the squadron leader reported that “although the going was very bad, the infantry-cum-tank co-operation was perfect.” Radio communication and hand signals kept everyone in contact and “as each objective was cleared, a definite planned attack was underway for the next.” The infantry “never lagged behind the tanks” and by early afternoon the first objective, Point 73, was cleared and consolidated.

The West Nova Scotia Regt., along with a second squadron of tanks, passed through the Royal 22nd Regt., maintaining the momentum of the advance. When the tanks were temporarily brought to a halt by a gully, the infantry just kept going. The Germans were under orders to slow the Canadian advance to the Hitler Line and so they fought a series of delaying actions. By early evening, the Carleton and York Regt. was ready to take over and it quickly reached the Forme d’Aquino where it relieved pressure on 1st Bde.’s open flank by crossing the deep gully and establishing a start line for the next day’s advance.

A striking feature of the day was the contrast between the confused and confusing operation carried out by 1st Bde., where command and control broke down early and was never regained, and the co-ordinated movements of 3rd Bde.’s battalions. Fortunately, on May 18, Spry managed to re-established control and both brigades completed their advance to the Hitler Line in good order. It was, however, evident that the enemy had bought sufficient time to occupy these defences in strength.

When the 78th Div., with Canadian armour under its command, attempted to break through south of the town of Aquino, they met “heavy opposition in the way of mortaring and machine-gunning from well-defended and wired positions….” And so a well-organized, set-piece attack on a wide front would be necessary to crack the Hitler Line.

When Lieutenant-General E.L.M. “Tommy” Burns had taken command of 1st Canadian Corps in March 1944 he was briefed on plans for the forthcoming offensive in Italy’s Liri Valley by the commander of Eighth Army, General Oliver Leese. Two options were considered. If British XIII Corps broke the Gustav and Hitler Lines, the Canadians would pass through using Highway 6, the main road to Rome. If XIII Corps was stopped short, Burns would be responsible for the Hitler Line and the subsequent breakout across the Melfa River to Ceprano and Frosinone. Major-General Chris Vokes’ 1st Infantry Division would attack the Hitler Line with Maj.-Gen. Bert Hoffmeister’s 5th Armoured Div. taking over the advance towards Frosinone.

Planning for both eventualities began in April and when XIII Corps’ advance stalled Burns and his staff were ready to support a set-piece attack against the Hitler line. The Canadian Corps headquarters and 5th Armd. Div. had been imposed upon 8th Army, but by April, Leese was impressed. “The Canadians under Burns,” he wrote, “are developing into a very fine corps. He is an excellent commander and will, I feel sure, do well in battle.”

Burns had won the temporary support of the army commander but his relationship with Vokes and Hoffmeister was less clear. Vokes and Hoffmeister had been in action since the landings in Sicily and they were hesitant and even hostile towards newcomers who had yet to prove their competence in action. This difficult relationship may have influenced Vokes’ decision to try and bounce the Hitler Line on May 21-22 instead of waiting until the full set-piece attack, Operation Chesterfield, began May 23.

The story of the advance on Pontecorvo by the 48th Highlanders and the Princess Louise Dragoon Guards (PLDG) is scarcely mentioned in the Canadian official history, but this heroic and costly action deserves more recognition. Brigadier Dan Spry’s 1st Brigade had reached the edge of the “saucer-shaped valley” in front of Pontecorvo on May 21 as troops of Gen. Alphonse Juin’s French Expeditionary Corps (FEC) occupied the west bank of the Liri River opposite the town. Spry crossed the river to liaise with the FEC and decide if an assault over the river behind the town could turn the Hitler Line. Spry reported that the riverbank was too steep and well defended for an assault crossing of the river so Vokes, who had learned that the PLDG had captured numerous prisoners in an advance towards Pontecorvo, decided to commit 1st Bde. to a follow-up attack.

Lieutenant-Colonel Ian Johnston first heard of the plan to attack Pontecorvo at a late-night orders group on May 21. The 48th Highlanders were to lead off at first light with the Royal Canadian Regiment and Hastings and Prince Edward Regt. following to widen the breach. Tanks, including British Churchills, were available to provide support. With less than four hours available to brief his officers and complete battle preparations, Johnston protested that “such an attack without proper preparation, was inviting heavy casualties with no chance of success.” He informed Vokes that he would not take responsibility for this ill-conceived venture and asked to be relieved of his command.

