Sicily

One of the most enduring myths about Canadian military history is that historians and the general public have concentrated their attention on the campaign in Northwest Europe ignoring the “D-Day Dodgers” and the battles in the Mediterranean. This view persists despite the popularity of Farley Mowat’s books, the high quality of the official history of the campaign and the excellence of other studies. The Canadian role in Italy is also the subject of some of our best memoirs including Sydney Frost’s Once a Patricia and Strome Galloway’s books and articles. We also have the superbly designed and illustrated Canadians and the Italian Campaign 1943-45 by Bill McAndrew. A title in the series sponsored by the Directorate of History and Heritage of the Department of National Defence. Once again no expense has been spared in producing the volume, but do not let the coffee-table format confuse you. McAndrew has written an original and insightful account which will please veterans, the general reader and professional historians. Throughout the book McAndrew uses personal accounts to illuminate and humanize the analysis of a complex story.

The decision to attack the island of Sicily was made at the Casablanca Conference in January 1943. General George C. Marshall, the U.S. Army chief of staff, and most of his countrymen, opposed the plan but were unable to offer a viable alternative. When Marshall was forced to accept the first phase of Winston Churchill’s strategy of “closing the ring”, he had warned President Franklin Roosevelt that the landings in North Africa in November 1942 would postpone the invasion of France until 1944, drawing the Americans into Britain’s Mediterranean strategy. At Casablanca he accepted the logic of employing the Anglo-American armies against Sicily, a million men could not be kept out of action for a year, but Marshall still regarded the Mediterranean as a diversion which prolonged the war.

Historians are naturally attracted to issues involving large personalities and great debates so there are numerous studies of the Allied leaders and their interaction but surprisingly little attention has been paid to purely military considerations. By the summer of 1942, when the key decisions about the future were made, Churchill and his chiefs of staff had lost confidence in the leadership, training and morale of the British Army. The long series of defeats from Dunkirk to North Africa and the Far East seemed to raise fundamental questions about the fighting qualities of the British and Commonwealth soldier. The victory at El Alamein in the Egyptian desert had soothed some of the anxiety but British operations in Tunisia moved slowly. When the Americans suffered a tactical defeat in Tunisia at Kasserine Pass, the British concluded that the American forces were badly trained and poorly led. Could such men overcome the experienced and superbly equipped divisions of the German Army on the fields of Northwest Europe? The answer for most senior British commanders was a resounding no. Far better to continue operations against Italy until Bomber Command and the Soviet armies had weakened Germany. By 1944 the Allies would have much more battle experience and knowledge of waging war within a coalition. The Soviet victory at Stalingrad seemed to promise that there would be time enough to learn.

The story of the transformation of the Commonwealth armies is usually seen as beginning in the desert under the leadership of General Bernard Montgomery. It is in fact far more complicated than that for much of the change took place in the United Kingdom. The quality of weapons and weapon systems may not determine the outcome of battles but if one side is consistently inferior the odds of defeat are very great.

When the politicians in Ottawa decided to press the British to include Canadian units in the next major operation in the Mediterranean they knew little of the actual state of their troops in Britain. The Canadians, like their British counterparts in England, had spent most of the war preparing to defend the island from invasion. This had begun to change in the summer of 1942 but as the historian John A. English has shown the army was far from ready for operations against a well trained enemy.

There is nothing sinister in the failure of the British and Canadian high command to train and equip a modern army, it was a matter of priorities. Before 1943 virtually everyone agreed with Churchill’s view that “only the navy can lose the war and only the air force can win it.” The army was for home defence and sideshows like North Africa. By the end of 1942 such a view was no longer sensible and was abandoned.

Consider for example the changes made in the equipment of the Canadians after they were selected for action in Sicily. Our armored units, the Calgary Tanks, the Three Rivers Regiment and the Ontario Regiment were equipped with the reliable, and by 1943 standards, powerful Sherman tank. The infantry battalions were introduced to the new Projector, Infantry, Anti-Tank, or PIAT, the British bazooka. The PIAT had a dangerously limited range and could not be relied upon to fire accurately but it did provide the foot soldier with a useful anti-tank weapon which an infantry section could take into battle.

Assignment to Sicily also meant that the battalion anti-tank platoons finally got their hands on the six-pounder anti-tank gun, still a scarce commodity two years after its introduction. The gunners of the divisional anti-tank regiment were equally pleased with the 17-pounder self-propelled gun which was quite accurately described as equal to the famous German 88-mm. The Saskatoon Light Infantry, the division’s support battalion, was introduced to the 3-inch mortar. By 1943 smokeless powder and improved range made the weapon a match for the German 81-mm mortar.

Other innovations helped to build confidence and improve effectiveness. The question now was whether the Canadians could find the leadership and commitment to succeed in battle. Lieutenant-General Andrew McNaughton, the commander of the First Canadian Army, first chose Harry Salmon, a decorated WW I veteran with a reputation as one of the best trainers of soldiers in any army, as divisional commander. After Salmon’s death in a plane crash, McNaughton jumped a generation selecting Guy Simonds to replace him.

Simonds was to become the best known Canadian general since Arthur Currie, but in 1943 the 40-year-old Simonds was an unknown quantity. To command a division without ever having fought in a battle is unusual at any time but to begin a career with an assault landing is extraordinary. Simonds was nevertheless the obvious choice because he was simply the outstanding professional soldier in the army. He had excelled in all previous appointments and was well regarded by the British who were prone to be suspicious of Canadian officers.

Simonds inherited a divisional staff and five brigadiers who were a good cross section of Canada’s officer corps. Major-General Chris Vokes who led the 2nd Brigade, and who followed Simonds in command of the division, is the best known, but the group included Bruce Matthews, an outstanding artillery officer and future divisional commander, as well as many others who proved to be capable leaders. With their militia backgrounds Matthews and Brigadier Howard Graham were the exceptions among 1st Division’s mostly permanent force senior officers.

