While the men of 1st Canadian Infantry Brigade were fighting for the high ground overlooking the Sicilian town of Adrano, Winston Churchill, Britain’s prime minister, was aboard the Queen Mary en route to “Quadrant,” the first Allied conference to be held at Quebec City. This was Churchill’s second trip across the Atlantic in 1943 and as with his visit to Washington three months before, the purpose was to seek agreement on future strategy. During Trident, the May 1943 conference, Churchill had persuaded American President Franklin Delano Roosevelt to agree to begin planning operations designed to exploit the capture of Sicily by invading the Italian mainland.

The Americans had insisted on limited action against Italy because they were concerned that Churchill and the Chief of the Imperial General Staff, Field Marshal Sir Alan Brooke, were trying to expand the Allied commitment in the Mediterranean. General Marshall, Roosevelt’s indispensable military adviser, was determined that operations in Italy would not be allowed to interfere with the buildup for Overlord, the invasion of France. He persuaded the British to accept May 1, 1944, as D-Day for Overlord with 29 American, British and Canadian divisions, including seven from the Mediterranean, positioned in England by early 1944. Churchill won agreement to attack the Italian mainland, designed to “knock Italy out of the war” and engage as many German divisions as possible, but he had to accept that Italy would soon become a secondary theatre.

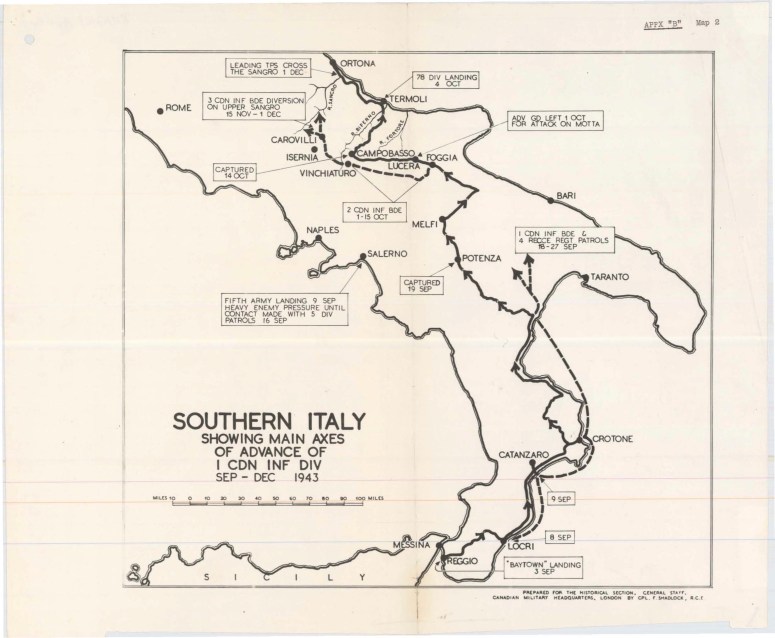

The first Quebec conference confirmed these arrangements, including “Baytown,” an attack across the Straits of Messina from Sicily to the toe of Italy and “Avalanche,” an assault landing at Salerno south of Naples. The Canadian government played no part in these discussions. Prime Minister Mackenzie King was present for photo ops with Churchill and Roosevelt, but he “accepted the position that the higher direction of the war was exercised by the British prime minister and the president of the United States.” The Canadians did learn that their troops in Sicily were scheduled to participate in Baytown and Lieutenant-General Kenneth Stuart, the chief of the general staff, gave his formal approval on Aug. 17.

The soldiers of 1st Canadian Division and 1st Canadian Tank Bde. began preparing for their part in Baytown on the basis of lessons learned in the Sicilian Campaign. The key to success in battle was skill in the use of ground for the attack, defence and the defeat of the enemy’s immediate counter-attacks. Training focused on “fieldcraft, siting of weapons, camouflage, cover, observations, use of compass, and map-reading.” Infantry battalions were to organize and train sniper and scout platoons while emphasizing the role of the three-inch mortar and Bren gun carriers in supplying firepower. Each brigade was urged to deploy the Saskatoon Light Infantry platoons of 4.2-inch mortars and medium machine-guns well forward. The terrain in Italy made heavy mortars, with a 3,000-yard range, crucial weapons in “softening up or smoking an objective” and accuracy required “a high standard of drill and discipline.” The Vickers machine-gun, “one of the best weapons in our armoury,” was most effective when used in enfilade with a section of two guns as the fire unit. Training in infantry-tank co-operation was also stressed and all were reminded of the need for the strictest anti-malarial precautions.