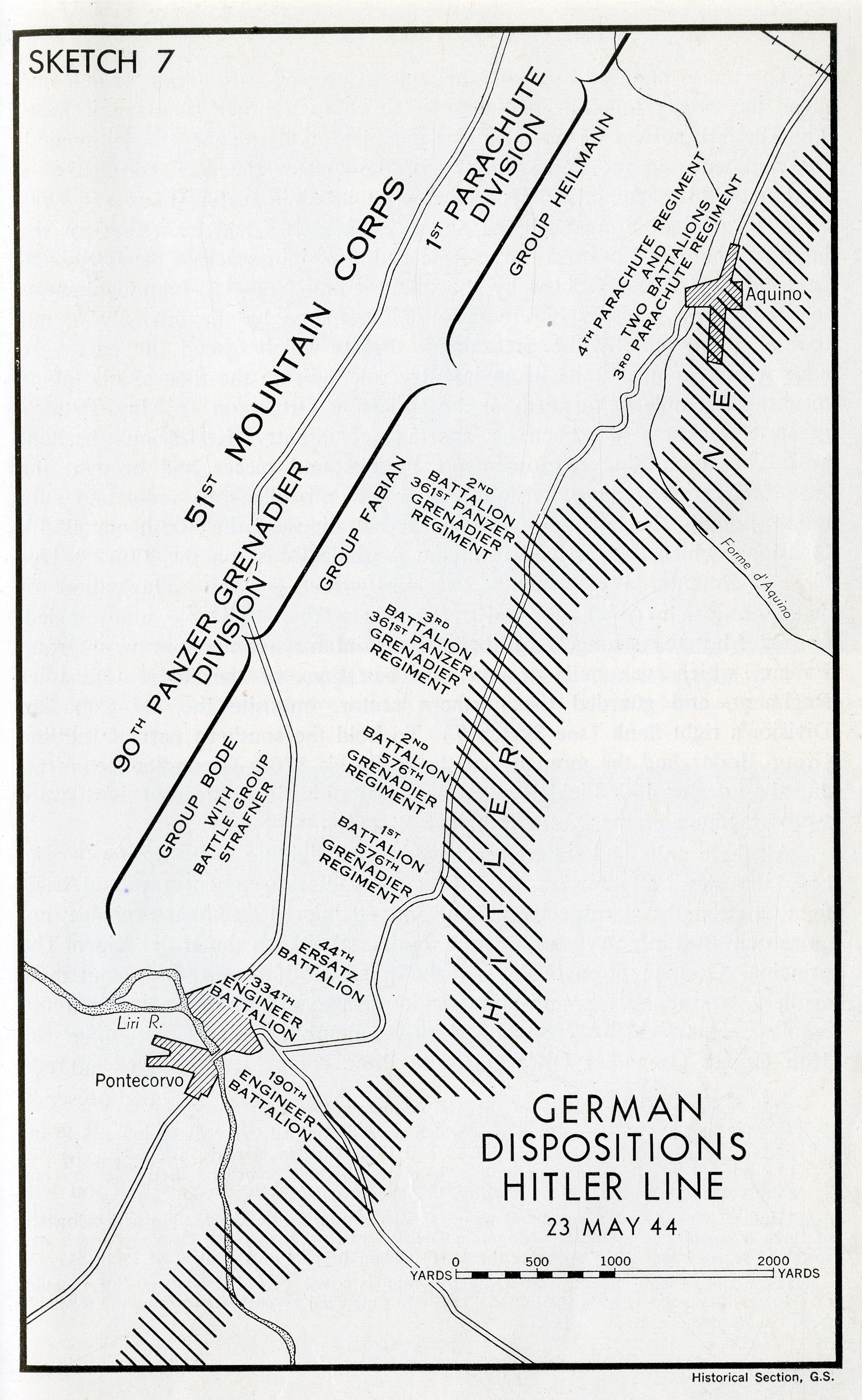

This was an extraordinary step for a battalion commander to take, and after pressure to act to support “other important operations,” including the breakout from the Anzio bridgehead scheduled for May 23, Johnston finally agreed on the condition that the attack was postponed until 8 a.m. or later if his battalion and the supporting armour were not ready. The remaining hours of darkness were used for reconnaissance and desperate attempts to obtain artillery support. The final plan called for the 48th Highlanders to breach the line and then seize Hill 106 outside Pontecorvo. Their advance began at 10:30 a.m. The defences confronting the Highlanders were part of an 800-metre-wide belt stretching eight kilometres from the Liri River to the edge of the mountains beyond Aquino. The Todt organization, using drafts of Italian labourers, had built a series of positions protected by an anti-tank ditch, barbed wire and minefields. In addition to standard field works, the Hitler Line included eight positions manned by specially trained troops employing the 75-mm gun of a Panther tank turret bricked into the ground. Each post was supported by a medium machine-gun, rocket projector and a well-camouflaged troop of self-propelled guns (SPs).

The Germans in their forced withdrawal to the Hitler Line had failed to burn the field crops so the waist-high wheat provided enough cover for the infantry to reach the wire. A troop of Churchill tanks joined the attack and as the enemy concentrated on this new threat the Highlanders infiltrated the defensive belt capturing a number of steel-domed machine-gun posts. The Germans defending the Hitler Line were short of infantry, but not firepower and the Pontecorvo zone included anti-tank positions that inflicted a terrible toll on the British armour. The Highlanders were forced to dig in and endure endless mortar and Nebelwerfer fire. Pontecorvo did not appear to be a soft spot and

Spry was told to wait until Operation Chesterfield began before committing the RCRs and Hasty Ps to Pontecorvo.