The Canadians had just over two months to prepare for the invasion of Sicily and they used their time well. The most serious setback in the first phase came when three merchant ships in the Slow Assault Convoy were sunk with losses of 58 men, 500 tanks and 40 guns. Divisional headquarters and the field regiments were severely hampered by equipment losses and a good deal of improvisation was needed. The landings themselves were accomplished with few casualties and the division’s first inland objective, the airfield at Pachino, was secured when the Royal Canadian Regt. overwhelmed the defenders of an artillery battery.

Contemporary historians are critical of nearly every aspect of Operation Husky. Carlo D’Este, the leading American student of the campaign, titled his book Bitter Victory, emphasizing the escape of German forces to the mainland as well as the caution and confusion of Allied leadership. D’Este believes that the attritional battles fought by the Eighth Army in Sicily were both poorly managed and unnecessary. Normally this kind of history is annoying but D’Este cares deeply about the plight of the ordinary soldier caught up in the horror of war and imposes harsh standards on all decision makers.

The Canadian experience in Sicily produced a very different collective memory. Sicily was the army’s first campaign and most thought it was a great success. When Montgomery ordered the Canadians to push hard in a left hook to outflank the German defences at Catania the division moved quickly to fulfil its tasks. The story of the next 30 days cannot be repeated too often. The extraordinary achievement of the Hastings and Prince Edward Regt., the Hasty Ps, in climbing a mountainside at Assoro was first told by the unit historian Farley Mowat who wrote:

Each man who made that climb performed his own private miracle. From ledge to ledge the dark figures made their way, hauling each other up, passing along their weapons and ammunition from hand to hand. A signaller made that climb with a heavy wireless set strapped to his back–a thing that in daylight was seen to be impossible. Yet no man slipped, no man dropped so much as a clip of ammunition. It was just as well, for any sound by one would have been fateful to all.

Bill McAndrew, normally a stern critic of the British-Canadian way of war, sees Assoro as just one of the extraordinary Canadian achievements in Sicily. The battle for Leonforte fought by the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry and the Loyal Edmonton Regt., was less spectacular. However, the “speed and audacity” of the battle-group commanded by Captain Rowan Coleman which raced to the relief of the Loyal Eddies was a promising example of a combined arms operation which the division would have to master if it was to succeed in battle.

The next major battle, to seize the village of Agira, involved a more methodical and less successful set-piece attack employing five field and two medium artillery regiments. McAndrew suggests that this conventional artillery-based plan was a poor substitute for the mobile fire and movement operations which proceeded it but German resistance was stiffening all across the front as the enemy began to evacuate non-combatant troops to the mainland.

The fall of Agira came just as the Italian Dictator Benito Mussolini was deposed. His successor, Marshal Pietro Badoglio, maintained that Italy would continue to fight but few, and least of all Hitler, believed him. The invasion of Sicily had accomplished one of its major purposes.

Where were the vaunted Allied air forces and the powerful Royal Navy while the Germans ferried men and vehicles across the narrow waters to the toe of Italy? The Royal Air Force, with the Royal Canadian Air Force’s No. 331 (Medium Bomber) Wing under command, flew just 591 sorties over the straits during the evacuation. Such bombing, from high altitudes at night, against precision targets, produced predictably minor results. If the full weight of the North African Strategic Air Force had been diverted more might have been accomplished but no one had the authority to require this. The tactical air force did attempt to interfere but the heavy concentration of anti-aircraft guns and the lack of urgency at the highest levels of command meant that operations were on a modest scale. The same lack of direction and fear of shore-based gun positions kept the navy well clear of the crossing points.

The Sicilian campaign made a significant contribution to the Allied war effort. The landings in Sicily were an important factor in Hitler’s decision to end offensive operations in Russia. The reinforcements the Germans sent to Italy, especially the Luftwaffe squadrons, demonstrated Hitler’s sensitivity to developments on his southern front. If the Allies maintained pressure Hitler would have no choice except to transfer German divisions from France and Russia to Italy and the Balkans. If Husky was an operational failure it was a strategic victory of great value.

Beginning The Battle For Sicily

The decision to invade Sicily was made at the Casablanca Conference of January 1943 over the protests of American military leaders, who feared that once committed to Sicily, Allied forces would be tied down indefinitely in the Mediterranean. The British countered with the argument that knocking Italy out of the war could be accomplished without fighting a costly attritional battle on the mainland. Operation Husky was the first step to reaching that goal. The Americans agreed to Sicily, leaving the decision about mainland Europe to a later date.

Allied planners had disagreed about almost every aspect of Husky, including estimates of the strength of the enemy. Italian divisions had fought well in Tunisia and the Italian Sixth Army defending Sicily, deployed nine infantry divisions supported by twenty tank and self-propelled gun battalions. It was thought that the Italians, together with two German mechanized divisions, could only be overcome through massive force and everyone focused on preparations for a complex combined air, naval and army operation.