Everyone agreed that the terrain dictated the methods used in planning an attack. Once the fire plan was in place, rifle companies needed to advance while dispersed on a wide front. They were also to avoid the tops of ridges. The best approach was to stick to defilade and shadow and if in doubt to take the long way around. Above all, the idea was to keep moving once the attack started. Stopping would be a sure way to bring enemy mortar fire down on you.

While the soldiers trained, Major-General Guy Simonds and his staff officers developed detailed plans for the division’s part in Baytown, a curiously limited operation to be carried out by Eighth Army. Simonds outlined the division’s task at an Aug. 24 conference. The Canadians together with 5th British Div. were to capture a beachhead on the mainland side of the Straits of Messina “so that the straits are free for the use of our own shipping.” The secondary purpose was to “draw enemy resources against the beachhead” to assist the success of the Anglo-American landings at Salerno that were to take place after the beachhead at Reggio di Calabria had been secured.

Simonds was probably aware that Montgomery was unhappy with the minor role assigned to his army. Monty was not used to being a supporting actor and once it became clear that Mark Clark, the American general in charge of Operation Avalanche, would fight the main battle, Montgomery “sulked in his caravan” and allowed Baytown to develop as a set-piece assault landing with an elaborate and unnecessary bombardment of an undefended coast. Few resources were allotted to the pursuit of the enemy who were known to be planning to withdraw from the southern tip of Italy.

Simonds decided to plan for a pursuit role as well as the bridgehead battle. He selected 3rd Canadian Inf. Bde. for the assault landings with 2nd and 1st brigades to follow. He warned his brigadiers that once ashore he would not hesitate to pool the limited transport available “to make one brigade mobile, stripping the assault brigade to a skeleton to do so.” Unfortunately, the loss (to enemy submarine) of a shipment of Canadian-made four-wheel-drive vehicles had not been made up and the Canadians were forced to rely upon borrowed two-wheel-drive lorries that had “seen lengthy service in Africa.” First Div. staff were grateful for the loan, but they made it clear that when new Canadian trucks arrived they would return the British trucks promptly.

Third Canadian Inf. Bde. had not played a major role in Operation Husky–the invasion of Sicily–partly because it had performed poorly in pre-invasion training. Sicily provided an opportunity to fix some problems and improve the level of company training but Simonds was still unhappy with Brigadier M.H.S. Penhale, a permanent force officer, who he thought was too cautious and too old for active command. Penhale’s preparations for the mainland landing seemed well organized and the rehearsal went smoothly, but on D-Day of the actual landing there was much confusion, and fortunately little resistance. The German 29th Panzer Div. began a staged withdrawal and the Italian coastal division quickly surrendered.

Simonds ordered the Canadians to advance inland beginning on D+1. He had to follow orders to secure the mountainous core of the “toe,” the Aspromonte, instead of advancing along the coastal road. The decision to send Canadian troops into this incredibly difficult country made no military sense. The roads–often little better than tracks–climbed barren hills through a series of switchbacks. The enemy was bound to withdraw from the area or surrender once the “toe” had been bypassed. Also, the Canadian battalions committed to the mountains were in no position to respond when Alexander urged Eighth Army to advance north “regardless of administrative (logistical) consequences.” Montgomery ignored this order. He told the Canadians to move south to the coast where they were to pause and build up resources.

Major A.T. Sesia, the divisional historical officer kept a detailed diary in September 1943 and his entries capture the character and flavour of this strange interlude.

3 September. The night was pitch-black and no lights were visible from the enemy shore…. At precisely 0345 hours our artillery barrage opened up…. The noise from these guns kept the night air reverberating with a steady roar. Every now and then tracer shells would cross the water in a horizontal line of flight. Firing along fixed lines they guided the landing craft to their proper beaches…. The barrage lasted until 0530 hours. Here and there fires were burning on the enemy coast and every now and then the sky would be lighted up a greenish blue glow indicating a direct hit…. All morning the news from the fighting front was good. Practically no opposition was encountered…. We drive off the beach into Reggio di Calabria…another air attack took place and enemy fighters shot up the town and dropped bombs too close for comfort…. Thus, did I, for the first time, set foot on the land of my forefathers. Reggio was deserted…the people had fled to the hills, the population had dwindled from 170,000 to 20,000 when the invasion of the mainland appeared imminent.

4 September. As we drove through the town, I saw that the city, possessing many beautiful buildings, was so battered by our air bombing and shelling that there was hardly a building left unscathed…. Apparently all day yesterday considerable looting went on. It is probably difficult to differentiate between looting and scrounging…the generally accepted view is that looting is sheer vandalism, in scrounging one takes what one needs to render more efficient the prosecution of the war.