When Vokes ordered 1st Bde. to attack Pontecorvo, he kept 2nd Bde. in reserve to exploit success and roll up the German front from the south. This meant there was little time to deploy 2nd Bde. to the Aquino sector and no time to allow company commanders to recce the ground they would have to fight over. The brigade began to move to its forming up place on the evening before Chesterfield began. Tanks of 25th Bde., Royal Armd. Corps, followed during the hours of darkness.

The attack began at 6 a.m with a deafening artillery barrage on a frontage of 2,300 yards. All of Eighth Army’s artillery was available: 682 field and medium guns with an additional 76 mediums and heavies for counter-battery tasks. Yet more guns were assigned to counter-mortar shoots, and air observation squadrons were available to locate enemy guns and troop movement.

The barrage was timed to lift 100 yards after five minutes and then in further 100-yard lifts in three minutes. Smoke was fired to try and neutralize the open northern flank at Aquino. Second Bde. attacked two battalions up. As first reports suggested, the enemy was stunned by the barrage and easily overcome, but minefields, obstacles and anti-tank guns prevented the tanks of the North Irish Horse from continuing forward.

With no further progress being made, the barrage was halted at 7:50 a.m.

On the ground, the Patricias and the Seaforth Highlanders of Canada were suffering the worst carnage of the Italian Campaign. The PPCLI, on the right, was exposed to the heaviest fire. An account of its battle—written shortly after the 23rd—notes “intense mortar artillery and light machine-gun fire… taking a heavy toll of both forward and reserve elements.” The Seaforths on the left were under similar pressure and the artillery support had to be limited due to uncertainty about locations. “Casualties were now coming back in considerable numbers. Immobilized tanks continued to fire their guns until they were set ablaze by enemy fire.”

The commanding officers of the Loyal Eddies and PPCLI, lieutenant-colonels Rowan Coleman and Cameron Ware, had agreed the Loyal Eddies would follow the PPCLI forward to help consolidate the dangerous Aquino flank. At 8 a.m.—as the move began—German snipers and by-passed machine-gun posts became active and inflicted casualties, including battalion radio operators and Coleman.

On the brigade’s flank the Seaforths had advanced to the edge of the Aquino-Pontecorvo road, but the armour was held up or destroyed. Lt.-Col. Thomson reported that his men had “no anti-tank weapons except their PIAT guns.”

The Corps Commander Royal Artillery (CCRA) Brig. E.C. Plow, who was co-ordinating fire support, spent a frustrating morning issuing orders to postpone pre-arranged plans for phase two as there were no signs the infantry was able to continue the advance. His “eyes,” the air observation pilots, could see little of the battlefield which was covered in smoke and dust. At 12:27 p.m. Plow’s counterpart at 1st Div., Brig. N.S. Ziegler, asked if a “William” target, all available Eighth Army artillery, could be fired on Aquino “to try and loosen things up” as no definite targets could be located. It took just 33 minutes for batteries scattered across the Liri Valley and beyond to report ready and then receive a “time on target” signal. In the next few seconds 668 guns fired 3,509 shells weighing 92 tons at Aquino.

The artillery helped limit the volume of fire from Aquino, but was not enough to change the facts on the ground. The PPCLI’s history describes the situation: “Hour after hour the pounding continued…all three battalions could only cling desperately to the few acres they had won, waiting for aid to reach them. It did not arrive…. Liaison officers and runners go forward and do not return. There is nothing to see, walking wounded bring back black tidings but only in vague terms—map locations, enemy dispositions, everything definite has escaped them. Everyone knows the attack has failed; no one is prepared to accept the failure as final.”

May 23rd was the worst day of the war for 2nd Bde. and the costliest single day for any Canadian brigade during the Italian Campaign. Casualties totalled 543 men, 162 killed, 306 wounded and 75 taken prisoner. Many of the wounded returned to their unit after a short interval, but for the moment the brigade was spent.

In the broader picture the battle and the role of 2nd Bde. was not a “failure.” The 3rd Bde., attacking one battalion up to the left of the Seaforths, was shielded from flank fire and ignored by the enemy’s self-propelled guns counter-attacking from Aquino airfield. The Carleton and York Regt. overcame “the relentless pounding of the hostile mortars, Nebelwerfers and artillery keeping up with the barrage.” Their supporting armour, Churchills of the 51st Royal Tank Regt., “suffered heavy losses” but the “battlefield showed glaringly the price the Hun had paid and destroyed 75 mms, much vaunted 88s SPs and MK IV tanks added conspicuously to the picture of death and destruction stretching across the plain.”