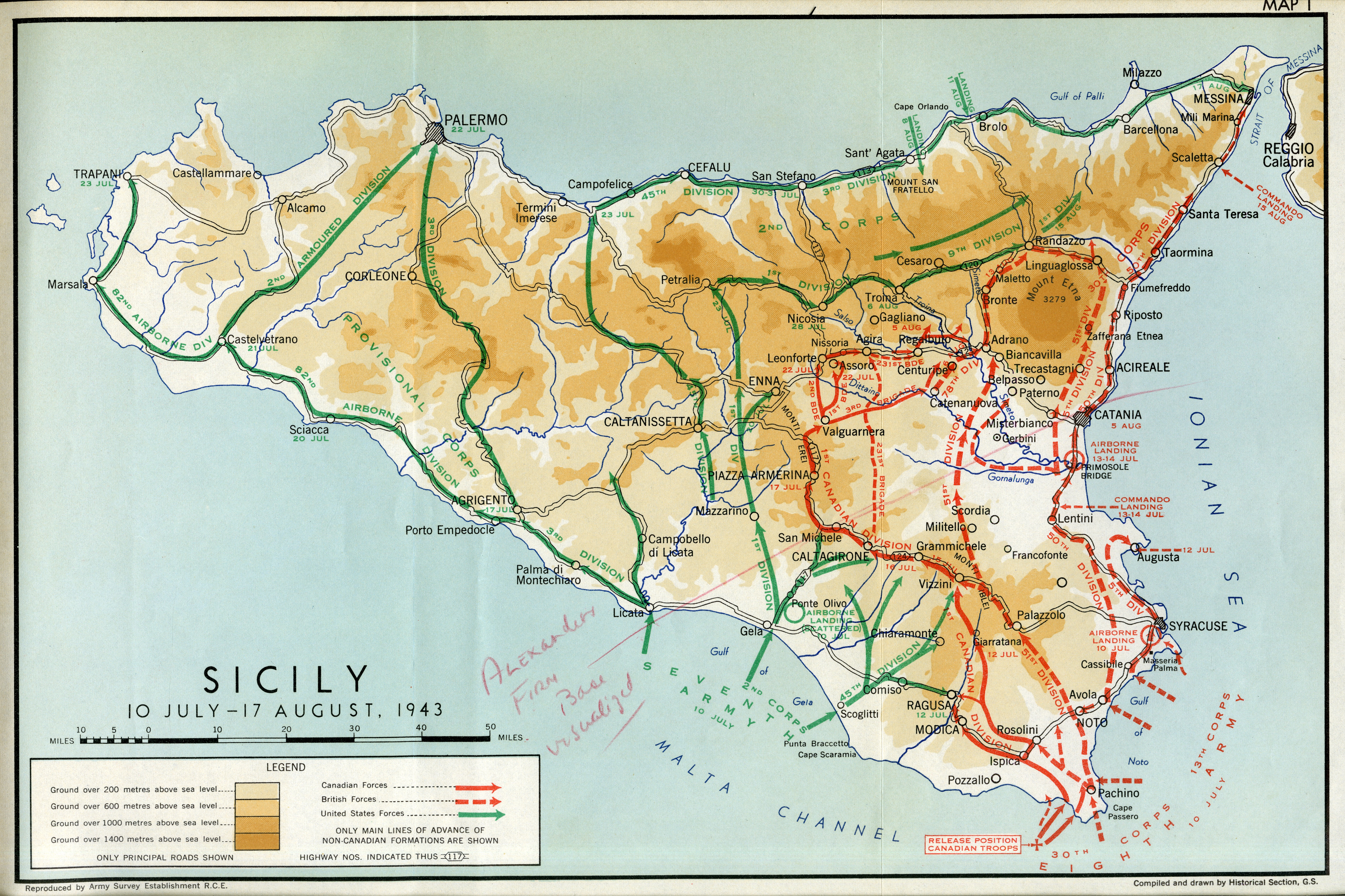

Initially, the planners called for two widely separated landing areas, one for each of the Allied armies. Montgomery, the commander of the British Eighth Army, insisted on the principle of concentration and convinced the Supreme Commander, General Dwight D. Eisenhower, to accept a plan to land both the American and British forces in south- eastern Sicily. Montgomery’s veteran divisions would then engage the enemy on the Catania plain before advancing north to Messina and securing the island. General George Patton’s Seventh U.S. Army would protect the British flank. The idea of employing large airborne forces to support the landings and secure vital bridges was also approved, despite doubts about the training of the aircrew slated to carry the paratroopers to battle.

Unfortunately, Montgomery’s overall concept of operations proved to be deeply flawed. Much of the Italian Sixth Army was weak, immobile and demoralized (Click Here for a Map of German Dispositions). Most Italian soldiers and generals had come to hate the Germans and were ready to welcome the Allies. The Big Red One, the U.S. 1st Inf. Div., dealt with the only serious opposition encountered in the landings, but the Germans were able to block the main British advance. A frustrated Montgomery persuaded the Army Group Commander, General Harold Alexander, to allow Eighth Army to cut across the American line of advance taking over roads assigned to the U.S. 45th Div. This decision was made in the full knowledge that 1st Cdn. Div., which was to take over from the Americans, had lost much of its transport to German U-boats and needed time to pause and reorganize before continuing towards Enna. A furious George Patton was forced to withdraw 45th Div. and move it to the west, but refused to accept the passive role Montgomery and Alexander had allotted to his army and began his own campaign to liberate Sicily, turning west to Palermo before advancing to Messina along the north coast.

Major-General Guy Simonds knew nothing of the background to his new orders when he was told to take over the advance to Enna and seize the vital road network in the centre of the island. The 1st Inf. Bde. (The Royal Canadian Regiment, the Hastings and Prince Edward Regiment and the 48th Highlanders) led the advance, using most of the available transport. The Hasty Ps, with a squadron of Three Rivers Regt. tanks, were in the lead when the town of Grammichele was reached. The town sits on a ridge overlooking the surrounding countryside, an ideal defensive position that was adopted by a battlegroup of tanks and anti-tank guns of the Herman Goring Div. This was the division’s first serious encounter with the Germans and the Hasty Ps dealt with the enemy in textbook fashion. With one company deployed as “fire company” two companies with a battery of self-propelled anti-tank guns began a right flanking attack while the Three Rivers tank squadron engaged the enemy armour. The German battlegroup was forced to withdraw, abandoning equipment and stores. The Canadians suffered 25 casualties in this brief encounter.

The 48th Highlanders took over the lead, reaching the outskirts of Caltagirone early the next day. Caltagirone, a city perched on a long narrow ridge, had been identified as the headquarters of the Goring Div. and was targeted by Allied bombers. With fires still burning and the winding streets blocked with rubble, it was fortunate that the enemy chose to withdraw to new defensive positions rather than force a house-to-house battle.

The German high command initially classed the Allied invasion as a Dieppe-level raid that would be quickly crushed, but by July 15, Hitler decided that western Sicily must be abandoned and a new defensive line based on Mount Etna established. The German commander was informed it was important to fight a delaying action. However, no risks were to be taken with the German divisions in Sicily especially “the valuable human material” that was to be saved for the defence of the mainland.