His diary entry for Sept. 5 notes that out patrols have reached far inland in all directions, but have not contacted any Germans. It also states that the enemy has carried out extensive demolitions to hinder the advance. “The mountains in this area form part of the Aspromonte chain and rise in height up to 6,000 feet. We are therefore pretty well confined to tracks and roads….

“6 September. Immediately upon leaving Reggio we climbed the high hills by way of steep winding roads…. After darkness had fallen we drove without lights up and down hair-raising grades and sharp bends. In a way it was a godsend that we could hardly see more than five or 10 feet ahead of us since we knew we were driving along a road with no guardrail above ravines ranging in depth from 600 to 2,000 feet. To add to the discomfort it commenced raining and soon developed into a downpour…. Apparently the Germans have withdrawn…and the Italians refuse to fight….

“7 September. We pushed off at noon…a slow trip due to demolitions and diversions. Warning signs such as “Danger! Use four-wheel drive if you want to see Canada again!” Heavy guns are firing to the northwest of us from naval craft which are supporting the landing of 231st Bde. (on the west coast of the “toe”).

The entry for Sept. 8 notes that he spent most of the morning at Operations Command. “The situation on our front is fluid…our forward troops have in no way made contact with the enemy…. Italy has surrendered. This news did not surprise me, as it was evident since the invasion of Sicily that the Italians were not prepared to continue the war. What lies in state for 1st Canadian Div. is now a matter of conjecture until such time as a new plan is worked out.

“9 September. The situation up front is still unchanged. No actual contact with the Germans has been made…. The BBC announced this morning that a large British and U.S. force has landed near Naples [Salerno]. We packed up early this morning, proceeded in convoy 57.2 miles…surrounded by awe-inspiring scenery…. At every town, village and hamlet the inhabitants stood outside their homes to cheer us.”

The entry for Sept. 10 says that ever since the armistice, Italian soldiers have been wandering along the sides of the roads unshaven, discouraged and demoralized–all heading for their homes.

11 September. Last night orders were issued for division headquarters to proceed to an area north of Catanzano…a fairly modern city built on a high feature.

12 September. Proceeded to headquarters of the 104th Mantova Div. with…Lieutenant-Colonel Geoffrey Walsh (the Royal Canadian Engineer commander) to confer with Italian (engineering commander) and lay on certain tasks for repairing roads. The road to Carlopoli was a macadamized state highway, well banked with concrete ditches along the berm…very few of our troops have passed along this route…the Germans had in fact left the area only a day ago. We had been as far ahead on our western flank as our recce troops had been on the eastern flank.

13 September. Gen. Montgomery and the Corps Commander, Gen. Sir Miles Dempsey, were at division headquarters to present to officers and men decorations and awards which they had earned in Sicily. During lunch with the D.A.A.G. (Deputy Assistant Adjutant General) Frank Wallace, I remarked that it was high time he was made a lieutenant-colonel. He replied that in the Canadian Army in England there were so many lieutenant-colonels they could form fours with them and he was not going back because he didn’t know how to form fours.

The entry for Sept. 14 reports heavy fighting is going on in the Naples area. It notes that a British armoured division landed last night near the scene of the fighting.

15 September. News from Naples very vague and from this it can be assumed all was not going well. We in 13th Corps were so far behind we could do little to relieve the pressure. However, once we reach Nova Siri our advance will continue with 5th Div. following the coast road and 1st Canadian Div. on their right flank in the mountains.

The next day Simonds ordered Lt.-Col. Pat Bogert, the commanding officer of the West Nova Scotia Regiment to take command of an all-arms battle group. Its task was to strike for Potenza, a road and rail junction 60 miles east of Salerno. The Canadians were back in the war.

Boforce

When Operation Baytown–the Anglo-Canadian invasion of mainland Italy–was in the planning stages, Major-General Guy Simonds, the general officer commanding 1st Canadian Division, informed his brigade commanders that he would employ mobile battlegroups if the enemy simply withdrew.

On D-Day plus four, X Force, under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel C.H. Neroutsos, the commanding officer of the Calgary Tanks, led the advance along the coastal highway, but on Sept. 9, 1943, Montgomery ordered the Canadians to pause and regroup as the “build up across the straits from Sicily is very slow….”

The next day, Gen. Sir Harold Alexander, who commanded both 8th British and 5th United States armies, urged Montgomery to “maintain pressure against the Germans so that they cannot remove forces from your front and concentrate them against Avalanche.” Sept. 9 was D-Day for Operation Avalanche, the landings at Salerno, and Alexander was understandably worried about the enemy reaction to the amphibious assault south of Naples.