The Carleton and York Regt. was able to bring its anti-tank guns forward, organize anti-sniper patrols and widen the breach before the West Nova Scotia Regt. passed through at 5:30 p.m. The WNSR had risen early—“breakfast at 0430 hour in the dark, companies moving down to the forming up place in the early morning light fitted in their proper places with amazing precision.”

Waiting under fire for most of the day put everyone’s nerves on edge and so the order to move came as a great relief. The WNSR quickly “married up” with a squadron of Three Rivers Regt. tanks which were rushed forward to replace the exhausted British tankers. “All our tank liaison training went by the board,” an infantry official recalled, “as they rolled into position through the WRECKS of the Churchills we just waved them on, got up and started forward.” The enemy had not recovered from the second phase barrage and the infantry moved steadily forward despite “rain really pouring down” and intense shelling.

Divisional and brigade headquarters could scarcely believe their ears when the lead WNSR company signalled “Caporetto,” the code word for final objective, less than three quarters of an hour after crossing the start line. The other three companies were just minutes behind as were several troops of Three Rivers tanks. Vokes had retained the Royal 22nd Regt. with two squadrons of 12 Canadian Armd. Regt. as divisional reserve. He released them to Brig. Paul Bernatchez who ordered them forward to exploit the growing breach 3rd Bde. had created in the Hitler Line. The Quebec regiments moved through the gap and turned north seizing a “tongue of higher ground” in front of the area the Seaforths had fought to secure. The breakthrough had cost the brigade 45 men killed and 120 wounded. There was also good news from 1st Bde. The 48th Highlanders had renewed its attempt to reach Pontecorvo. The Hasty Ps, ordered to join in, could not employ artillery support since no one knew exactly where the 48th Highlanders were. Spry decided to launch the Hasty P attack to the north of Point 106, hoping the enemy would be fully occupied with the 48th on the other side of the hill.

Farley Mowat’s history of the Hasty Ps, The Regiment, describes the afternoon attack as “the most brilliant single action fought by the Regiment in the entire course of the war.” Those who recall the climb to Assoro will be surprised by this assertion, but the Hasty Ps achieved a “clean breakthrough” penetrating the Hitler Line and clearing a route for the tanks at “a total cost of eight men killed and twenty-two wounded.” That night the RCRs entered Pontecorvo to find the enemy in full retreat.

Hitler’s Tenth Army had been defeated and was threatened with encirclement. The 51st Mountain Corps opposite the Canadians reported that after “fluctuating fighting, during which not only our own troops but also those of the enemy suffered severe casualties, it proved impossible to prevent enemy advances….”

Artillery fire and close combat had “wiped out” the left wing of 90th Panzer Grenadier Div. and the battalions from 1 Parachute Div. sent in as reinforcements. Since Tenth Army headquarters failed to respond to requests for assistance or instructions, the corps decided to abandon the surviving Hitler Line positions and retreat “before an orderly withdrawal became impossible.”

Tenth Army’s failure to respond was an indicator of the scale of the catastrophe overtaking the Germans in Italy. The American advance from the Anzio beachhead threatened Tenth Army’s lines of communication while the collapse of the Hitler Line meant the last field defences south of Rome had been breached. Since the available reserves had been committed the only option was a fighting withdrawal to Rome or beyond. During the night of May 23, the 5th Canadian Armd. Div. began the pursuit.

Bridgehead On The Melfa

Military historians often distinguish between the strategic, operational and tactical levels of war though they frequently disagree on their exact meanings. The term grand strategy is usually reserved for decisions made by Allied leaders like Winston Churchill and Franklin Delano Roosevelt. The grand strategy behind the World War II Italian Campaign in the spring of 1944 was to continue an offensive as a means of diverting enemy resources away from the D-Day beaches and Normandy.

To further this plan General Alexander, the overall Allied commander in Italy, ordered a broad advance towards Rome that would engage the enemy. This was to be followed by a breakout from the Anzio beachhead that was intended to trap the German Tenth Army by cutting its escape routes.

Generals Oliver Leese, Eighth British Army, and Mark Clark, U.S. Fifth Army, developed more detailed operational plans to carry out Alexander’s directive. This involved allocating roles and resources to the corps commanders who would direct the battle at the tactical level. However, the situation was complicated by the personalities and personal ambitions of both Clark and Leese. The American commander had no intention of following Alexander’s orders if it meant denying his Fifth Army the glory of liberating Rome. Leese, equally anxious to win laurels for Eighth Army and emerge from the shadow of his predecessor, Bernard Montgomery, was no less determined to achieve a rapid advance to Rome.