The 2nd Cdn. Inf. Bde., made up of the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry, the Seaforth Highlanders of Canada and the Loyal Edmonton Regt., under orders to advance “vigorously” towards Enna, reached Piazza Armerina in time to receive a rough reception from a battalion of the 15th Panzer Grenadier Div. The Edmonton regiment bore the brunt of the fighting, suffering 27 casualties before the enemy “melted away.” The modern visitor to Piazza Armerina will find a city of charming medieval alleys, steps and lanes leading to the Piazza Garibaldi in the city centre. The Edmonton’s recall a bitter struggle for the approaches to Piazza Armerina in a country where “everything went uphill” and movement was over cobbled roads or dirt tracks in scorching heat.

The 3rd Cdn. Inf. Bde., which included the Royal 22nd Regt., the West Nova Scotia Regt. and the Carleton and York Regt., took their turn leading the advance towards the narrow gap in the mountain south of Valguarnera. The enemy had established a strong blocking position there and the Van Doos encountered heavy, well-directed fire. Brigadier M.H.S. Penhale ordered the Carletons to attack the position from the east, forcing a German withdrawal. The West Novas carried out a wide, cross-country flanking movement to reach the Enna road behind the Germans.

The divisional commander, under growing pressure to move more quickly, had ordered 1st Bde. to advance directly to Valguarnera. This move, largely on foot, across the grain of the country was an extraordinary effort which could only have been carried out by fit and determined men. The brief struggle for the approaches to the town, together with 3rd Bde.’s actions were fought by the infantry–without significant support–as neither tanks nor carriers could follow the men across narrow gullies and mountain slopes. The battles fought on July 18 produced 145 casualties, but the road to Enna and the town of Valguarnera were in Canadian hands.

The German withdrawal to new positions based on Leonforte, Assoro and Agira was also hastened by the speed of the American advance west of Enna. Gen. Oliver Leese, who commanded the XXX British Corps including the Canadians, was later to admit that it “might have been better to have let them go to Enna on the main road and to have moved the Canadian division direct against Agira from the south.” On July 17, he obtained Montgomery’s permission to shift the boundary, allowing the Americans to seize Enna but they were still denied use of the main road north which ran through Leonforte, an objective reserved for the Canadians. Montgomery now recognized that Eighth Army did have the mobility or manpower to break the stalemate at Catania by encircling Mount Etna.

The Americans were told to take over the advance along Highway 20 from Nicosia around the north side of the great volcano, a task originally assigned to the Canadians, while XXX Corps concentrated on reducing the southwestern side of the Etna defences. A fresh British division, the 78th, was to join 1st Cdn. and 51st Highland divisions in the advance.

Simonds met with his brigadiers, including the commander of the British “Malta” Brigade which was temporarily under his control, on July 19 to co-ordinate an advance which would require extraordinary effort in difficult terrain. Today, the wide valley between the Dittaino River and the hill towns to the north is bisected by the A19 Autostrada connecting Catania to Palermo, but in 1943 the area contained little more than scattered olive groves overlooked by an impressive mountain ridge. The official historian Lieutenant-Colonel G.W.L. Nicholson described the scene as the Canadian soldiers saw it in 1943. “One of these mountain strongholds was clearly visible…. The lofty peak of Assoro protecting like a sharp tooth in the jagged skyline…. This height formed a southern projection to the main ridge, which here flattened out as a high plateau extending from Leonforte, two miles northwest of Assoro to Agira six miles to the northeast. At Regalbuto, nine miles east of Agira’s 2,700 foot cone, Highway 121, which had thus far climbed tortuously into every town and village along the main ridge, temporarily forsook the hills, dropping down by relatively easy gradients to cross the valley of the Simeto west of Adrano.”

Simonds proposed to attack on a two brigade front with 2nd Bde. committed to Leonforte and 1st Bde. to Assoro. The advance east would only begin when the enemy was forced to surrender his hold on those dominant positions.

On the afternoon of July 20, 1943, the commanding officer of the Hastings and Prince Edward Regt., Lieutenant-Colonel R.A. Sutcliffe, and his intelligence officer went forward through the RCR bridgehead across the Dittaino River to reconnoitre the approaches to Assoro. Movement on this open ground in daylight proved deadly and both men were killed. Thus began one of the most remarkable feats in all of Canadian military history–a night march to the eastern side of “La Stella” the Assoro hill followed by a climb “which no one who took part in will ever forget. The mountain was terraced and always above was a tantalizing false crest, which unfolded to another crest when one approached it. It was 40 sweating minutes before we stood on top beside the shell of a great Norman castle and realized that we had achieved complete surprise….”

Major, The Lord Tweedsmuir, son of a former governor general, who was second-in-command of the Hasty Ps and who had led the assault, gave the above description of the climb to the division historical officer and noted that the battalion had reached its objective without further losses. The next morning a company of the Royal Canadian Regt., stripped of equipment, carried rations, water and ammunition to the Hasty Ps and that night the 48th Highlanders joined the battle, clearing the western approaches to Assoro. This allowed the engineers of 1st Field Company to fill a large road crater, a move that in turn permitted the Three Rivers’ tanks to join the battle. By noon on July 22, Assoro was free of the enemy.

The story of the attack on Assoro is largely known to Canadians through books written by Farley Mowatt, especially The Regiment and his 1979 memoir And No Bird Sang. Mowat’s emphasis is on the regiment and its achievements, but Assoro also was a battle in which divisional and corps artillery, engineers and armour as well as the Hasty Ps’ sister battalions played a large role. John Marteinson and Michael McNorgan, the authors of The Royal Canadian Armoured Corps, remind us that A Squadron of the Three Rivers Regt. advanced on a “boulder-strewn cutting that seemed completely impassable to tanks” and “inched their way into positions from which the gunners could fire into enemy machine-gun posts…. The tanks neutralized the well-entrenched enemy covering the road into Assoro, enabling the Highlanders to clear the ridge and make contact with the beleaguered Hasty Ps.”