Avalanche had been planned in the context of negotiations for an Italian surrender, with 82nd U.S. Airborne seizing Rome and Fifth Army advancing swiftly from Salerno to Naples. However, Allied intelligence analysts failed to understand Hitler’s determination to support Mussolini and hold onto as much of Italy as possible. The men of Fifth Army had cheered the news of the Italian surrender as the convoys approached the beaches, but were shocked by the speed and intensity of the German reaction to the landings. Four of the five German divisions in southern Italy were moved to Salerno to seal off and destroy the bridgehead. Alexander urged Montgomery to “maintain pressure against the Germans so that they cannot remove forces from your front and concentrate them against Avalanche.” The battle hung in the balance for the next six days without any support from Eighth Army. According to Montgomery, Eighth Army “fought and marched 300 miles in 17 days, in good delaying country against an enemy whose use of demolition caused us bridging problems of the first magnitude… Fifth Army did their trick without our help–willing as we were.”

The British official historian C.J.C. Molony suggests that Montgomery did try to implement Alexander’s orders, but “administrative difficulties rather than the enemy” prevented a rapid advance. His description of these difficulties is worth quoting at some length. “Transport is the bugbear of armies and, like original sin, is the everlasting occasion of accusation, railing, disturbed consciences, and censorious, vain preachings. In modern armies there is at once too much transport and not enough. The chief causes of this condition are elaborate weapons greedy for huge quantities of heavy ammunition, high military social standards which require for the urban man in uniform much food and medical care, and in the urban man himself a capacity to endure hardship far lower than that of the harshly nurtured man of Minden, of Sebastopol or of First Ypres. Yet it is idle to look for a Golden Age of hard-bitten sparseness in an imaginary past. In 1914, the kind eyes of 5,592 horses, the transport of an infantry division of that day, rested on a marching crocodile of men only 18,000 strong but 15 miles long, and staff officers ‘swore terribly in Flanders’. Their successors have done the same there and elsewhere for kindred reasons.”

Few independent observers believe that transport problems were responsible for Montgomery’s failure to press the advance with any sense of urgency. None was communicated to the Canadians who spent four days resting near the beaches of the Adriatic before beginning an unopposed advance along the coast towards Taranto, the scene of the famous torpedo-bomber attack upon the Italian fleet in 1940. When Taranto, located on the heel of Italy’s boot, was seized by 1st British Airborne in an unopposed action. The Canadians were ordered to turn inland and advance to Potenza, a road and rail junction 50 miles east of Salerno.

Alexander had given Montgomery a direct order on Sept. 17 to “secure Potenza” and he in turn gave the task to the Canadians. Simonds thought his instructions were too vague and wrote to Gen. Sir Miles Dempsey, the corps commander, noting he was “not quite clear as to whether it is now desirable to make ‘military noises’ in that direction as quickly as I can, or whether we should lie up until the whole division is ready to advance.”

Simonds proposed to move quickly on Potenza “unless I hear from you to the contrary.” He met with Lt.-Col. Pat Bogert, the commanding officer of the West Nova Scotia Regiment, and told him he was to command a motorized battlegroup comprised of a squadron of tanks from the Calgaries, engineers, a battery of self-propelled artillery, a platoon of medium machine-guns (Saskatoon Light Infantry), plus a troop from the divisional anti-tank and anti-aircraft regiments. A company from 9th Field Ambulance, Royal Canadian Army Medical Corps, completed what became known as “Boforce.” The advance north began on the morning of Sept. 18.

Today’s traveller can drive on a modern highway, the S407, from the sea to Potenza. In 1943, most of the route was over narrow roads that made their way up into the mountains through a series of spectacular switchbacks. Following the original route gives a much better idea of the achievements of Boforce, but today the bridges and culverts are intact and the only “enemy” is a fast driver headed in the other direction.

An account of the challenges faced by Boforce, based on the West Nova Scotia Regt. war diary, reads: “At 0500 hrs in the early morning of 19 Sep, A Company …moved forward to the blown bridge just west of Laurenzana to cover the operations of the engineers who were constructing a diversion. When these were in hand, A Company moved forward on foot followed by Lt.-Col. Bogert’s command party and D Company. The force was now moving along a steep defile at the confluence of the Fiumara d’Anzi and the Fiumara Camastra, both with dry but substantial river bottoms. Scarcely a mile ahead of the column, German sappers blew a crater in the road and another diversionary operation was necessary.