When 1st Canadian Division broke through the Hitler Line on May 23 the task was difficult enough without the complication of an open right flank at Aquino where elements of the elite 1st Parachute Div., supported by artillery firing from the slopes of Mount Cairo, directed intense fire on the Canadians. Aquino and Highway 6, the main road to Rome, were in Gen. S.C. Kirkman’s XIII British Corps section, but Leese wanted to keep the 78th Div. available to support an advance by 6th British Armoured Div. once the German retreat had begun. The heavy casualties suffered by 2nd Canadian Infantry Brigade on May 23 were largely the result of Leese’s decision to order 78th Div. to stage a diversionary attack on Aquino instead of a full-blooded assault.

Matters were made worse by the plan to allow XIII Corps to use roads in the Canadian sector once a breakthrough had been achieved. As the British official history notes, “this plan for exploitation contained the seeds of trouble.” General E.L.M. Burns knew about these problems. However, there was little he could do on the evening of May 23, a date all Canadians ought to remember with pride. That was when 1st Canadian Div. reported that it had forced a gap in the Hitler Line. What followed was an opportunity to send 5th Canadian Armd. Div. forward to exploit the situation.

If you visit the Liri Valley and explore the area south of Aquino where the breakthrough and breakout occurred, the challenges confronting both Canadian divisions will be readily apparent. The town straddles a creek bed—the Forme d’Aquino—a kilometre south of Highway 6 and three kilometres from the seemingly vertical mass of Mount Cairo. The hole in the Hitler Line that 1st Div. punched through was a kilometre south of the town, and it was within visual as well as artillery range. In 1944, the narrow roads leading to the Melfa River—the initial objective for 5th Armd. Div.—were simply donkey tracks that passed through enclosed fields containing olive groves and vineyards, and located on frequent and deceptive terraces crossed by razor-backed ridges. Cross-country movement was further hampered by gullies and irrigation ditches. Since Highway 6 was reserved to XIII Corps Canadian staff officers were confronted with an almost impossible situation.

The best published accounts of the battle for the Melfa are found in Doug Delaney’s biography of General Bert Hoffmeister, The Soldier’s General.

Delaney notes that Hoffmeister was at 1st Div. headquarters when Gen. Chris Vokes turned to him and said, “Bert, this is the best we can do. There is not much of a hole, good luck.” Hoffmeister ordered 5th Armd. Bde., Lord Strathcona’s Horse (Royal Canadians), 8th Princess Louise’s (New Brunswick) Hussars, the British Columbia Dragoons and the Westminster Regiment with the Irish Regt. from 11th Inf. Bde. to secure a crossing of the Melfa six kilometres away.

Hoffmeister, who had no previous experience with armour, left the detailed planning to Brigadier Des Smith who was convinced that the normal artillery barrage would be useless in this action as the dust and smoke would limit visibility and provide enemy gunners with a target line behind the barrage. Major J.W. Eaton, the brigade major, described Smith’s attempt to introduce an element of clarity into a very opaque situation: “The brigadier studied the map…and decided where—if he were in the enemy’s position—he would place anti-tank guns. These positions he marked along with any features likely to be used as enemy OPs (observation posts) and other possible gun emplacements. These localities, for example, would include the southeasterly fringe of woods facing the direction in which we were coming and points commanding any open ground our tanks must cross. Thus 105 different spots were selected and each of them ringed and numbered.”

Copies of the map were issued to all units allowing fire or smoke to be called down when needed. An air OP squadron was also available to assist the gunners.

Smith divided his brigade into Vokes Force, named for the commanding officer of the British Columbia Dragoons, and Griffin Force, named after the commander of the Strathconas. Vokes Force led off and despite rain, enemy shelling and limited artillery observation, the BCD tanks and Irish Regt. infantry worked smoothly together and secured their objective at 3 p.m. Along the way they met and destroyed the first Panther tank encountered by Eighth Army in Italy. The BCD after-action report notes: “This was the first time the regiment had seen action. The men had never been under shell fire, nor had they seen battle casualties. They responded well, and there was a general feeling of ‘let’s get at them’.”

Griffin Force passed through and by late afternoon the Strathcona recce squadron, commanded by Lieut. E.S. Perkins, reached the Melfa at a point one kilometre north of a well-marked and well-defended ford of the river. This was no accident, Smith and Griffin had selected the route to achieve surprise, now it was up to Perkins and his men to take advantage of the situation. In his account of the battle, Perkins explained that his squadron “consisted of eleven light American General Stuart or Honey tanks. From these the turrets have been removed and…a .50-calibre machine-gun is mounted.” He noted that the vehicle also carried a crew of five and its firepower, besides the .50, includes a pair of Browning machine-guns, a Bren gun, a PIAT and four Tommy guns. “We also carry prepared charges and grenades.… For the Melfa crossing, six of my tanks were for use by engineers.”

Smith’s decision to send 18 sappers (Royal Canadian Engineers) forward with each armoured regiments’ recce squadron proved to be inspired. They “cleared mines, cut diversions, filled in craters and built bridges—sometimes working without relief for stretches of 36 and 48 hours.”