In September 2005, a large delegation of veterans, friends and serving members of the Hasty Ps returned to Sicily to place a plaque at the Norman castle on top of Assoro Mountain. David Patterson, then Director of Reserve Training at the Canadian Land Force Command and Staff College in Kingston, Ont., carried out a peaceful recce, meeting with the mayor of Assoro and the landowners to reach an agreement on recreating the cross-country march and climb. The people of Assoro joined in the commemoration, welcoming their Canadian visitors as liberators who brought an end to a battle that had left their village and the Basilica of San Leone, a national monument, largely intact.

Leonforte To Agira

While the regiment was planning its daring adventure, the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry gained control of Mount Desira Rossi, a craggy projection south of the Dittaino River. The commander of 2nd Canadian Infantry Brigade, Brigadier Chris Vokes and his battalion commanders were thus able to study the approaches to Leonforte, 2nd Brigade’s objective.

Leonforte, a town of some 13,000 is astride the main road to the north coast of Sicily. The prospect of taking it was not inviting. The Patricias’ historian described the town as “oblong in shape and a kilometre in length.” He noted it could only be entered along a “twisty switchback road which crossed a deep ravine on the southern outskirts of the built-up area. The approach to the bridge, which had been destroyed, was on a reverse curve. This gave the enemy a clear field of fire. The town itself–built on a steep hillside and extending over its crest–was so complete that nothing but plunging fire could reach its garrison. Its narrow twisty streets afforded every facility for street fighting and dispersed defence.”

Intelligence reports suggested the Germans were withdrawing to positions closer to Mount Etna–further to the east–and that Leonforte was “lightly held.” So, Vokes ordered the Seaforth Highlanders of Canada to seize the town during the night of July 20-21.

The Vancouver battalion, commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel Bert Hoffmeister, had met well-organized resistance at Valguarnera and had dealt with it by directing artillery fire on positions the enemy quickly abandoned. When the Seaforths encountered a similar situation at the ravine near Leonforte they called on their mortars and the field artillery to suppress the enemy’s fire. However, as the day wore on it was evident that the Germans held Leonforte in strength.

Vokes ordered Hoffmeister to launch a full-scale attack behind a bombardment to be fired by the entire divisional artillery. This attempt at demoralizing and disorganizing the defenders required the gunners to plot their targets from a map, a procedure known as predicted fire. Unfortunately, such area shoots were sometimes subject to error due to faulty maps, inadequate meteorological data and other variables. On this occasion at least four shells fell on the farm where the Seaforths were completing an Orders Group, killing or wounding a number of officers and men. Vokes ordered the Edmonton Regt. to take over the attack. This allowed the Seaforths time to withdraw and reorganize.

The Edmonton Regt., which became known as the Loyal Edmonton Regt. on Oct. 31, 1943, was sent forward with two Saskatoon Light Infantry medium machine-gun platoons to provide covering fire. With this support, two companies entered the ravine and scaled the far bank, working their way forward under cover of darkness. This time the preliminary barrage was well concentrated on the southern end of the town and the enemy withdrew or went to ground allowing the two lead Edmonton companies to enter the town. The left flank company was counter-attacked and withdrew in some confusion. On the right, both the lead and follow-up companies reached the centre of Leonforte before enemy tanks forced them to “break into houses and form defensive positions” until the engineers bridged the ravine, allowing the tanks of the Three Rivers Regt. to join the battle.

The battalion signallers were unable to get through and this was a common problem in the mountains of central Sicily. Lt.-Col. J.C. Jefferson recruited a young Italian, Antonio Giussepi, to serve as a runner. His job: deliver a message to brigade. Reassured that the Edmonton’s were still holding firm in the town, the commander of the 90th Anti-Tank Battery, Major G.A. Welsh managed to get two of his six-pounder anti-tank guns across the ravine where they were used to destroy a machine-gun nest and knock out a German tank that controlled an entry into the town. The engineers completed their bridge on the afternoon of July 22 and Vokes sent a “flying column” of tanks and self-propelled anti-tank guns–with a company of PPCLI on board–into the centre of Leonforte. Jefferson recalled the arrival of the lead Three Rivers Sherman tank just as an enemy tank rounded the corner approaching his headquarters. “The Canadian gunner was lightning fast on the trigger and the enemy tank exploded almost in our faces.”

The battle group, led by Captain R.C. Coleman, then went about the task of clearing the town with skill and determination. By late afternoon, the enemy had withdrawn to high ground on the edge of the built-up area and two additional PPCLI companies were committed to clearing these positions.

Col. G.W.L. Nicholson, the official historian of the campaign, notes that 21 awards for bravery were made for actions at Leonforte, including the incredible deeds performed by Private S.J. Cousins of the PPCLI. Cousins, confronted by devastating fire from two enemy machine-gun posts, “rose to his feet in full view of the enemy and carrying his Bren gun boldly charged the enemy posts” silencing both machine-guns. Cousins who was killed later that day was Mentioned in Dispatches because neither the Distinguished Conduct Medal nor the Military Medal can be awarded posthumously.

The battle for Leonforte cost the Canadians 56 men killed and 105 wounded. But it also cost the Germans a key position on their outer defensive perimeter. The road north to Troina was now clear and the 1st U.S. Division, which was pushing north from Enna, could advance with a secure flank. The Big Red One and the Red Patch Div. exchanged liaison officers and prepared to deal with Montgomery’s new plan to cease battering at Catania and concentrate on breaking the Etna defences from the west. Patton’s 45th U.S. Div. was to begin advancing along the north coast highway, while 1st U.S. and 1st Cdn. Div. operated on parallel roads in the centre of the island. The 231st British Bde., known from its earlier deployment as the Malta Bde., was placed under Canadian command.

The task assigned to Lt.-Gen. G.G. Simonds required an immediate advance to Agira and on the afternoon of July 22 he met with brigade commanders to outline his plans. The Malta Bde. was to attack from the south and seize positions on the high ground east of Agira. The 1st Cdn. Bde. was to launch an attack along a six-kilometre stretch of highway, the main road to Catania. The planning assumption was that the enemy would hold the hilltop defences around Agira. Little attention was paid to the village of Nissoria, located on low ground along the highway between two low ridges.