“Shortly afterwards, as A Company rounded the bend overlooking the river beds, the bridge carrying the road across their junction was blown and the enemy demolition squad opened fire on the leading troops. Fire from three-inch mortars was immediately brought down, an enemy lorry was hit and the Germans hastily withdrew. Lt.-Col. Bogert placed tanks at the head of the column as soon as they could be brought forward in order to frustrate for the future any similar activity on the part of enemy demolition parties. Just before reaching Anzi, another blown bridge was discovered and D Company went forward on foot while the remainder of the battalion closed up in troop-carrying vehicles. Anzi was entered at approximately noon and three German vehicles, which were visible on the road beyond, were engaged by the leading tanks and withdrew hurriedly. In addition to the increasing number of craters and blown bridges and culverts, the road from Anzi onward was studded with Tellermines.” A Tellermine was one of 40 different types of German anti-tank mines. Various kinds contained from 10 to 12 pounds of explosive.

Potenza, the largest city in the region of Basilicata, was founded in pre-Roman times as a village on the slope of a south-facing ridge above the Basento River. The poor agricultural land had led to the depopulation of the rural areas. However, Potenza had developed as a regional centre around its 12th- century cathedral. Beginning on Sept. 13, the Allied air forces began attacks on the city’s railroad yards and road junctions. Potenza, crowded with refugees from the Salerno battle area, was targeted by Allied heavy bombers on six consecutive days and much of the city was destroyed in these attacks with heavy loss of life.

The decision to continue to bomb Potenza is just one example of the lack of overall strategic direction of this phase of the Italian Campaign. Allied intelligence, based on Ultra and other sources, had reported German intentions “to throw the Allies back into the sea” at Salerno. However, by Sept. 14 the crisis in the beachhead was ending and Eighth Army was finally on the move north. The first signs of a German withdrawal were noted on Sept. 17, but no one ordered the Allied air forces to cease attacking a town or the railway yards that the Allies would soon need.

Historian Lee Windsor, who has studied the battle for Potenza and walked the ground, describes the initial attack by the rifle companies of the West Novas as one that “sacrificed the stealth of a footborne approach for the speed of using trucks.” Unfortunately, mines blocked this approach and sacrificed surprise. Two West Nova companies were pinned down in the dry riverbed and the advance stalled. The Germans had planned to hold Potenza with a regiment of 1st Parachute Div. but orders to withdraw to a new line left Potenza to be defended by a company-sized battlegroup ordered to stage a delaying action. When the Canadians mounted a second attack, using artillery, armour and an additional infantry battalion–the Royal 22nd Regt.–the German paratroopers withdrew. Canadian doctors treated 16 wounded Germans as well as 21 Canadians. However, the real tragedy of Potenza was the number of civilian casualties, estimated at over 2,000, including several hundred dead.

Major A.T. Sesia, the divisional historical officer reached Potenza on Sept. 21. “The city itself,” he wrote, “lies sprawled partly on the height immediately north of the river and on the northern bank of the river itself…at the immediate approaches to the town there was considerable damage. The artillery and especially the air force had created huge craters…good cars were destroyed or burnt out and some were blown great distances by the force of exploding air bombs.” While exploring the city, Sesia noted a huge group of civilians in front of a bakery where bread was being baked for the first time in 10 days.

The German Tenth Army, responsible for the eastern sector of the Italian peninsula, had ordered 1st Parachute Div. to the Foggia-Manfredonia area to block the British advance along the Adriatic coast. The German divisional commander noted that the flat Foggia Plains “were particularly ill-suited for campaigning with the weak forces of this division” so everything possible must be done to delay the Allied advance until more troops were available.

The general need not have worried. Logistical problems and a lack of urgency at Allied headquarters led Montgomery to regroup his Eighth Army along the Ofanto River just 25 miles north of Potenza. The Canadians were told to secure Mount Vulture and the town of Melfi but no further advance was anticipated until Oct. 1.

The German high command also issued orders on Sept. 22, instructing the soldiers of Tenth Army to adopt measures outlined in a directive entitled Exploitation of Italy for the Further Conduct of the War. This order demanded that “extensive use be made of the Italian male population for further military and economic purposes.” Both civilians and soldiers were to be conscripted for construction battalions and “extensive use” was to be made of conscripted drivers, mechanics and fitters “in order that the German soldiers may be freed up for fighting.” Supplementary orders required the confiscation of material in the Naples and Foggia areas that might be of value to the German war effort, especially locomotives, train cars and trucks. Material that could not be removed was destroyed.

The Canadians witnessed one of the most dramatic examples of Hitler’s scorched-earth policy when a patrol from the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry reached Atella, a village south of Melfi. That is where the Germans destroyed a section of the Apulian Aqueduct, the major source of water for the Foggia area and the heel of Italy.