The sappers with Perkins’ force helped forge a river crossing despite the steep banks. Field engineering included “altering the north bank” with three prepared charges and building a retaining wall. Combat engineers, who often served as integral parts of infantry and armoured units, rarely got the attention they deserved. However, Smith made a point of recognizing their enormous contribution.

Once across the river, Perkins and his men rushed a house and captured eight surprised paratroopers. The paratroopers were described as “big, well-built men” who were “armed to the teeth” but taken by surprise while facing south towards the obvious crossing point. As Perkins organized an all-around defence, A Squadron of the Strathconas arrived on the east bank where it came under fire from enemy self-propelled guns. There was no way the heavier Sherman tanks could cross the river. Therefore, a lot depended on the arrival of the lead Westminster rifle company. However, that unit’s cumbersome, wheeled scout cars ran into trouble when they were forced to leave the road and enter the ditches. It did not reach the crossing until 5 p.m., two hours after Perkins’ first encounter with the enemy.

Major J.K. “John” Mahony then took command, extending the bridgehead and inspiring everyone with his determination. A major counter-attack led by four German tanks was met by concentrated small arms fire and PIAT bombs that fell short of their target. Despite this limited threat the enemy tanks and infantry turned away. They succeeded in overrunning an isolated Westminster platoon, but lost a tank crew to a couple of grenades thrown by Private John Culling. Just before midnight a second Westminster company crossed the river bringing the anti-tank platoon with its six-pounders. The bridgehead was still very small and under heavy shell fire, but it was secure. For their valour and inspiring leadership, Mahony earned the Victoria Cross and Perkins the Distinguished Service Order.

Smith brought the Irish Regt. forward with orders to attack at first light on the 25th. Traffic jams slowed the movement of artillery and anti-tank units, delaying the advance to midday. It was late evening before they reached the river. After getting what sleep they could the battalion deployed, under fire, to attack on a wide front to the south of the Westminster bridgehead.

The Westminsters, “who had a keen personal interest” in the success of the Irish attack, decided to help by destroying an enemy machine-gun post so that when the Irish began its attack the few Germans remaining at the river quickly surrendered. Both battalions, now supported by a squadron of BCDs, moved forward to the lateral road a kilometre beyond the Melfa. The BCD squadron had to deal with long-range, anti-tank fire from 88-mm guns. It lost seven tanks, but it stuck with the infantry and provided the essential covering fire. As the infantry dug in, using a one-pound explosive charge carried with their K-rations, the Germans drenched the area with fire “for seven long hours.” This delayed any further advance and allowed them time to assemble their scattered forces at Ceprano.

Meanwhile, 1st Div. had joined the advance to the Melfa. Early on May 24, the commander of the Princess Louise Dragoon Guards, Lieutenant-Colonel Fred Adams, led a battle group that consisted of his own regiment, two squadrons of Royal Canadian Dragoons, one squadron of Three Rivers tanks and the Carleton and York Regt.

The RCD “Report on Ops…” recalled that “no one will ever know exactly what happened during the advance or in what sequence.… Time and again the lead cars were ‘left in the blue’…yet all the while, in spite of the confusion, the advance went on.” The RCDs reached the Melfa, close to its junction with the Liri where the far bank is steep and high. On May 25, the Carletons found a crossing and quickly established a bridgehead. Joined by a troop of Three Rivers’ tanks, the Carletons pronounced their position “snug.” But while the Germans were thin on the ground they still had enough mortar, nebelwerfer and artillery fire in range to prevent a further advance. The engineers waited until dark to bridge the river.

Field Marshal Albert Kesselring and his army commanders were now faced with several unpleasant options, all of them potentially disastrous. The American breakout from Anzio was making good progress and seemed to be directed at Valmontone, a town astride Highway 6. This was the German supply and escape route for their Tenth Army. If Valmontone fell only narrow mountain roads would be available to link the Tenth and Fourteenth Army fronts. Kesselring decided to send his best reserve unit, the Hermann Göring Panzer Div., to check the American advance. He ordered Germany’s LI Mountain Corps, situated opposite the Canadians, “to occupy a new line of defence on the northwestern bank of the River Melfa.” No reinforcements were available, but as usual the line was to be held with no withdrawal unless authorized by Kesselring or Hitler. The swift Canadian advance had made these orders meaningless. “The situation,” LI Mountain Corps reported, “is the result of the sustained artillery bombardment preceding the advance of massed tanks which are followed by the infantry. However brave the troops may be, they are powerless against tanks.” One wonders what Perkins with his six Honey tanks or the Three Rivers troop commander with his four Shermans would make of this explanation for the loss of the Melfa Line.

Kesselring responded to the crisis by issuing a directive that called for the paralysis of the enemy’s offensive spirit “by the infliction of heavy casualties… done by fanatical defence of the designated main defence lines,” including the Melfa. Despite this order the war diary of LI Mountain Corps notes the decision to withdraw as “the enemy increased the depth of his penetrations over a wide front and the complete collapse of the section could only be prevented by the decision of the corps to withdraw.”