The Germans, an infantry battalion of the 15th Panzer Grenadier Div., supported by a few tanks and self-propelled guns, had been surprised by the “remarkable athletic accomplishments” of the “British” troops who had appeared “in our backs during the night” at Assoro. They decided to defend Agira using the reverse slopes of the two ridges at Nissoria as the first and second lines of defence. Simond’s plan to use aircraft and field and medium artillery to support 1st Bde.’s move into Agira assumed that a relatively light barrage–lifting 200 metres every two minutes–would be enough to neutralize the enemy and permit the Canadians to close and destroy.

A Royal Canadian Regt. company commander described the advance as resembling “a training picture” as “an irregular line of troops” moved forward. The “clank and whine of Shermans lifted great clouds of dust…and in the distance the artillery layed a smokey, metal pall over the hills.” The operations of war are very different from training exercises and once the barrage lifted the enemy responded quickly, inflicting casualties on the lead companies and knocking out 10 of the Three Rivers Shermans. The RCR reserve companies also reacted, swinging around to their right where they discovered a deep gully running parallel to the road. Following this route they reached a position well beyond Nissoria and halfway to Agira. They were, however, unable to establish radio contact and unwilling to advance further without orders.

Neither Brig. Howard Graham nor Simonds knew where the RCR companies were. They arranged for a deliberate attack on Nissoria by the Hasty Ps to be carried out after midnight. The battalion secured Nissoria, but the second ridge east of the village was well defended and, at dawn, German mortar fire inflicted further casualties. This engagement cost the Hasty Ps 80 killed and wounded, the heaviest single-day losses suffered by any Canadian battalion in Sicily.

Two attempts to reach Agira had failed and since Simonds had ordered the RCR companies to withdraw to avoid casualties from their own artillery it was clearly time to pause and reorganize. The 48th Highlanders of Canada were told to capture Monte di Nissoria, the peak north of the village, in preparation for a new advance by 2nd Bde. to be made on the evening of July 26. Lt.-Col. Ian Johnston sent a single company forward hoping to secure the northern end of the feature before committing the rest of his battalion. The lead company got onto its objective, but attempts to expand the foothold failed in the face of enemy fire and the Highlanders withdrew.

Simonds, under pressure from his corps and army commanders, had little choice but to press ahead. The 1st U.S. Infantry Div. was also meeting fierce resistance at Nicosia, north of Nissoria, and so a new attack was planned for July 27. From Nicosia, Highway 120 ran east along the northern edge of Mount Etna. This offered an opportunity to outflank the enemy holding up Montgomery’s advance. The Canadians and the newly arrived British 78th Div. were playing a vital supporting role and an all-out effort was required. Unfortunately, this meant that Agira would be attacked while the enemy held the northern flank.

This problem was partly overcome on the night of July 26 when a platoon from D Company of the Edmonton Regt. “travelling light but with all their platoon weapons plus extra ammunitions” walked “eight miles over volcanically torn up country” to cut the Agira-Nicosia road. They dug-in at a point where the road crosses a small ridge at the end of a switchback turn and held the position, ambushing German trucks and accounting for three tanks and a valuable tank recovery vehicle before reinforcements arrived. Lieutenant John Dougan was awarded the Military Cross for this action.

The plan for the third attempt to seize Agira recognized the enemy’s determination to hold the low ridge–code-named Lion–east of Nissoria. The Patricias advanced behind the largest artillery barrage yet fired in Sicily. The attack, supported by two squadrons of Three Rivers tanks, was a complete success. As darkness fell the reserve companies were ordered forward to capture Tiger, a low ridge 1,000 metres to the east. However, the Sicilian landscape defeated all efforts to keep up with the barrage.

Vokes went ahead with the next stage of the plan by committing the Seaforth Highlanders to attack Grizzly, the high ground on the western edge of Agira. The right flank Seaforth company discovered that the enemy had regained control of parts of Lion which they held until daybreak. On the left, A Co., commanded by Maj. H.P. Bell-Irving, bypassed the enemy reaching Tiger by first light and routing the enemy. Hoffmeister ordered his reserve companies forward to consolidate the gains and deal with the expected counter-attack.

However, the enemy was in no condition to launch a counter-attack. The only available reserve was a fresh battalion from 29 Panzer Grenadier Div. It was brought forward to take over the defence of Grizzly while the battered 104th Panzer Grenadier Regt. reorganized. The key to the Grizzly position, Monte Fronte, was strongly posted with additional machine-gun and mortars, but they failed to appreciate the determination of Bell-Irving and his men. Leaving one platoon at the base of the hill to occupy the enemy’s attention, he led the balance of the company around the right flank where terraced orchards and vineyards provided cover to the base of a 300-foot cliff which they promptly scaled. When reinforcements arrived, Bell-Irving was able to clear the rest of Monte Fronte.

Footage of General Montgomery meeting the 1st Canadian Tank Brigade, 26 July 1943. IWM AYY 512/2/5

The northern end of Grizzly was dominated by Cemetery Hill and when the Edmonton Regiment’s attack began the enemy seemed in full control. Once again success depended upon the initiative of company and platoon commanders. A section of men worked their way around the hill creating distractions that allowed the rest of the company to charge the enemy with fixed bayonets. By the morning of July 28, Grizzly was secure.

Taking no chances, Simonds arranged for full artillery support to attack Agira. The Patricias and the sorely tired citizens of the town were spared further casualties when an artillery observation officer discovered that the streets to Agira were filled with friendly people anxious to welcome the Canadians. The barrage was cancelled and the Patricia’s entered the town as liberators. They received an ovation from the population but as they climbed the steep streets into the heart of Agira they met a different kind of welcome from enemy pockets of resistance. It required two hours of fairly stiff house-to-house fighting and the employment of a third rifle company as well as assistance from a squadron of tanks to clear the town. Agira cost the Canadians 438 casualties, the costliest battle of the Sicilian campaign.