As the Germans withdrew to Foggia and began construction of a series of defensive positions known collectively as the Winter Line, XIII British Corps (1st Canadian and 5th British infantry divisions) settled into a comfortable routine. The 1st Div. war diary for Sept. 29 reported “strong rumours that there is a war on” but nothing interfered with “putting on a sports meet in the middle of a campaign.” The diary entry continues with the notation “…the GOC (general officer commanding) has developed jaundice and had to be evacuated to hospital. This is a bad blow to the division as it appears we are about to enter our heaviest battles so far.”

Jaundice or infective hepatitis was one of several serious diseases to plague the soldiers who fought in the Mediterranean theatre. During the summer of 1942, two brigades of the New Zealand Div. had a very high incidence of jaundice while holding positions near El Alamein, North Africa. The ground there was heavily contaminated by enemy dead and feces. This experience prompted efforts to find ways of improving hygiene in forward areas, but hundreds of cases were reported in both Tunisia and Sicily.

Brigadier J.H. Palmer, the consulting physician at Canadian Military Headquarters, studied the incidence of hepatitis among Canadian troops in Italy. He noted that an epidemic began in Sicily and reached its peak in October 1943, re-emerging in a more virulent form in the spring of 1944 when more than 6,000 Canadian soldiers were admitted to hospital suffering from the disease. The average period of disability from infective hepatitis was 50 days and even mild cases were given several weeks to recover. Unfortunately, Simonds proved to be a poor patient. After several days of “confinement” at divisional headquarters he insisted on returning to duty. He did just that, but was forced to enter hospital when the classic yellow jaundice symptoms appeared. Brig. Chris Vokes became divisional commander in Simonds’ absence and he was to command during the first heavy fighting experience on the mainland of Italy, which we will examine in the next section.

Pushing To Campobasso

Throughout the Italian Campaign senior Allied commanders were able to obtain a running commentary on German intentions, courtesy of Ultra. By 1943, the code-breakers at Bletchley Park, the British government’s communications headquarters situated 80 kilometres northwest of London, were reading messages encrypted by the German forces on Enigma machines with minimum delays. At both Eighth and Fifth army headquarters, a small group of officers and non-commissioned officers–known as the Signals Liaison Unit–provided generals Mark Clark and Bernard Montgomery with detailed reports on enemy plans and their order of battle. The problem was that in 1943 the Germans were undecided about what strategy to pursue in Italy.

German Field Marshal Erwin Rommel argued it was essential to conserve manpower and withdraw to a line north of Rome. Hitler seemed to agree so Eisenhower and Alexander ordered an immediate advance to secure Naples and the Foggia plain. After a brief pause, Rome was to be captured by converging attacks carried out by both Allied armies. Delaying actions were to be expected, but the real fighting would, they believed, begin next spring north of Rome.

On Oct. 1, Ultra reported the gist of an interview between Field Marshal Albert Kesselring and Hitler in which Hitler ordered an active defence on the whole front giving up as little ground as possible. By Oct. 8, Ultra was able to report details of German plans to hold a winter position on the Bernhardt Line north of the Sangro River. Hitler’s intelligence sources had reported the movement of Allied troops out of the Mediterranean and he concluded that the Allies were hoping to secure Rome as a political prize without a major commitment of troops. This offered Germany the opportunity to restore a freed Mussolini to power, and hold much of Italy with a small army that would rely on good interior lines of communication. The Italian theatre of war was allotted an inflow of 18 supply trains a day from Germany and France, providing substantial reserves of ammunition, fuel and food to supplement the large quantities of stores seized when the Italian army was disbanded.

The Allied armies faced a very different situation. Montgomery repeatedly complained that Eighth Army lacked the supplies to wage an effective campaign. He warned the Chief of Imperial General Staff that both supplies and reinforcements would be needed to advance to Pescara as the “country in front of us is good defensive country and skilful demolitions would make the next advance slow.” He then asked the key questions about the Italian Campaign. “What do you want to do? I presume you want the Rome airfields, do you want Rome for political reasons, and to be able to put the King back on his throne? Do you want to establish airfields in the Po Valley? Do you want to drive the Germans from Italy? Are you prepared to have heavy losses to get any or all of the above?”

Montgomery offered his own view, suggesting it was “a mistake to drive the German forces from Italy.” The Allies required enough of Italy “to enable our air forces to be able to reach the southern German cities and the Romanian oilfields” and “keep the Germans guessing about our intentions” but he warned a great deal of fighting would be needed if the Allies were to reach northern Italy. Brooke could provide no answer because while he and Churchill favoured an aggressive campaign in Italy, the Americans took a very different view. They insisted that Operation Overlord, the invasion of France, had absolute priority.