Much of Tenth Army was already retreating north, including the artillery. The Germans at the sharp end were now faced with unopposed artillery, air attacks and armour. No less than seven German battalions had been “completely destroyed” since May 23. The fate of Tenth Army now rested in the hands of General Lucian Trustcott’s XI U.S. Corps which was to head for Valmontone with the aim of closing the main escape route.

On the morning of 25 May a battle group from 1st Canadian Division crossed the Melfa securing 5th Division’s left flank. To the right, 78th Division under XIII British Corps was unable to clear the town of Aquino or the nearby airport, used as a base for German armour.

As a consequence, the Governor General’s Horse Guards (GGHG), the divisional recce regiment tasked with protecting the flank up to the corps boundary, was left on its own and “fought almost continuously throughout the day” before reaching Highway 6, situated beyond Aquino. The New Brunswick Hussars were also drawn into skirmishes south of Aquino. With the right flank temporarily secure and the Irish Regiment across the Melfa, the second phase of the operation—the advance to Ceprano—could begin. The 11th Bde. battle group, comprised of the Irish Regt., the Cape Breton Highlanders and the armour of the New Brunswick Hussars, was delayed by traffic congestion on the division centre line. The Hussars spent the night several miles from the river, waiting to be “topped up” with fuel.

The next morning, Brigadier Eric Snow, who had taken command of 11th Bde. after “the Arielli show”, discovered that the guns of 17th Field Regt. as well as the Hussars were still on the move. He postponed the attack until 4:30 p.m. The advance was met by heavy enemy fire, but by last light the infantry was consolidating on the brigade objective. While Snow was issuing orders for the next day, the division’s precarious supply line was under threat from a new direction—British Eighth Army.

Leese had decided that 6th British Armd. Div. should take over the British advance along Highway 6 and so he ordered Gen. Sidney Kirkman, the commander of XIII Corps, to make it happen. Kirkman, armed with this authority, went to Canadian Corps headquarters and told Burns that 6th British Armd. Div. required access to the bridge Canadian engineers were building across the Melfa. Historian Doug Delaney has questioned this decision to “cram two armoured divisions into a corridor only fit for one” and called it “inexplicable,” but Leese’s motivation is clear enough. The American advance out of the Anzio bridgehead was well underway and so risks had to be taken if a British division of Eighth Army was to play a part in the liberation of Rome. This was a political, not a military decision, and as Leese later admitted, the result was “great congestion and serious delay.”

Canadian Corps headquarters first heard of this a “terrible decision” on the afternoon of May 24. When the Canadians were preparing to send 11th Infantry Bde. forward to Ceprano. Corps and divisional officers were then faced with a series of co-ordination problems that would have challenged the most experienced staff. Clearing the Canadians off their divisional centre line could not be completed on May 24, and the next day the 6th Armd. Div. ran into an unmarked minefield which further postponed the advance. Leese and Kirkman blamed the Canadians for these delays. Ironically, the tanks of the Calgary Regt. entered Aquino on the 25th during the last stages of the German withdrawal. If Leese had waited 24 hours, 6th Armd. Div. could have stayed on the main highway.

Traffic congestion continued to cause problems on May 26, preventing two detachments of engineers from reaching 11th Bde. With just one route available, the advance slowed. In his Report on the Battle of the Liri Valley, Brigadier Snow wrote:

“The going was very bad. The country was extremely close and can be likened in places to bush country in Africa…shelling and mortaring were very heavy during the whole time. The (General Officer Commanding) GOC (Hoffmeister) was with me and he was continually urging that we get on, that the advance was much too slow and that something must be done.”

The situation got worse as the day progressed and casualties mounted. Snow decided Ceprano could not be reached during daylight and since both his flanks were open he ordered his battalions to dig in. Hoffmeister, who was under pressure from corps, countermanded the order and the advance continued. Patrols reached Ceprano and found it empty. The next morning, May 27th, the Perth Regt.—“spurred on by the tenacity and energy” of their commanding officer, Lt.-Col. J.S. Lind, crossed the river to find the enemy holding the high ground, Point 119, just beyond Ceprano.

Two attempts to rush the position failed, and when Snow postponed further action to the next day Hoffmeister was furious, insisting that “there was no excuse for not capturing it.” Snow in turn was unhappy with the Cape Breton Highlanders who in his view were “slow” and “sticky.” No one asked the combat troops who might have mentioned something about the Germans and their ability to concentrate their resources to repel the only troops actually across the Liri.