The Etna Line

One of the original reasons for mounting Operation Husky, the July 1943 invasion of Sicily, was the hope that the conquest of Italian territory would hasten the fall of Mussolini’s government. On July 25, as the Canadians fought for Agira, news that Mussolini had “resigned” was flashed around the world. King Vittorio Emanuele III assumed command of the Italian armed forces and appointed Marshal Pietro Badoglio as prime minister. Badoglio acted quickly to assure Hitler that Italy remained loyal to its Axis partner but he was in fact determined to seek an armistice with the Allies as soon as possible. The story of Mussolini’s downfall further demoralized the Italian troops in Sicily, but for the Allies and the Germans it was war as usual. Of far greater interest to the front line troops was a five-hour downpour on July 29 that provided the first rain since the landings almost three weeks before. Battalion war diaries describe the sheer bliss of open-air shower baths bringing relief from the dust and intense heat.

The rain also fell on the troops of the 3rd Canadian Infantry Brigade who had been preparing the way for the newly arrived British 78th Division. The Royal 22nd Regiment was tasked with the capture of two prominent hills controlling the approaches to the town of Catenanuova which the West Nova Scotia Regt. was to secure. Lieutenant-Colonel J.P.E. Bernatchez employed two companies in the first phase of the attack and Mount Santa Maria was taken by a bayonet charge following closely behind a heavy artillery concentration. The company on the right, advancing over the lower slopes of Mount Scalpello, was met by fire from 88-mm guns as well as the usual mortar and machine-gun fire. The enemy was too dispersed and well-hidden for the artillery to be effective and clearing the area required close work with infantry and mortars. The Van Doos had taken their objectives; now they had to hold them against strong enemy pressure.

As casualties mounted, the company on Santa Maria was withdrawn and it appeared that 3rd Bde.’s first action was failing. The enemy’s determination to crush the Van Doos had allowed the West Novas to move on Catenanuova. However, before the town could be taken, Montgomery ordered a pause in operations to prepare for a new offensive code named “Hardgate” employing the 78th Div. in addition to 1st Canadian and 51st Highland divisions.

Before examining Operation Hardgate and the final stages of the battle for Sicily it is necessary to offer a more complete description of the terrain over which the battle was fought. Serious military historians have long recognized that the ground is one of the most important “primary sources” available to researchers and this seems especially true in Sicily and Italy. The following description of the area between Agira and Mount Etna, “a jumble of ridges and hills…flat-topped or round and swelling, or sharp and precipitous” appears in the British official history and could only have been written by someone who was there in the summer of 1943.

“These heights and valleys though harsh were not bare and barren for they had been cultivated through the centuries. There were groves and belts of olive and almond and other trees and, within reach of irrigation, plantations of lemons and oranges. The hill slopes were terraced, often for vines, and cactus and prickly pear were planted as hedges and boundaries, and there were many patches of scrub. The hills were limestone and the soil was shallow, and time and weather had carved, scraped and gouged out pinnacles, battlements and cliffs, razor-backs and ravines, and had scattered boulders everywhere. In the river valleys and on any plateau there were fields strewn with stones and at this season covered with stubble or withered grass laced with weeds and prickles. The river banks made curves and loops, and fell sometimes twenty feet or more to the river beds, and gullies, pits and caves were plentiful.”

The author also noted a truth that all Canadian veterans would vouch for: “The very rugged country prevented ambitious deployments of troops who had very little pack transport or none. It was admirably suited to infantry tactics, though in the nature of things the attacker toiled up, across, perhaps down to get to grips with an enemy whom often he could not see. Allied tactics sometimes showed the plain-dweller’s tendency to underestimate the size of features, and used one battalion where two or three would have covered the ground better. The defender tucked himself in behind reverse slopes, among boulders, and in gullies, holes and caves. Ensconced, with a good view and plenty of breath, he hoped to do execution until expelled or until orders came to slip away, and he pounded off, with lungs soon bursting and temples throbbing, through another position already held behind him, to a more distant position for himself. But the fighting was far from being all tip and run; the records of bloody combats witness the contrary. Dust, heat and iron-hard ground spared nobody.”

Montgomery and his generals, including the young Canadian commander Guy Simonds, had come to recognize these basic realities by late July and the preparations for Hardgate took them into account. Alexander met with his two army commanders, Montgomery and Patton, to plan the offensive and got them to agree to a fully co-ordinated series of attacks. The American Seventh Army was to advance along the north coast to Messina while the British and Canadians tried to break through the Etna Line on the lower slopes of the famous volcano.

The Germans had begun to plan for their eventual withdrawal from Sicily but in late July there was no set timetable and Gen. Hans Hube had received substantial reinforcements. Much of the 29th Panzer Grenadier Div. crossed to the island to defend the northern approaches to Messina and the evacuation route to the mainland, allowing Hube to reduce the frontage occupied by his other divisions and to reinforce the Hermann Göring Div., facing the British and Canadians, with paratroops and fortress battalions.

The Etna Line was backed by two secondary positions the Germans could withdraw to if a breakthrough occurred, but on July 30 they were fairly confident they could hold out for some time. One unresolved question was the attitude and morale of the Italian troops, who in accordance with Badoglio’s proclamation were still supposed to serve alongside their German allies. Regiments of the Asota, Assietta and Napoli divisions were given sectors of the front to hold, but the German commanders did not really trust their partners who were almost universally anxious to end Italian participation in a war, fought on their soil, to benefit Hitler.

Operation Hardgate began on the night of July 29-30 when 3rd Canadian Bde., supported by fire from field and two medium artillery regiments, seized control of Santa Maria and Catenanuova. This sector of the front had been handed over to a German fortress battalion that according to German sources “fled in a shameful manner” allowing the West Novas to secure the town. Elsewhere, however, resistance continued throughout the day with fierce counter-attacks that had to be broken up with observed artillery fire.

The rest of 1st Canadian Div. led off the next phase of Hardgate with a carefully controlled advance from Agira to Regalbuto. This time the objective, Regalbuto, sat on a rounded hump surrounded by higher hills. The defenders from the Hermann Göring Div. included an engineer battalion fighting as infantry, elements of 3rd Parachute Regt. and a company of Mk. IV tanks. Their orders were to hold their position “at all costs” adding that previously issued instructions for withdrawal were “preparatory” and required an “express order” from division.