While this debate played out, Eighth Army began its advance with Britain’s 78th Division, made up of veterans of the Tunisian and Sicilian campaigns, advancing along the Adriatic coast. The 78th, known as the Battleaxe division, was to be assisted by an assault landing behind enemy lines at Termoli, a small port north of the Biferno River. No. 3 Commando and No. 40 Royal Marine Commando, with the support of the Special Raiding Squadron, captured the town (Operation Devon) in the early hours of Oct. 3. The commandos then handed the port over to 78th Div.’s 56th Brigade which arrived by sea.

This well-executed manoeuvre should have forced a German withdrawal to the Sangro River some miles to the north but instead the enemy decided to try to recover Termoli and ordered the 16th Panzer Div. to counter-attack. The 56th Bde. had embarked without artillery or armoured support which was to arrive by land once the Biferno River was bridged. Unfortunately, heavy rains slowed this task and the lightly armed infantry found itself under attack from powerful panzer battlegroups. The commandos were recalled to help hold the perimeter but the town could not be held for long unless the river was bridged so that armour and anti-tank guns could cross. Only one British armoured regiment (County of London Yeomanry) was in action on Oct. 4.

More armour was needed immediately and the job was given to the Three Rivers Regt. which had landed at Manfredonia on Oct. 1. By the afternoon of Oct. 5, the Canadian tanks were crossing the Biferno and the next morning they joined in the battle. The Three Rivers Regt., commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel E.L. Booth, had distinguished itself in Sicily but this was to be its first tank-versus-tank engagement. The 16th Panzer Div. was equipped with MK IV Specials, tanks with additional armoured skirting and a better gun than the Shermans. Success, therefore, depended on the careful use of ground. The regiment claimed 10 enemy tanks destroyed in the two-day battle and won wide praise for its role in forcing an enemy withdrawal. Following the battle, the commander of the 38th (Irish) Bde. presented a shamrock pennant to Booth and told a British reporter that “it was the first time in the war that I have ever seen everything go exactly as it was supposed to…the tanks and infantry co-operated in complete textbook style–it was wonderful.”

The defeat of the German counterattack at Termoli forced the enemy to withdraw to the Sangro River. During their retreat, the Germans used delaying tactics designed to buy time for the construction of better defences. Enemy units received a directive outlining the use of “lines of resistance.” Such positions were to be arranged by setting up strongpoints manned by small groups who could withdraw at night if heavily engaged. No two lines were to be less than 10 to 12 kilometres apart so that Allied artillery could not fire at the second position without moving forward. These were the tactics encountered by the men of 1st Canadian Div. when their move from Foggia to Campobasso began. General Guy Simonds, who was evacuated to hospital with infectious hepatitis (jaundice), had outlined plans for the advance before handing over to Brig. Chris Vokes. A strong vanguard force organized around the divisional recce regiment, the Princess Louise Dragoon Guards, with a squadron of Calgary tanks and a company of the Royal Canadian Regiment, led the way from the start line at Lucera. They ran into the first enemy “line of resistance” at the village of Motta Montecorvino which the official history describes as sitting “like a thimble on a pointed hill atop the first main ridge.”

Lt.-Col. F.D. Adams, who commanded the vanguard, decided to wait for the follow-up force led by the Calgary commanding officer Lt.-Col. C.H. Neroutsos. The rest of the Calgary tanks and RCR companies arrived but most of the guns of the artillery field regiments were stuck in traffic south of Lucera. Neroutsos decided to go ahead without proper fire support but the German paratroops were able to drench the approaches with machine-gun fire, separating the Canadian tanks and infantry.

Neroutsos and Lt.-Col. Dan Spry, the RCR commander, decided to withdraw the tanks and plan a staged night attack once enough artillery had arrived. A short intense barrage fired at the town was upstaged by a thunderstorm with sheets of lightning that outdid the gun flashes. The RCR companies discovered that apart from a few rearguards the enemy had melted away towards their next “line of resistance.”

While the battle for Motta raged, a squadron of Princess Louise Dragoon Guards, probing the hill tracks west of the main highway, encountered one of the most peculiar units in the Allied order of battle, Popski’s Private Army. Major Vladimir Peniakoff, a Belgian-born, British-educated son of Russian refugees, had been working in Cairo at the outbreak of war. After initial adventures behind enemy lines with the Long Range Desert Group, Popski–as he was universally known–commanded No. 1 Long Range Demolition Sqdn., attacking German supply dumps.