Hoffmeister decided to commit his armoured brigade group despite the “razor-backed ridges” that ran at right angles to the line of advance. The divisional engineers had selected a bridge site that required a complex “double-double” Bailey bridge to cross a “120-foot gap with near vertical 20-foot riverbanks.” However, before construction began, Adams Force from 1st Inf. Div. reached the river at a point where a single Bailey bridge could be quickly positioned. Hoffmeister decided to send his armour forward by this route and informed corps headquarters that his sappers were tired and the bridge was no longer needed. The Chief Engineer, Eighth Army, intervened and demanded that the bridge be built so that 78th British Div. could use it. The Royal Canadian Engineers official history notes that “all went well during the night, with morning came trouble. Perhaps fatigue, over-eagerness to make good time and inexperience contributed to a degree of carelessness. As the bridge was pushed across the gap, the launching nose hit the far bank and buckled.” The repairs were not complete until late on the 28th. By then the Germans had withdrawn to new defensive positions.

The Canadian advance to Frosinone resumed the next day, but progress across the complex terrain was slow. Both Burns and Hoffmeister were unhappy with 11th Bde. and decided to place a brigade group from 1st Div. under Hoffmeister’s command before turning over the advance to Maj. Gen. Chris Vokes’ more experienced division. The change could not be made immediately and both of Hoffmeister’s brigades were ordered to capture the villages of Pozi and Arnava before handing over.

Leese had withdrawn 6th British Armd. Div. from the pursuit, but Highway 6—the only good route north—was reserved to 78th Div. This left the Canadians with a narrow corridor through close country, crossed by stream beds, tributaries of the Sacco River.

Brig. Des Smith decided that no more than one armoured regiment could get forward and so he sent two companies of the Westminsters with the British Columbia Dragoons. The battle group was forced to swing south using a 1st. Div. bridge as the Ceprano crossing was reserved to 78th Div. On May 29, they set out for the high ground overlooking Pozi, but were slowed by mines and blown bridges. Italian civilians helped guide the tanks around minefields and by evening the men were on their objective. The two lead BCD squadrons had lost five tanks to enemy action with more than a dozen “bogged down, stuck on banks, tree stumps, etc.” This BCD after-action report stressed the smooth co-operation between the infantry, armour and self-propelled anti-tank battery, but noted that the “type of country during the advance to Pozi objectives was entirely unsuitable to tank action…this task should have been carried out by an infantry brigade.”

The 11th Bde. had paralleled the BCD/Westminster advance with instructions to seize Pofi and three objectives on the high ground near Arnara, code named Tom, Dick and Harry. The Perths took Pofi “well after dark” by “scaling the very steep sides of the town in the face of shell fire and snipers. At first light, a Perth Regt. company entered Arnara without meeting further opposition and was “warmly welcomed by inhabitants.” The Irish Regt., tasked with the capture of Tom—the ridge southeast of Arnara—won the position “in hand-to-hand fighting.” More than 30 Germans were captured and several killed.

The most dramatic incident of the day involved the Lord Strathcona’s Horse which ran into a battle group of Panther tanks and self-propelled guns of 26 Panzer Div., serving as a rearguard for the German retreat along Highway 6. Three Strathcona tanks were hit immediately, but the one remaining Sherman in the lead troop, commanded by Corporal J.B. Matthews, “manoeuvred his tank backwards and forwards so as not to present a stationary target, and destroyed a Panther, a 75-mm gun and a Mark IV tank.” The next morning, May 31, 1st Div. took over the advance.

By then Fifth Army had abandoned the attempt to cut off the German retreat and turned north to gain thew glory of liberating Rome. Furious at the exclusion of Eighth Army, Oliver Leese, unable to publicly criticize Clark, lashed out at the Canadian Corps. The slow advance of his army was, Leese insisted, not due to his own faulty command decisions but to the inexperience of Lieut-General Burns and his staff. He met with Lieut-General Ken Stuart, the Canadian Army’s Chief of Staff, demanding the replacement of Burns who he claimed was “not up to the standards of corps commanders in Eighth Army.” Burns he argued should be replaced preferably by a British officer, Major-General Charles Keatly who commanded 78th Division. Stuart listed politely to these comments, but replied “the replacement of Burns by a British officer would be a mistake and could only be considered as a last resort.” He informed Leese that he would make an investigation before taking any action.

Apart from the 1st Canadian Armd. Brigade, which was still in action under British command, the Canadians were out of the line in a training and rest area when Stuart arrived. His conversation with Burns was friendly, but frank. Stuart stated that he planned to interview Burns’ divisional commander and principal staff officers. “My future action,” he told Burns, “would largely depend on what I will be able to find out.” Stuart recognized that discussing a senior officer’s competence to command with his subordinates was “unusual” but so was the situation. Stuart met with Vokes and Hoffmeister separately and then interviewed Brigadier Des Smith and J. E. Lister, the senior logistics officer.

All four officers agreed that “mistakes had been made” and each “accepted a portion of the blame.” Stuart’s report continues: Both divisional commanders “were quite outspoken about the corps commander. They respected his tremendous fairness in all his dealings…and found no fault whatever in any tactical decision he had made” during the Liri operation.