For the attack, Simonds decided to use the 231st (Malta) Bde. with 1st Canadian Bde. ready to pass through it. South of Highway 121, the Regalbuto Ridge led to Mount Santa Lucia, a sharp peak overlooking the town. To the north a similar hill, Mount Serione, dominated the approach. Beyond these prime defensive positions are more hills, the town itself and a deep ravine. The 231st captured and held both the western end of the ridge and Mount Serione but could go no further and Simonds committed the Canadians late on the evening of July 31.

The Royal Canadian Regt. used a barely visible cross-country track to bypass the ridge and reach the ravine at the southern edge of Regalbuto. Their objective, Tower Hill east of the town, could only be reached by descending into the gully and then climbing the other shale-covered slope. The enemy responded with murderous fire forcing the RCRs to dig in until darkness permitted a withdrawal.

The 48th Highlanders, fighting on the northern side of the town, were also heavily engaged and Simonds decided to send the reserve battalion, the Hastings and Prince Edward Regt., on a wide flanking movement designed to seize Tower Hill and the town from the rear. Such an advance was easy to accomplish on a talc-covered map board but on the ground the Hasty Ps would have to cross the ravine, capture two isolated hills and then turn north to their objective. The battalion brought their heavy three-inch mortars with them and this, together with good artillery observation from Mount San Giorgio, won the day at Tower Hill, forcing an enemy withdrawal from a town that Canadian soldiers remember as a shattered ruin largely deserted by civilians who had fled the relentless air and artillery bombardment.

Largely but not entirely deserted, Regalbuto was no sooner liberated than it was attacked by a squadron of American fighter-bombers. Correspondent Peter Stursberg of the CBC was there to witness the “scenes of horror: a hand, white and lifeless, sticking out of the rubble; a girl on top of the wreckage of her home, crying and waving her arms in despair.” However, he did not fully report the incident as the “censors thought it would be bad for morale.” The problems of target identification in Sicily had led air commanders to avoid close-support missions and concentrate on attacking the rear areas. This time, both the Desert Air Force and the Americans had struck at the German convoys withdrawing to the east. Regalbuto had been mistaken for Adrano, the next objective.

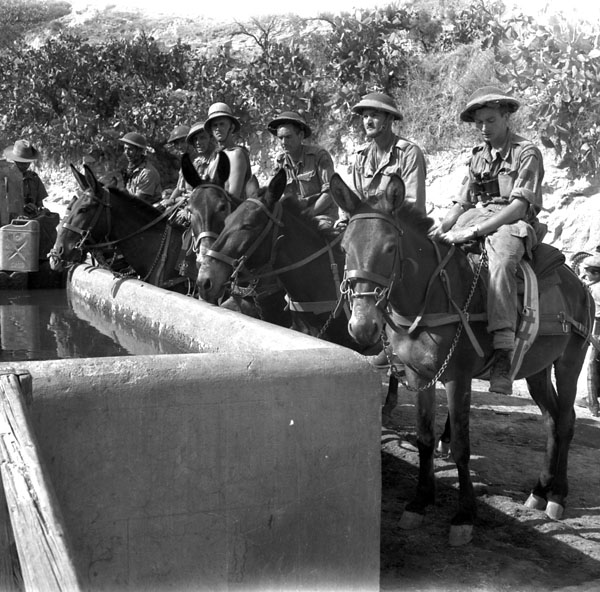

While 1st Bde. fought for Regalbuto, 2nd Bde., co-ordinating its operations with the right-flank regiment of 1st U.S. Div., had worked its way around the town towards the heights above the Troina River. The Loyal Edmonton Regt. was in the lead supported by a platoon of the Saskatoon Light Inf., who made use of mules to transport mortars and medium machine-guns. With mules, progress was slow, estimated at a mile an hour over a boulder strewn, dry river bed. The heights, especially Hill 736, proved to be occupied by the enemy and the Edmontons were forced to try and dig in under the blazing sun until the mules arrived with the three-inch mortars and radios to contact the artillery. A set-piece attack with full support forced an enemy withdrawal and the Seaforths took over the lead.

The ground east of the Troina allowed the tanks of the Three Rivers Regt. to advance with the infantry and so Simonds ordered a tank-infantry battlegroup to strike east to the Simeto River and Adrano. The tanks could provide closer, more accurate fire support than the artillery and the Seaforths became enthusiastic practitioners of combined arms tactics. Stursberg interviewed Simonds after the battle and the divisional commander singled out the engineers who built the river crossings and improved the tracks for special praise, though he insisted that “each arm and service has gone full out to do its share.”

The advance to Adrano was the last major operation carried out by the Canadians in Sicily. As the German defensive perimeter contracted, the Canadians were squeezed out of the battle and sent into reserve. The headquarters of 1st Tank Bde. and the two armoured regiments–the Calgary Regt. and the Ontario Regt. that had been supporting British units–rejoined their comrades. Unfortunately, much of the concentration area south of Catania was a notorious malaria zone and despite precautions hundreds of new cases were added to the toll mosquitoes had taken since the July 10 landings. When the 562 deaths, 1,200 wounded and several hundred battle exhaustion casualties are added to this total, one in every four Canadians who fought in Sicily was a war casualty.

Many historians have questioned the conduct of the Sicilian campaign and wondered if it was worth the costs in blood and tears. Carlo D’Este, the best known American student of the campaign, describes Sicily as a “bitter victory” because much of the German army escaped across the Straits of Messina to fight another day. He also argues that the differences between the British and Americans over strategy were aggravated by national and personality conflicts among the Allied generals that were to influence operations for the rest of the war.

A Canadian historian of the campaign, Bill McAndrew, is careful to distinguish between the military achievements of the Canadians who fought so successfully at the section, platoon, company and battalion levels and the higher command. The failure “to prevent, stop or even hinder the German evacuation of the island” was, he writes, “a combined operations debacle.” But the navy and air force both had good reasons for not committing resources to the costly task of closing the straits and the army had quite enough to do overcoming a determined enemy holding such favourable ground. Sicily was the first real test of what Canada’s citizen army could accomplish in battle and they passed with highest honours.