After El Alamein and Tunisia, the jeep-borne force, now with official PPA shoulder flashes, was sent to Italy where it landed at Taranto in September 1943. The PPA was on the road deep behind enemy lines within days, shooting up German convoys as they withdrew from Potenza and Bari. On Sept. 30, Popski and his men, working their way north on the corps’ boundary, were more than happy to join in an impromptu attack on a German platoon positioned to provide flank protection to the strongpoint at Motta. The combined force attacked the position from the rear and none of the enemy got away to fight another day.

The 1st Canadian Inf. Bde. continued north towards Campobasso with Highway 17 as their centreline. The 48th Highlanders were tasked with the next bound to Volturava. As the regiment’s historian notes, “the apparent tough-nut of Volturava was easily cracked” because the enemy had selected better defensive positions on the San Marco ridge north of the town. Fortunately, an independent battlegroup made up of the 48th’s Charlie Company, a troop of Calgary Shermans, anti-tank guns, armoured cars plus the invaluable heavy mortars and machine-guns from the Saskatoon Light Infantry, had worked their way along a parallel route to the east of Highway 17.

The battlegroup commander, Major Ian Wallace realized that the German paratroopers holding the high ground overlooking the main road had neglected to occupy the even higher ground behind their position. Wallace got his lead platoon onto this feature and ordered it to hold their fire until they could be reinforced. Several short, sharp artillery shoots forced the paratroopers back into their slit trenches until Brig. Howard Graham could arrange a co-ordinated attack with the RCR joining the 48th Highlanders. The preliminary barrage fell short and the RCR companies were late so the formidable San Marco feature was attacked by just two Highlander rifle companies.

The Wallace battlegroup staged a risky raid on the enemy employing a single platoon and the troop of tanks. When the lead tank was crippled by a mine, Lieutenant Blair Eby and his men “flung themselves among the scattered German slits…with Tommy guns and brens stuttering from every hip.” The paratroopers panicked and abandoned their forward slope positions. When the RCR attacked the village of San Marco that night, a well-directed artillery barrage ended further German resistance. By morning the paratroopers were gone.

It was now 3rd Bde.’s turn to take the lead against a new enemy formation, the 29th Panzer-Grenadier Div. A first attempt to cross the Fortore River failed. It took place near the broken spans of the Ponte dei 13 Archi. However, a cross-country advance by the West Nova Scotia Regt. and Carleton and York Regt. forced the enemy to abandon Gambatesa, a town four miles beyond the river. The Germans disengaged, surrendering a series of hills and villages in an attempt to conserve manpower and hold a new blocking position on Highway 17 at Jelsi. Both the Germans and Canadians were suffering a steady stream of casualties but the Canadians continued to press forward using hill tracks as well as the highway. The Royal 22nd Regt. and the West Novas overcame the Jelsi position at considerable cost which forced the enemy back towards Campobasso.

To the south, 2nd Bde. had advanced across the grain of the country in a series of moves that tried the patience and endurance of everyone. Still outfitted in their light Sicilian campaign clothing, the troops were soon frequently “dog tired and wet” and often without food. Nevertheless, “skill and persistence” paid off and the enemy, who had developed a high opinion of the Canadians and a justified fear of their artillery, decided to abandon Campobasso. Artillery also proved to be crucial in 2nd Bde.’s battle for Vinchiaturo. When Brig. Bert Hoffmeister’s battalions were in position the enemy decided to withdraw “to prevent heavy losses…from superior forces and artillery fire.”

Unfortunately, the next line of resistance south of the Biferno River proved unexpectedly difficult to break. Villages like Orantino, San Stefano and Mongagano and peaks such as Mount Vairiano had to be captured before Campobasso, slated to become an administrative and rest centre, could be safe from shelling. So, a series of sharp, exhausting attacks were necessary.

By Oct. 21, this task was complete but Montgomery’s decision to employ 5th British Div. in an advance to Isernia as a way of diverting attention from a major offensive along the Adriatic coast required the Canadians to seize and secure a start line beyond the Biferno. Simonds, who left hospital early to resume command of the division, told his weary men that they were to “hit a good hard blow” at the enemy before the British attack began. The first phase, capturing the village of Colle d’Anchise and the high ground known as Point 681, was assigned to the Loyal Edmonton Regt. with support from the troopers of the Ontario Regt. fighting their first battle on the Italian mainland.

The tanks had to wait for the engineers before crossing the river and the Edmonton Regt. was forced to give up part of the village when their PIAT anti-tank weapons proved ineffective against German tanks. Once the Canadian armour arrived the panzer battlegroups withdrew. The next day 5th British Div. launched its diversionary attack reaching Isernia on Nov. 7. By then the Canadians were enjoying a well-earned respite in Campobasso.